Brussels: Capital of Europe or Eurabia?

Brussels: Capital of Europe or Eurabia?

Giulio Meotti

- “Molenbeek would love to be forgotten, because it is the very example of the failure of the multicultural society, which remains an untouchable dogma in Belgium”. — Alain Destexhe, honorary Senator in Belgium and former Secretary General of Doctors Without Borders, Le Figaro, May 3, 2022.

- “[I]n the Brussels region as a whole only a quarter of Belgians are of Belgian origin…. Molenbeek is in fact only the tip of the iceberg of the progressive Islamization in all the major Belgian cities. Islam is increasingly visible in the public space of Molenbeek, and in the month of Ramadan almost all the shops and restaurants in the city are closed during the day. In many neighborhoods, women are no longer able to dress however they want or go out at night, and homosexuals have no right of citizenship. There are, however, hardly any voices to worry about this development, as if French-speaking Belgium, anesthetized in unison by the multicultural media, had resigned itself”. — Alain Destexhe, Le Figaro, May 3, 2022

- “Today the Muslim Brotherhood… continues its lobbying and blame games with its imaginary Trojan horse: Islamophobia”. — Assita Kanko, Belgian MEP, who fled Burkina Faso to look for freedom in Europe; Euractiv, December 20, 2021

- “The aim is clear: normalise radical Islamic codes and ways of life in order gradually to transform our Western societies instead of adapting to our European way of life. As a black woman and a secular Muslim, I know what it is to live under Islamic pressure and I know what it takes to emancipate oneself in order to finally live in dignity…. Europe must urgently pull itself together and reaffirm its commitment to its own values….” — Assita Kanko, Euractiv, December 20, 2021.

- “Where will we be in 50 years? All of Europe – inshallah – will be Muslim. So, have children!” — Brahim Laytouss, president of the Islamic Cultural Center of Belgium, dhnet.be, March 5, 2019.

- The greatest form of cultural racism in Europe today is that of EU elites who censor or support this spectacular change of civilization.

- “Of all the European capitals, Brussels is the one through which the Islamist project intends to spread to Europe. Their lobbies are powerful there, so it is much easier for Islamists to break into the system and gradually transform it”. — Djemila Benhabi, Canadian journalist, lecho.com.

- “[I]n exchange [for oil], the Saudi king asked the Belgian king Baudouin to grant Arabia a monopoly on representing Islam and appointing imams in Belgium”. The Belgian government officially recognized the Islamic religion. It was the first European country to do so. There followed the inclusion of the Islamic religion in the school curriculum. — Alain Chouet, former “number two” of the DGSE, the French counterintelligence service, from his new book: “Sept pas vers l’enfer” (“Seven Steps to Hell”).

- “Eurabia” was born in those years, the years of an energy crisis, European weakness and the great rise of Islam. Sound familiar?

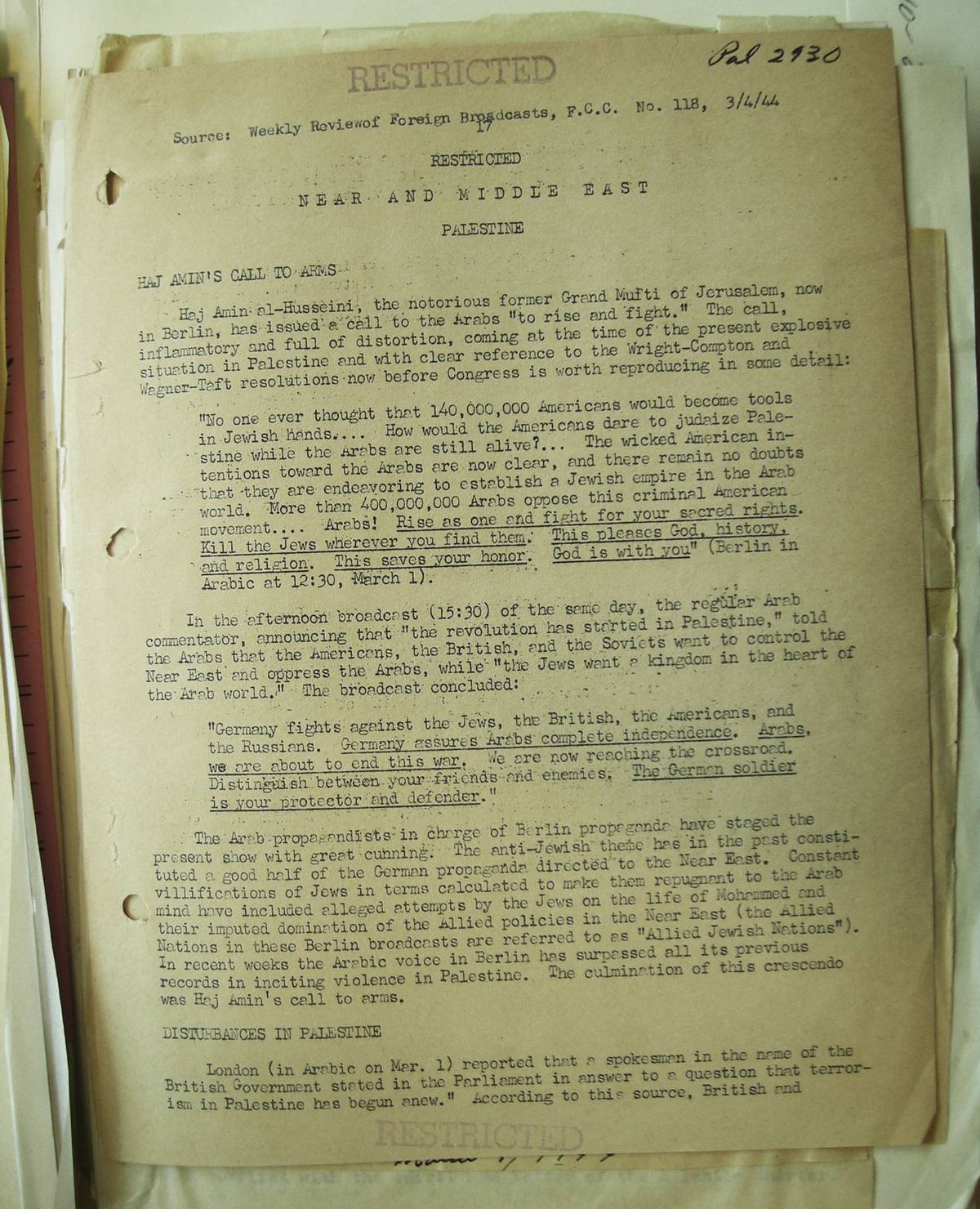

Riot police guard a road in the Molenbeek district of Brussels, after raids in which several people, including Salah Abdeslam, one of the perpetrators of the November 2015 Paris attacks, were arrested on March 18, 2016. (Photo by Carl Court/Getty Images)

Riot police guard a road in the Molenbeek district of Brussels, after raids in which several people, including Salah Abdeslam, one of the perpetrators of the November 2015 Paris attacks, were arrested on March 18, 2016. (Photo by Carl Court/Getty Images)

While Lieven Verstraete, an acclaimed Belgian journalist who hosts the program, “De Zevende Dag” (“The Seventh Day”), was recently interviewing two members of the Green Party, he raised the issue of immigration and called Brussels “the perfect example of a city whose neighborhoods are conquered one by one by newcomers”.

Newcomers? Conquered?

“How?” replied Nadia Naji, a politician of Molenbeek’s Green party.

“Well,” Verstraete, visibly uncomfortable, tried to explain, “more and more people with immigrant origins come to live there and claim their place. Do you feel Belgian in Molenbeek?”

A few hours after the broadcast, he apologized.

“In twenty years”, the French newspaper Le Figaro predicted about Brussels, “the European capital will be Muslim”.

“Almost a third of the population of Brussels already is Muslim”, stated Olivier Servais, a sociologist at the University of Louvain. “Practitioners of Islam, due to their high birth rate, should be the majority ‘in fifteen-twenty years’. Since 2001, Mohamed has been the most popular name among babies in Brussels”.

Verstraete had told the truth — but, as is said, in the time of universal deception, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

“Molenbeek would love to be forgotten, because it is the very example of the failure of the multicultural society, which remains an untouchable dogma in Belgium”, wrote Alain Destexhe, an honorary Senator in Belgium and former Secretary General of Doctors Without Borders. He was talking about the case of Conner Rousseau, president of Vooruit, the Flemish socialist party, who recently told Humo magazine, “When I drive around Molenbeek, I do not feel [as if I am] in Belgium”.

“I no longer dare to walk hand in hand with a man in Molenbeek”, Gilles Verstraeten, a gay parliamentarian, confessed.

“[I]n the Brussels region as a whole”, Destexhe noted, “only a quarter of Belgians are of Belgian origin, 39 per cent of Belgians are of foreign origin and 35 per cent are foreigners.”

“Molenbeek is in fact only the tip of the iceberg of the progressive Islamization in all the major Belgian cities. Islam is increasingly visible in the public space of Molenbeek, and in the month of Ramadan almost all the shops and restaurants in the city are closed during the day. In many neighborhoods, women are no longer able to dress however they want or go out at night, and homosexuals have no right of citizenship. There are, however, hardly any voices to worry about this development, as if French-speaking Belgium, anesthetized in unison by the multicultural media, had resigned itself”.

It is true not just Brussels. Antwerp, the country’s second-largest city, is now 25% Muslim. Another parliamentarian, Herman de Croo , revealed that 78% of Antwerp’s children aged 1-6 are foreigners.

The former Brussels Secretary of State Bianca Debaets recently said, “there are too many areas where it is difficult for women and homosexuals to walk”.

The Chief Rabbi of Brussels, Albert Guigui, was attacked by a group of Arabs. They insulted him, spat on him and kicked him. Since then, Guigui has not worn his skullcap in public.

No Jew lives in the Gare du Nord district anymore. “There are hardly any Jews left in this neighborhood,” remarked Michel Laub, founder of the Museum of Deportation in Malines. “Yet this part of Schaerbeek near the Gare du Nord was once an important Jewish quarter.”

For women, too, Brussels has become dangerous. “The Belgian political-media elites have surrendered in the face of the spread of Islamic fundamentalism”, Fadila Maaroufi, a Belgian-Moroccan social worker and founder of the Observatory of Fundamentalisms in Brussels, told the French magazine Marianne.

“I grew up in a Moroccan family in a neighborhood near Molenbeek. In the 1980s, it was still quite cosmopolitan. Then, little by little, we saw the native Belgians leaving. I witnessed the rise of Islam, my sisters veiled while my parents wore flared pants. I myself have come under pressure, including from my family. It had become inconceivable that I did not veil myself …. When I tried to alert public authorities and associations, I found myself facing a wall. There have been attacks in Paris and attacks in Brussels, yet I had the feeling that we still did not grasp the extent of the problem”.

In such an environment, freedom of expression also finds itself in dramatic retreat.

Belgian student associations protested the arrival in the capital of the publisher of satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo, “Riss”, who survived a 2015 Islamist massacre in the paper’s office.

The Filigranes bookshop in Brussels, the largest in the country, canceled a meeting with the journalist Éric Zemmour for “security reasons”.

Demonstrations against Zemmour had been planned and a group, “Collective Against Islamophobia”, had filed a complaint. The Hergé Museum took back its tribute to Charlie Hebdo by censoring itself. An exhibition that had been planned was canceled “for security reasons”.

“Today the Muslim Brotherhood, spearhead of political Islam and of the insidious soft Islamisation of Western societies, continues its lobbying and blame games with its imaginary Trojan horse: Islamophobia”, wrote a Belgian MEP, Assita Kanko, who fled Burkina Faso to look for freedom in Europe.

“The aim is clear: normalise radical Islamic codes and ways of life in order gradually to transform our Western societies instead of adapting to our European way of life. As a black woman and a secular Muslim, I know what it is to live under Islamic pressure and I know what it takes to emancipate oneself in order to finally live in dignity. The fight to preserve European civilisation is a fight to preserve humanism …. Two stones support the European temple: the Judeo-Christian heritage with the idea of human dignity and the Enlightenment, with the intellectual effervescence that accompanied it. It is from this subtle alchemy that European culture was born. European Judeo-Christian civilisation has created for itself over the centuries the conditions for its intellectual emancipation, and it can be proud of this …. Europe must urgently pull itself together and reaffirm its commitment to its own values….”

Destexhe, in his book “Immigration et Intégration: avant qu’il ne soit trop tard” (“Immigration and Integration: Before it will be too late”) , recalled that from 2000 to 2010, Belgium welcomed more than a million migrants into a population of eleven million. It was a demographic tsunami that would forever change the face of Belgian society.

“Belgium was the first to recognize and subsidize Islam; it also elected the first veiled parliamentarian”. Canadian journalist Djemal Benhabi told L’Echo,

“Of all the European capitals, Brussels is the one through which the Islamist project intends to spread to Europe. Their lobbies are powerful there, so it is much easier for Islamists to break into the system and gradually transform it”.

Journalist Marie-Cécile Royen also described the same collaboration in an article, “How the Muslim Brotherhood took Belgium hostage”.

We recently saw what the “left’s” alliance with Islam means in Brussels. Socialists and Greens just voted in the Brussels Parliament not to ban the ritual slaughter of animals. Le Monde called it the “community phenomenon”: Brussels elects representatives who benefit from the support of one community or another in this highly multicultural region and are sometimes forced to abandon some of their convictions, or a facet of their identity, in order not to alienate voters.

Djemila Benhabib, in Le Point, noted that “in Brussels half of the Socialist electorate is Muslim.” “[I]n Brussels now”, she reported, “politics is in the hands of conservative Muslims”.

As they say: It’s the demography, stupid.

According to French demographer Michéle Tribalat, in the Brussels region (1.2 million inhabitants), 57% of those under 18 are of non-European origin; in the city of Brussels 68.4% of those under 18 are of non-European origin and in Antwerp (529,000 inhabitants), 51.3% of those under 18 are of non-European origin.

De-Christianization accompanies Islamization. 36 out of 110 churches in Brussels are destined to change their use in the face of the dramatic decline of the faithful. According to an Rtbf dossier, this is the plan of the archbishop of Brussels: “Homes, museums, hotels, climbing walls… What to do with our deconsecrated churches?”

Jean-Pierre Martin and Christophe Lamfalussy in their book “Molenbeek-Sur-Djihad” disclosed that “in Molenbeek, in an area of just six square kilometers, there are 25 mosques”. What is that, if not Islamization?

Professor Felice Dassetto , in his book, “L’iris et le croissant”, wrote that with more than 200 organizations that explicitly refer to Islam, it, after football, is the most mobilizing organized reality in Brussels — more than more than political parties, more than trade unions, more than the Catholic Church. “41 percent of public school students,” noted Le Figaro, “take the Muslim religion course”.

Welcome to the “European capital .. of the Muslim Brotherhood” — and the Muslim Brotherhood know it. “Where will we be in 50 years?” the president of the Islamic Cultural Center of Belgium felt free to declare. “All of Europe – inshallah – will be Muslim. So, have children!”

The greatest form of cultural racism in Europe today is that of EU elites who censor or support this spectacular change of civilization.

Meanwhile, discussion of Islam has become a “taboo” in the European capital, Florence Bergeaud-Blackler, CNRS researcher and anthropologist, told L’Express. Certain districts of Brussels have become “a kind of sanctuary of Islam in Europe”.

The answer is in Professor Felice Dassetto’s book: in the mid-1970s there were only 6 mosques and Koranic schools in Brussels, in the early 1980s there were 38, now they are 80. And so, headlines Le Vif, “mosque projects are flourishing in Brussels”.

How did we get here?

In the midst of the 1973 oil crisis, Belgium turned to Saudi Arabia for supplies. Muslims in Belgium were of the first generation: they worked in the mines and wanted spaces to pray. Belgium’s King Baudouin, in exchange for oil supplies, offered the Saudis the Pavillon du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, along with a 99-year lease. The building stands two hundred meters from the Schuman Palace and the headquarters of the European Union. Saudi Arabia soon transformed it into the Grand Mosque of Brussels, which has since been the de facto Islamic authority of Belgium.

As Alain Chouet, the former “number two” of the DGSE, the French counterintelligence service, recounted in his newly published book “Sept pas vers l’enfer” (“Seven Steps to Hell”), “in exchange, the Saudi king asked the Belgian king Baudouin to grant Arabia a monopoly on representing Islam and appointing imams in Belgium”. The Belgian government officially recognized the Islamic religion. It was the first European country to do so. There followed the inclusion of the Islamic religion in the school curriculum.

“Eurabia” was born in those years, the years of an energy crisis, European weakness and the great rise of Islam. Sound familiar?

Giulio Meotti, Cultural Editor for Il Foglio, is an Italian journalist and author.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com

Marc Chagall Urodziny (1915), Museum of Modern Art w Nowym Jorku [Źródło: Wikipedia]

Marc Chagall Urodziny (1915), Museum of Modern Art w Nowym Jorku [Źródło: Wikipedia]