KISSINGER (Fot. Sławomir Kamiński / AG)

KISSINGER (Fot. Sławomir Kamiński / AG)

Maciej Jarkowiec

Ma 99 lat, przyjmują go wszystkie głowy państw i słuchają uważnie

.

Latem 1992 r. Henry Kissinger, były szef amerykańskiej dyplomacji, przyleciał do Petersburga. Na lotnisku czekał na niego niewysoki, sprężysty facet nazwiskiem Putin, który pracował dla mera miasta Anatolija Sobczaka jako ekspert do spraw międzynarodowych. Kissinger przybył otworzyć współpracę między zachodnim biznesem i bankami a nową rosyjską elitą. Gdy na kanapie limuzyny w drodze do hotelu Putin wyznał, że był agentem KGB, Kissinger odpowiedział: – Wszyscy porządni ludzie zaczynali w wywiadzie. Ja też.

Później powiedział coś, co jego rozmówca uznał za „kompletnie niespodziewane i bardzo interesujące”: – Wie pan, w Stanach krytykują mnie za stanowisko, jakie przed kilkoma laty przyjąłem wobec ZSRR. Uważałem, że Związek Radziecki nie powinien wycofywać się z Europy Wschodniej. Zmienialiśmy równowagę światową w zawrotnym tempie i twierdziłem, że przyniesie to niekorzystne konsekwencje. (…) Szczerze panu powiem, do dziś nie rozumiem, dlaczego Gorbaczow do tego dopuścił.

Kilka lat później Putin napisze: „Kissinger miał rację. Uniknęlibyśmy wielu problemów, gdybyśmy tak pośpiesznie nie ewakuowali się z Europy Wschodniej”.

Ukraińskie lenno

Kissinger ma dziś 99 lat. Pozostaje czynnym macherem geopolityki, konsultantem konsorcjów międzynarodowych, dyplomatów i rządów państw. Nie ma na świecie drugiego człowieka, który od końca lat 50. ubiegłego wieku ma nieprzerwanie dostęp do gabinetów najważniejszych światowych przywódców. Z jego doradztwa korzystali wszyscy amerykańscy prezydenci od Eisenhowera do Trumpa. Słowa, które wypowiada Kissinger – prywatnie lub publicznie – mają moc wpływania na najważniejsze geopolityczne procesy. Przed kilkoma tygodniami na światowym forum ekonomicznym w Davos Kissinger powiedział, że aby zakończyć wojnę, Ukraina powinna oddać część swojego terytorium Rosji. Zachód – według Kissingera – musi ją do tego nakłonić.

Wywołało to oburzenie. „Kyiv Post” skomentował je, przytaczając słowa urodzonej w Kijowie legendarnej premier Izraela Goldy Meir: „My, Izrael, chcemy pozostać przy życiu. Nasi sąsiedzi pragną, abyśmy byli martwi. W takich warunkach nie ma wielkiego pola do kompromisu”. Oddanie części terytorium Rosji – pisali ukraińscy komentatorzy – to jak zaproszenie mordercy, który napadł na twój dom, aby zaopiekował się dziećmi, bo obiecał, że będzie grzeczny.

Emocje Ukraińców podziela wielu – w Polsce, w krajach bałtyckich, również w USA i w innych miejscach – ale prawda jest taka, że Kissinger nie jest jedynym prominentnym zwolennikiem polityki appeasementu wobec Moskwy. Podobny sentyment, lecz w mniej dobitnych słowach, wyraża m.in. prezydent Francji Emmanuel Macron, wielu polityków w Niemczech czy we Włoszech, a w USA choćby „New York Times”, który w komentarzu redakcyjnym z 19 maja napisał, że liderzy ukraińscy będą musieli podjąć „bolesne decyzje terytorialne, jakich wymaga każdy kompromis”.

Zwolennicy takiego poglądu uważają się za przedstawicieli geopolitycznego realizmu, którego Henry Kissinger od wielu dekad pozostaje najwyższym kapłanem.

Narodowy nadinteres

Czym jest realizm w stosunkach międzynarodowych? Ten sam „New York Times”, krytykując Kissingera w latach 70., pisał, że nie jest niczym innym tylko „obsesją na punkcie siły i międzynarodowego porządku kosztem ludzkiego życia”. Podręcznikowym przykładem jest rozkaz Winstona Churchilla z czerwca 1940 r. zatopienia francuskich okrętów wojennych, w wyniku czego zginęło 1300 sprzymierzonych z Wielką Brytanią Francuzów. Celem nadrzędnym było, aby jednostki nie zostały przejęte przez marynarkę Niemiec.

Ojcem nowoczesnego realizmu jest Hans Morgenthau (1904-1980), amerykański badacz niemieckiego pochodzenia, który we wczesnej fazie kariery Kissingera był jego przyjacielem i mentorem. Według Morgenthaua interes narodowy należy definiować wąsko – jako przeciwdziałanie czynnikom zewnętrznym i ekonomicznym zagrażającym bezpieczeństwu państwa. Żadna idea – jak szerzenie demokracji czy przestrzeganie praw człowieka – nie może przeszkadzać w realizacji interesu narodowego. Imperatyw moralny nie może dyktować decyzji. Centralne jest pojęcie siły – kraj buduje ją, aby skutecznie zabiegać o swój interes. Składnikiem siły według Morgenthaua jest reputacja. Wojny prowadzone przez realistów są mniej zabójcze i niszczące, bo jasno definiują cel i dążą do jego szybkiego osiągnięcia. Wojny toczone w oparciu o idee niechybnie prowadzą do rzezi i trwają długo. W ujęciu Morgenthaua wojną idealistów była agresja hitlerowska, ale również zaangażowanie USA w Azji. W latach 60. Morgenthau był doradcą w administracji Lyndona Johnsona.

Publicznie krytykował amerykańską interwencję w Wietnamie, uznając ją za idealistyczną, zagrażającą pozycji państwa i obniżającą reputację USA. Został zwolniony. W tym momencie drogi Morgenthaua i Kissingera się rozeszły.

Mała wojna atomowa

Heinz Kissinger urodził się w 1923 r. w bawarskim Fürth, w rodzinie żydowskiej. W dzieciństwie był wielokrotnie napadany i bity przez grupy Hitlerjugend. Kissingerowie uciekli do USA w 1938 r. Zamieszkali w niemiecko-żydowskiej dzielnicy na Górnym Manhattanie. Heinz został Henrym, pracował w fabryce pędzli i planował zostać księgowym. „Nigdy nie zapomnę emocji, jakie towarzyszyły mi, gdy pierwszy raz wyszedłem na ulice Nowego Jorku. Ujrzałem nadchodzącą grupę chłopców i chciałem przejść na drugą stronę jezdni, żeby nie zostać pobitym. Wtedy przypomniałem sobie, gdzie jestem”. Ameryka była jego wyzwoleniem. Choć Kissinger nigdy do końca nie pozbył się niemieckiego akcentu, przyjaciel z lat młodości powiedział o nim: „Był bardziej amerykański od najbardziej amerykańskich Amerykanów”.

Do Niemiec wrócił jako 20-letni żołnierz amerykańskiej armii, brał udział w wyzwoleniu obozu koncentracyjnego w Ahlem pod Hanowerem. Po wojnie skorzystał z ustawy stypendialnej dla weteranów i dostał się na Harvard. Tam poznał ojca szkoły realistów Hansa Morgenthaua. Na początku lat 50., jeszcze jako student, zorganizował seminarium z polityki międzynarodowej, na które, dzięki wysokim grantom z prywatnych fundacji (jak się później okazało, w dużym stopniu finansowanych przez CIA), udało mu się ściągnąć gwiazdy. Stawili się ministrowie spraw zagranicznych, dyplomaci i politycy z całego świata, choćby późniejszy premier Kanady Pierre Trudeau czy przyszły prezydent Francji Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. Przy okazji konferencji Kissinger zgłosił się do FBI z ofertą raportowania na temat swoich gości. Prawdopodobnie ten epizod będzie miał na myśli, kiedy wiele lat później zwierzy się Putinowi, że też zaczynał jako agent.

W następnych latach kontakty zawiązane na seminarium otwierały młodemu akademikowi kolejne drzwi. Pod koniec lat 50. z jego analiz – jako profesora Harvardu – korzysta już administracja Dwighta Eisenhowera. Kissinger jest wówczas adwokatem koncepcji ograniczonej wojny atomowej. Twierdzi, że obowiązująca doktryna – zmasowanego kontrataku nuklearnego w przypadku agresji Sowietów na USA bądź ich sojuszników – jest droga i ryzykowna. Co najgorsze, nierealistyczna: w praktyce żaden prezydent nie zdecydowałby się na taki kontratak – bo oznaczałby on zagładę ludzkości – co prowadzi do wniosku, że agresja ZSRR pozostałaby bezkarna. Kissinger proponuje budować zdolność bojową użycia niewielkich, „zniechęcających” ładunków jądrowych w każdej chwili i w każdym miejscu świata, tak jak uczyniono to w Hiroszimie i Nagasaki. Taka taktyka miałaby szansę skutecznie odstraszyć wroga. Jego teoria nigdy nie została wprowadzona w życie, ale uczyniła z niego gwiazdę.

Naloty dywanowe

26 grudnia 1972 r. na Kham Thien, tętniącą życiem arterię w środku Hanoi, spadło kilkaset bomb zrzuconych z amerykańskich bombowców dalekiego zasięgu B52. Zrównanych z ziemią zostało ponad dwa tysiące domów, zginęło 280 cywilów, w tym 55 dzieci. Korespondenci opisywali odgrzebywanie ciał spod ruin, kwiczenie rannych świń i szloch kobiety: „Synku, gdzie jesteś? Amerykanie, dlaczego jesteście tak nikczemni?”. Kilka dni wcześniej amerykańskie bombowce zniszczyły szpital na przedmieściach, zabijając 28 pielęgniarek i lekarzy (pacjentów zdążono ewakuować). Kampania nalotów dywanowych na przełomie 1972 i 1973 r. trwała 12 dni i nocy.

Była częścią strategii Henry’ego Kissingera, doradcy ds. bezpieczeństwa narodowego w administracji Richarda Nixona, który chciał siłą zmusić Północ do ustępstw w toczących się negocjacjach pokojowych.

Łącznie w największej tego typu operacji od czasów drugiej wojny światowej zginęło co najmniej 1600 cywilów. Zapisy rozmów Nixona z Kissingerem (prezydent i jego doradca nagrywali się nawzajem, nie wiedząc o tym) pokazują, że uznali oni kampanię za sukces. Dzień po zbombardowaniu Kham Thien Kissinger zadzwonił do Nixona.

– Mamy ich na kolanach – powiedział.

Ale negocjatorzy z Północy nie zamierzali klękać. Warunki pokoju podpisanego kilka tygodni później w Paryżu nie różniły się od tych wynegocjowanych przed nalotami. Jeden z młodych amerykańskich dyplomatów, John Negroponte, skomentował z goryczą: „Zbombardowaliśmy ich, żeby zaakceptowali nasze ustępstwa”. Wkrótce amerykańskie wojska wyszły z kraju, a rozejm zaczął być łamany przez obie strony i wojna między Północą a Południem trwała dalej, już bez udziału USA. Jesienią Kissinger i jego wietnamski odpowiednik Le Duc Tho otrzymali pokojowego Nobla. Dwóch członków Akademii Noblowskiej w proteście odeszło z instytucji. Le Duc Tho nie przyjął wyróżnienia. Gdy Północ podbiła Sajgon, komunistyczny generał przyjmujący kapitulację Południa powiedział: „Nie macie się czego obawiać. Pośród Wietnamczyków nie ma zwycięzców i pokonanych. Przegrali tylko Amerykanie”.

Ludzkie pola szachowe

Protesty, jakie wywołało przyznanie Nobla Kissingerowi, nie brały się tylko z jego roli w bombardowaniu cywilnych celów w Wietnamie. W 1969 r. Nixon i Kissinger zdecydowali o rozpoczęciu nalotów dywanowych na Kambodżę, której Wietkong używał jako bazy wypadowej i szkoleniowej. Rozkaz, jaki Kissinger przekazał wiceszefowi sztabu generałowi Alexandrowi Haigowi, brzmiał: „[Uderzamy] wszystkim, co lata, we wszystko, co się rusza”. Amerykanie zrzucili tam więcej bomb niż w całej kampanii na Pacyfiku podczas drugiej wojny. Niektóre źródła szacują liczbę ofiar cywilnych na 100 tys. Rolnicze połacie kraju zostały zdewastowane. Na pogorzelisku marsz ku władzy rozpoczął Pol Pot. Stanley Hoffmann, kolega Kissingera z Harvardu, ocenił, że amerykańskie zbrodnie przygotowały grunt pod wzlot potwornego reżimu Czerwonych Khmerów.

W tym samym czasie po drugiej stronie kuli ziemskiej Nixon i Kissinger zaprojektowali obalenie socjalistycznego przywódcy Chile Salvadora Allende i zainstalowanie junty generała Augusto Pinocheta. Dokumenty z tajnych narad w Białym Domu pokazują, że Amerykanie obawiali się powodzenia rządów Allende i ich oddziaływania na inne kraje regionu, więc z pomocą służb prowadzili metodyczne działania sabotujące jego władzę, a później doprowadzili do jej upadku. Kissinger tak streścił sytuację: „Nie widzę powodu, dla którego mamy stać i patrzeć, jak jakiś kraj skręca w stronę komunizmu przez brak odpowiedzialności swojego społeczeństwa”. To wtedy właśnie „New York Times” krytykował jego realizm. Doktrynę Kissingera dziennik przyrównał do doktryny Breżniewa – który nie mógł przyglądać się, jak Czechosłowacja skręca w stronę Zachodu.

Tak jak dla Breżniewa Czechosłowacja, tak dla realisty Kissingera Kambodża, Chile i ludzie żyjący w tych krajach byli jedynie polami na wielkiej szachownicy, na której dziejowe partie rozgrywają mocarstwa. Dziś podobnie postrzega Ukrainę.

Nowa Jałta

Za największe sukcesy Kissingera uważa się jego działania dyplomatyczne wobec Chin i ZSRR. To on przygotował historyczną, siedmiodniową wizytę Nixona w Chinach z lutego 1972 r., która zapoczątkowała nawiązanie relacji między oboma krajami. Niewiele później, w kwietniu 1972 r., Kissinger poleciał do Moskwy w ramach realizowanej od miesięcy strategii odprężenia w stosunkach z ZSRR. Wysiłki amerykańskiej dyplomacji – którą Kissinger nieformalnie kierował przez lata za plecami sekretarza stanu, a oficjalnie jako jej szef od września 1973 – doprowadziły do podpisania pierwszych porozumień o ograniczeniu zbrojeń między USA a ZSRR (układ SALT). Zapoczątkowany przez Nixona i Kissingera ożywiony dialog między mocarstwami trwał do sowieckiej inwazji na Afganistan w 1979 r.

Dekadę później w obliczu widocznej już gołym okiem ekonomiczno-politycznej zapaści w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej Kissinger postulował zwrot w relacjach z ZSRR i dogadanie z Moskwą faktycznego, nowego podziału kontynentu. 29 stycznia 1989 r. na tajnym spotkaniu w Białym Domu między prezydentem George’em Bushem seniorem, sekretarzem stanu Jamesem Bakerem a występującym w roli nieoficjalnego doradcy Kissingerem ten ostatni nakreślił wizję historycznego układu między USA a ZSRR. Zakładał on redukcję arsenałów po obu stronach i gwarancje nieagresji. Sowieci mieliby pozwolić na ograniczone reformy w krajach satelickich, jednocześnie zachowując nad nimi kontrolę. W zamian dostaliby przyrzeczenie, że NATO nie przesunie się ani o centymetr na wschód. Wizja opierała się na zasadniczej dla doktrynerów realizmu koncepcji stref wpływu najsilniejszych państw. Aby zagwarantować nowy globalny porządek, Kissinger chciał klarownego potwierdzenia ich granic.

„Washington Post” dostał przeciek o spotkaniu. Komentatorzy pisali o drugiej Jałcie. Zwracano uwagę, że były szef dyplomacji chce oddać Rosjanom wpływy, o które się nawet nie upominają, a reformy w bloku wschodnim i jego desowietyzacja wydają się kwestią najbliższej przyszłości, bez konieczności ustępstw ze strony USA.

Kilka lat później, gdy Związek Radziecki już nie istniał, a kraje naszego regionu domagały się przyjęcia do NATO, w USA toczyła się zażarta dyskusja o rozszerzeniu paktu. Obie strony używały argumentów z arsenału geopolitycznego realizmu. Jedni realiści mówili: biorąc pod uwagę logikę dziejów, rozmiar Rosji, jej historię i położenie geograficzne, należy zakładać, że prędzej czy później znów będzie chciała poszerzyć swoją strefę wpływu. Należy więc zawczasu, wykorzystując jej chwilową słabość, przesunąć granicę konfrontacji na wschód. Drudzy realiści odpowiadali: Europa Środkowo-Wschodnia nie potrzebuje NATO, bo gwarancje bezpieczeństwa dają jej inne układy międzynarodowe. Trzeba wykorzystać ją jako pomost do budowania trwałego pokoju z Moskwą, a nie – przesuwając sojusz na wschód – zniechęcać nowe rosyjskie elity do Zachodu.

Kissinger – przynajmniej oficjalnie – zrewidował swoją pozycję z końcówki lat 80. i popierał rozszerzenie.

Upokorzenie

Dziś dyskusja wraca. Wedle zwolenników appeasementu powiększenie NATO było błędem, który uruchomił długofalowe procesy, jakie dziś doprowadziły do nowej wojny. Przypomina się przestrogi z lat 90. byłego ambasadora w Moskwie George’a Kennana, uważanego za najwybitniejszego eksperta od Rosji, jakiego Ameryka miała w XX wieku. „[Rozszerzenie NATO] jest dowodem na małe zrozumienie historii Rosji. Oczywiste jest, że jej reakcja będzie negatywna. A wtedy zwolennicy ekspansji NATO powiedzą: o proszę, ci Rosjanie zawsze są tacy sami” – mówił Kennan. Rozszerzenie nazwał najbardziej niebezpieczną decyzją, jaką USA podjęły od końca drugiej wojny światowej.

Thomas Friedman pisze w „New York Timesie”, że Ameryka jest współodpowiedzialna za pożar, jaki pogrąża Ukrainę. Przypomina, że przyjmowaniu nowych członków do NATO sprzeciwiał się sekretarz obrony w administracji Billa Clintona Bill Perry. W 2016 r. Perry wspominał: „Pracowaliśmy wtedy z Rosjanami, kiełkowała wspólna strategia długofalowej przyjaźni. Apelowali, aby tego nie psuć, przybliżając NATO do ich granic”.

Wielu komentatorów przyrównuje Rosję lat 90. do Republiki Weimarskiej. Związek Radziecki się rozpadł, Moskwa poniosła historyczną klęskę. Ale zwycięzcy popełnili błąd – tak jak w stosunku do przegranych Niemiec po pierwszej wojnie. Zamiast pomóc Rosji, upokorzyli ją.

Takie interpretacje zakładają, że gdyby nie rozszerzenie NATO, Rosja byłaby dziś demokratyczna, nowoczesna i pokojowo nastawiona do sąsiadów. Ich autorzy nie podają żadnych argumentów odwołujących się do wewnętrznej polityki Rosji, które pozwalają wyobrazić sobie, że tak w istocie by się stało. Pomijają też milczeniem emocje, jakie zdecydowały o rozszerzeniu. NATO nie dokonało ekspansji na wschód, lecz to my, społeczeństwa z tej części Europy, potężnym wysiłkiem dyplomatycznym i cywilizacyjnym wepchnęliśmy się do sojuszu. Historia i instynkt podpowiadały nam, że rację ma raczej Peter Rodman, doradca Reagana i jeden z amerykańskich zwolenników rozszerzenia, który nazywał Rosję „nieuchronną siłą natury”.

Podobnie dziś – oddanie części kraju za pokój jest wbrew instynktowi narodu Ukrainy.

Lobbysta Putina?

Realizm czy idealizm w stosunkach międzynarodowych to koncepty czysto teoretyczne. W praktyce decyduje masa czynników spoza akademickiego słownika. Spójrzmy na samego Kissingera. O tym, jak się dziś wypowiada, mogą – owszem – decydować jego naukowe poglądy. Ale czy bez znaczenia jest, że przyjaźni się z Putinem? Że przyznaje się do fascynacji Rosją? Że ma tam rozliczne kontakty? A jeśli Kissinger po prostu pracuje dla Putina – na co wskazują poszlaki – nadal można mówić, że jest geopolitycznym realistą?

Od 1982 r. były sekretarz stanu jest właścicielem firmy Kissinger Associates zajmującej się dostarczaniem usług z zakresu geopolitycznego konsultingu. Jej klienci w zdecydowanej większości pozostają nieznani, najpewniej najbardziej wrażliwe kontrakty zostają zawarte tylko w formie ustnej. Z nielicznych przecieków wiadomo, że z usług firmy korzystają korporacje i rządy. Wiadomo, że od początku lat 90. Kissinger kilkanaście razy spotykał się z Putinem. Gdy doradzał w sprawie Rosji prezydentowi Bushowi juniorowi, Putin zaatakował w Gruzji (2008), gdy doradzał Obamie, Putin zaatakował na Ukrainie (2014). Kissinger spotykał się z też z Trumpem i przyklasnął objęciu Departamentu Stanu przez dobrego znajomego Putina Rexa Tillersona.

W 2013 r. Kissinger otrzymał tytuł honoris causa Akademii Dyplomatycznej MSZ Federacji Rosyjskiej. Laudację wygłosił Putin. „Był pan w stosunku do mnie nader hojny, poświęcając mi tyle czasu, aby tłumaczyć mi wasz punkt widzenia” – powiedział.

Dzisiejszy punkt widzenia USA można by nazwać idealistycznym. Prezydent Joe Biden i sekretarz stanu Antony Blinken przy wielu okazjach definiowali konflikt jako starcie demokracji z autorytaryzmem. Praktyka pozostaje realistyczna: dajemy Ukrainie broń i wsparcie, wzmacniamy NATO, ale nie wysyłamy żołnierzy za granicę sojuszu. Uniknięcie bezpośredniej konfrontacji z Rosją pozostaje dla USA kwestią egzystencjalną.

Nie da się przewidzieć, jak będzie wyglądała polityka Waszyngtonu względem Kijowa i Moskwy w nadchodzących miesiącach i latach. Zdecydują o tym liczne czynniki, również wewnętrzne – takie jak rozkład sił na Kapitolu po wyborach czy nastawienie amerykańskiej opinii publicznej. Nie bez wpływu będą działania lobbystów. Takich jak Henry Kissinger.

Wykopaliska archeologiczne w miejscu dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie

Wykopaliska archeologiczne w miejscu dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie Spalony księgozbiór z warszawskiego getta. Co znaleźli archeolodzy na Muranowie?

Spalony księgozbiór z warszawskiego getta. Co znaleźli archeolodzy na Muranowie? Tak wygląda spalona książka znaleziona przez archeologów w piwnicach nieistniejącej dziś kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie

Tak wygląda spalona książka znaleziona przez archeologów w piwnicach nieistniejącej dziś kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie  Wykopaliska archeologiczne w miejscu dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie

Wykopaliska archeologiczne w miejscu dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie  Kubek wykopany przez archeologów w piwnicach dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie.

Kubek wykopany przez archeologów w piwnicach dawnej kamienicy przy ul. Miłej 18 / Muranowskiej 39 na Muranowie.

ELEANOR SHAKESPEARE

ELEANOR SHAKESPEARE

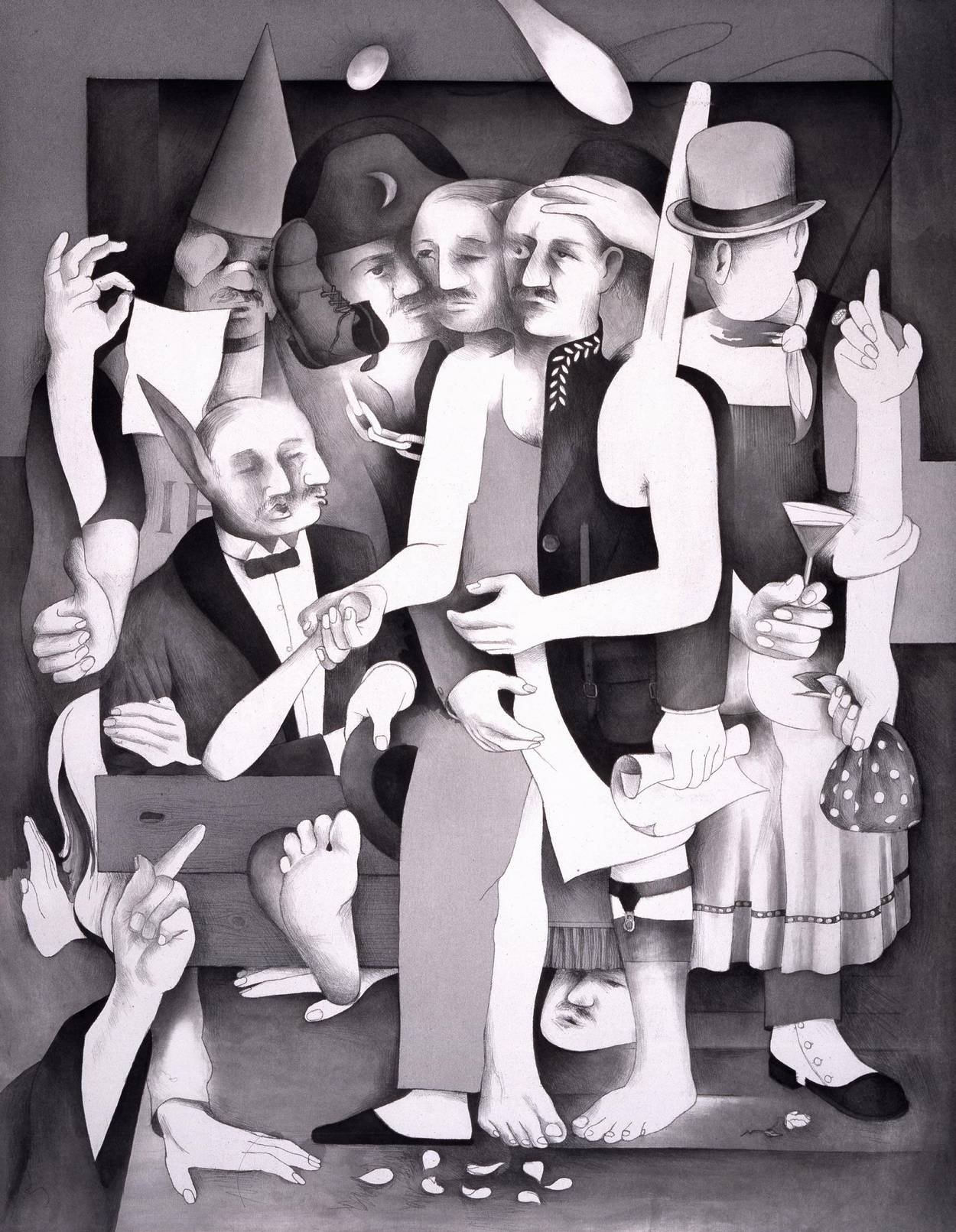

Richard Hamilton, ‘The Transmogrifications of Bloom,’ 1985, printed by Aldo Crommelynck© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

Richard Hamilton, ‘The Transmogrifications of Bloom,’ 1985, printed by Aldo Crommelynck© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM