Kto tańczy pod murem? O nowej wystawie czasowej „Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman”

Kto tańczy pod murem? O nowej wystawie czasowej „Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman”

Przemysław Batorski

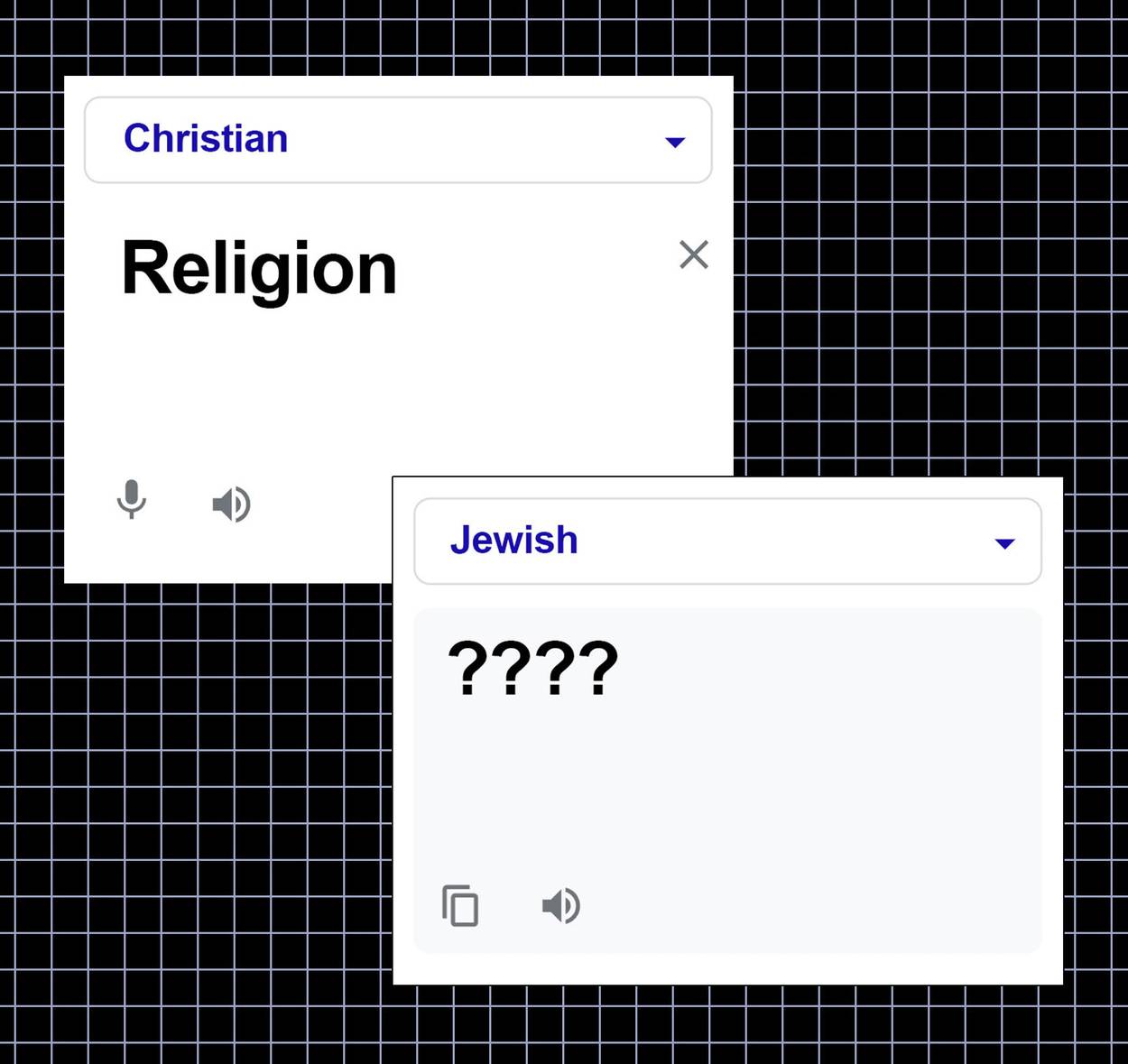

Tancerze i tancerki, aktorzy i aktorki, akrobaci i akrobatki. „Odmieńcy, którzy w tanecznych pozycjach lub w cyrkowych sztuczkach coś zakrywają i coś odkrywają, przyjmują i zmieniają role, odtwarzają kroki samotnie i poprzez taniec wchodzą w interakcję z tłumem”. Od 27 maja 2022 mogą Państwo odwiedzać w ŻIH nową wystawę czasową „Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman”, poświęconą wyjątkowemu cyklowi grafik z okresu okupacji. Kim był Mieczysław Wejman? Co o doświadczeniu wojny i losach Żydów w Warszawie mówią jego prace?

Mieczysław Wejman, Szkic do Tańczący [XI], zbiory prywatne

Mieczysław Wejman, Szkic do Tańczący [XI], zbiory prywatne

„Wyraziście rysuje się również podział na obserwowanych i obserwujących, na aktorów/tańczących/akrobatów i niechętnych im widzów, na scenę i widownię. Niektóre z przedstawionych postaci to uniwersalne typy ludzkie, groteskowe odbicie społeczeństwa jak w komedii dell’arte, na przykład powracająca w różnych ujęciach – u Wejmana uwspółcześniona, przystosowana do okupacyjnych realiów – postać Arlekina czy Kolombiny” – dodaje Luiza Nader.

Prezentowane na wystawie czasowej w Żydowskim Instytucie Historycznym im. Emanuela Ringelbluma prace Mieczysława Wejmana, malarza i grafika, znanego m.in. z cyklu Rowerzysta, powstały w okupowanej Warszawie na przełomie 1943 i 1944 r. Przez lata Tańczący interpretowani byli jako uniwersalna opowieść o wojennej apokalipsie, jednak bardziej drobiazgowa analiza, odkrywająca unikalny kontekst powstania dzieł, pozwala powiązać grafiki z historią okupowanej Warszawy, żydowskich mieszkańców getta i ofiar powstania z wiosny 1943 r.

Co cykl Wejmana mówi nam o doświadczeniu okupacji w Warszawie? O obserwowanych i obserwujących, o zabawie i śmierci?

![wejman_MN_1_comp.jpg [491.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/50fff1f345f0213782d86724d780c6de/jpg/jhi/preview/wejman_MN_1_comp.jpg) Mieczysław Wejman, Tańczący I, zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie

Mieczysław Wejman, Tańczący I, zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie

Kim był Mieczysław Wejman?

Mieczysław Wejman urodził się w 1912 r. w Brdowie niedaleko Koła w Wielkopolsce. Studiował na Wydziale Humanistycznym Uniwersytetu w Poznaniu oraz w Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie. Od 1937 r. mieszkał w Warszawie, pobierając dalsze nauki w stołecznej ASP.

Podczas okupacji mieszkał wraz z żoną Marią i synkiem Krzysztofem na Żoliborzu, przy ul. Promyka. Pracował fizycznie jako magazynier w fabryce wódek i likierów „Jamasch” pod zarządem niemieckim, kontynuował studia artystyczne i wystawiał swoje prace na konspiracyjnych pokazach. Krótko przed wybuchem powstania warszawskiego Wejmanowie, którzy spodziewali się drugiego dziecka, przenieśli się do podwarszawskiego Izabelina, a po powstaniu przedostali się do Krakowa.

Po 1945 r. Wejman stał się uznanym artystą, a także organizatorem życia i szkolnictwa artystycznego. Należał do grupy „9 grafików”, w latach 1964-1970 stworzył najważniejszy w swojej karierze cykl Rowerzysta. Przez ponad 30 lat był profesorem malarstwa i grafiki na ASP w Krakowie, sprawował też funkcję rektora tej uczelni oraz dyrektora krakowskiej Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Sztuk Plastycznych. Zmarł w Krakowie w 1997 r.

W jakich okolicznościach powstał cykl „Tańczący”?

„Wejman podczas wojny wykonał ponad sto prac: rysunków, obrazów, grafik, większość z nich zaginęła lub została zniszczona. Zachowane dzieła zazwyczaj skupiają się na portretowaniu członków rodziny, kilka z nich to pejzaże, a także niezwykle interesujące charakterystyki niemal wszystkich klas społecznych, odnoszące się do sytuacji zagrożenia, konspiracji, strachu, ukrycia czy stłoczenia na niewielkiej powierzchni” – pisze Nader.

Na początku 1944 r. Wejman przez kilka tygodni lub kilka miesięcy ukrywał się na strychu niedaleko swojego żoliborskiego mieszkania. Przyczyną był ostry konflikt z przełożonym w pracy, volksdeutschem, a także to, że brat jego żony, Stanisław Bełżyński, dowódca Kedywu Obwodu „Niwa” Armii Krajowej, był poszukiwany przez gestapo. Chociaż o działalności konspiracyjnej Wejmana wiemy niewiele, artysta nie mógł czuć się bezpiecznie. W 1943 r. Niemcy zamordowali w ruinach getta profesora Mieczysława Kotarbińskiego, u którego Wejman pobierał nauki w ASP. Z kolei Bełżyński zginął z rąk Niemców w maju 1944 r. „Duszna atmosfera konspiracji, szmalcownictwa, szemranych sytuacji i postaci silnie odcisnęła się na twórczości z tego okresu”.

![Wejman_Tańczący III (V) akwa_comp.jpg [496.26 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/0d05f91b38ccb9f3ba278d388855c95e/jpg/jhi/preview/Wejman_Ta%C5%84cz%C4%85cy%20III%20(V)%20akwa_comp.jpg) Mieczysław Wejman, Tańczący III [tu z numeracją V]

Mieczysław Wejman, Tańczący III [tu z numeracją V]

Najprawdopodobniej wtedy – podczas ukrywania się – Wejman stworzył cykl Tańczący, z którego zachowała się tylko część prac oraz kilka metalowych płyt służących do wykonywania odbitek. Tańczący to grafiki wykonane w technice akwatinty i akwaforty.

Dla Wejmana były to wówczas pierwsze próby nowego, wymagającego, a zarazem kulturowo znaczącego (m.in. przez odniesienie do głęboko krytycznych dzieł Goyi) języka wizualnego. Tańczący stają się ekranem wyświetlania, jak i konfrontacji obrazów, wydarzeń, doświadczeń i obserwacji dotyczących podzielonego miasta Warszawy i „dzielnicy zamkniętej” – warszawskiego getta.

– podaje Nader.

Firma „Jamasch”, dla której pracował Wejman, miała przed wojną żydowskich właścicieli, a jej siedziba, rozlewnia i hurtownia znajdowały się odpowiednio pod adresami Pawia 49a, Pawia 66 i Rymarska 7 (obecnie Plac Bankowy). Wszystkie te miejsca znalazły się na terenie getta, w pobliżu jego granic. „By dostać się do budynków firmy «Jamasch», Wejman mieszkający na Żoliborzu przy ul. Promyka, musiałby mur i dzielnicę żydowską mieć w zasięgu wzroku niemal bezustannie, bez względu na to, czy byłby to rok 1941, 1942, czy nawet 1943” – pisze kurator wystawy Piotr Rypson i dodaje:

Ludzie spadający na ziemię, wyskakujący z okien płonących domów, to jeden z najsilniej zapadających w pamięć obrazów z okresu powstania w getcie i ostatecznej likwidacji dzielnicy żydowskiej w Warszawie w 1943 roku, znany z kilku relacji a także precyzyjnie dokumentowanych przez niemieckiego fotografa, częściowo zamieszczonych w raporcie SS-Brigadeführera Jürgena Stroopa.

![powstanie_getto_plonie_jhi.jpg [259.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/b476f932363a8ac64f37975ba8b6660a/jpg/jhi/preview/powstanie_getto_plonie_jhi.jpg) Powstanie w getcie warszawskim. Płonąca kamienica. Zbiory ŻIH

Powstanie w getcie warszawskim. Płonąca kamienica. Zbiory ŻIH

Okrucieństwa wojny

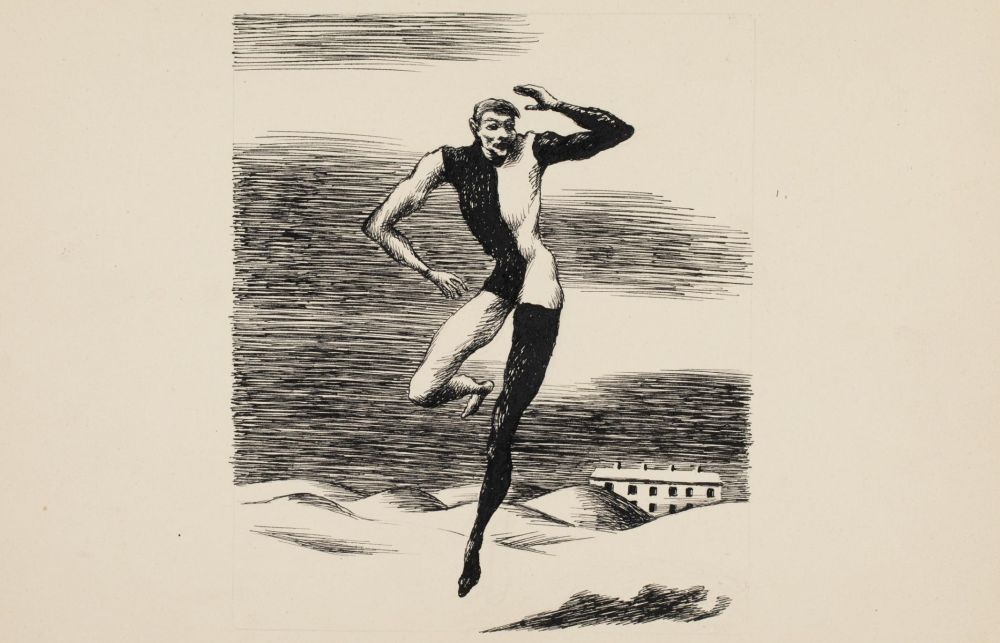

„Prace artysty pełne są zagadek, trudnych lub niemożliwych do rozwiązania rebusów, metaforycznych labiryntów, niejasnych odniesień” – zaznacza Nader. Jedno z takich nawiązań dotyczy słynnych cyklów Francisco Goyi Kaprysy, Okrucieństwa wojny i Szaleństwa. Pierwsza z serii grafik to 80 prac z lat 1798-1799, w których hiszpański artysta przedstawia zdeformowane wizerunki arystokracji i duchowieństwa. W drugiej ukazał okupację Hiszpanii przez wojska napoleońskie (1808-1814), powstania niepodległościowe i ich tłumienie przez Francuzów. Trzecia to zespół 22 rycin z lat 1815-1823, mrocznych rysunków przypominających senne koszmary.

Goya kilkukrotnie przedstawiał unoszące się w powietrzu postaci, jednak układ spadających postaci w Tańczący I zdaje się szczególnie bliski grafice nr 30 z Los Desastres de la Guerra. Dla postaci w Tańczących III, odzianej w tunikę przypominającą sanbenito, znajdziemy figury pokrewne w Capricios nr 80, a także w rysunku Fantasma baile con castañuelas z Muzeum Prado, przedstawiającym tańczącą zjawę z kastanietami. Sam strój sanbenito także widnieje na dziełach Goi poświęconych auto-da-fé.

![goya_estragos_de_la_guerra_comp.jpg [484.80 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/235d0e4bb3e58ef503b8e9dda8f6a49f/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_estragos_de_la_guerra_comp.jpg) Francisco Goya, Estragos de la guerra (Spustoszenia wojny), rycina 30 z cyklu Okrucieństwa wojny Prado

Francisco Goya, Estragos de la guerra (Spustoszenia wojny), rycina 30 z cyklu Okrucieństwa wojny Prado

– pisze Rypson. Z kolei szkice z cyklu Zabawa ludowa przypominają tańczących z płyty nr 12 cyklu Szaleństwa (Disparate allegre), a zwłaszcza pogrążony w rozpasanym tańcu tłum na słynnym obrazie Pogrzeb sardynki. „Pozornie pogodny festyn zamykający trzydniowy karnawał w Madrycie, pełen jest niepokoju, niekontrolowanej przemocy, mrocznych sił skrywanych pod maskami tańczących” – pisze Rypson. W warunkach wojny nawiązanie do Goi zyskuje szczególny wymiar:

Bohaterami jego [Wejmana] grafik i szkiców są osoby bezbronne, biorące udział w rodzaju teatru społecznego, których status jest podkreślony wyróżniającym je strojem lub nagością. Są to osoby wystawione na ogląd gapiów. Na metaforycznej scenie występują więc „inni”, bezbronni, a obok nich ci, którzy na różne sposoby „wprawiają ich w ruch”, a także patrzący na nich, bardziej lub mniej obojętni. Dlatego moja lektura Tańczących jest jednoznaczna: Mieczysław Wejman rejestruje sytuację Żydów w Warszawie podczas okupacji niemieckiej.

![goya_fantasma_con_castañuelas_comp.jpg [485.01 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/34260eaa1210ef69bf5c26258a2a0236/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_fantasma_con_casta%C3%B1uelas_comp.jpg) Francisco Goya – Fantasma con castañuelas (Duch z kastanietami),Prado

Francisco Goya – Fantasma con castañuelas (Duch z kastanietami),Prado

Zacieranie i różnicaCo uderzające, cykl Wejmana przez dziesięciolecia pozostawał w cieniu, nie był interpretowany jako świadectwo Zagłady. „Ezopowy język opisu towarzyszył tym pracom w zasadzie od samego początku” – zauważa Rypson. Wpływ na to miała cenzura PRL, która zazwyczaj nie pozwalała na uwypuklanie zagłady Żydów jako szczególnego zdarzenia, a szczególnie ograniczała możliwość mówienia o przewinach Polaków wobec Żydów.

W interpretacjach pojawiają się takie określenia cyklu Wejmana, jak „nastrój nadrealności najwyższej klasy” (Jerzy Madeyski, 1969), „rozwinięta fantastyka, jakby przemieszanie tradycji Kaprysów, Przysłów i Szaleństw Goi z nowoczesnym surrealizmem i symbolizmem” (Tomasz Gryglewicz, 2006) czy „apokaliptyczna wizja moralnego niepokoju i upadku człowieka” (Małgorzata Krzyżanowska, 2014). O ile Madeyski po nagonce antysemickiej 1968 roku nie mógłby powiedzieć wprost o losach Żydów podczas okupacji, o tyle brak wzmianki o nich u Gryglewicza czy Krzyżanowskiej powinien zastanawiać. Losów Żydów warszawskich nie należy pomijać, jeśli weźmiemy pod uwagę, jak wyjątkowość Zagłady była zacierana w oficjalnej historiografii PRL i jak jeszcze dziś pozostaje często na marginesie świadomości Polaków.

![goya_entierro_de_la_sardina_comp.jpg [497.71 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/5/26/300494a0bad1c3ed45b2015727bdd5e6/jpg/jhi/preview/goya_entierro_de_la_sardina_comp.jpg) Fransisco Goya, Pogrzeb sardynki, 1812-1819 (?) Królewska Akademia Sztuk Pięknych św. Ferdynanda w Madrycie

Fransisco Goya, Pogrzeb sardynki, 1812-1819 (?) Królewska Akademia Sztuk Pięknych św. Ferdynanda w Madrycie

Wejman „w swoim cyklu akcentuje właśnie różnicę pomiędzy jednymi a drugimi, między Polakami a Żydami, mieszkańcami getta i obserwatorami” – pisze Rypson. – „Czyni tak na różne sposoby: teatralizując przedstawiane sceny, separując niektóre postaci za pomocą kostiumu lub braku odzienia, poprzez postawy, pokazując wyobcowanie z grupy”.

Monstrualność Zagłady, ale i jej powszedniość powracały w pamięci artysty, której zapisy po raz pierwszy w tak szerokim wyborze pokazujemy na naszej wystawie. Ekspresja, odpychająca gra kolorów prac takich jak Ekshumacja czy W schronie nie tylko oddają nastrój i grozę tego czasu, lecz także odsłaniają wrażliwość obserwatora, który zatrzymał dla nas te poruszające obrazy bolesnej pamięci.

Źródła:

Luiza Nader, Teatr i mur. Tańczący Mieczysława Wejmana, w: Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman, red. Piotr Rypson, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warszawa 2022.

Piotr Rypson, Kto tańczy pod murem? Wojenne grafiki i szkice Mieczysława Wejmana, w: Tańczący 1944. Mieczysław Wejman, dz. cyt.

![norweskie_belka_PL_od_11.2021.jpg [117.19 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/11/17/e272578ab4c7b67cefab77cc42a555a1/jpg/jhi/preview/norweskie_belka_PL_od_11.2021.jpg)

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com