Gramofon model JUNIOR, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

Gramofon model JUNIOR, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

DUMA, ZABAWA I MILCZENIE – ROZMOWA Z TAMARĄ SZTYMĄ

DUMA, ZABAWA I MILCZENIE – ROZMOWA Z TAMARĄ SZTYMĄ

IDA ŚWIERKOCKA

IDA ŚWIERKOCKA: „Jak Żydek umie tylko grać, to w świecie on nie zginie” – śpiewała przed laty Ordonówna do tekstu Tuwima. W polskiej kulturze wciąż silnie obecna jest figura Żyda – muzyka, grajka, który niekoniecznie zna nuty, ale ma za to iskrę bożą i talent. Czy to jak w przypadku Żyda – handlarza kolejny stereotyp?

TAMARA SZTYMA: Muzyka zawsze odgrywała bardzo ważną rolę w tradycji żydowskiej. W klasycznym dualizmie obraz–dźwięk słuch dla Żydów był zawsze ważniejszy niż wzrok. Muzyka i śpiew towarzyszyły wszystkim ważnym żydowskim obrzędom. Od XVIII wieku orkiestry klezmerskie przemierzały miasta, miasteczka i wsie Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej i grały podczas ceremonii weselnych i innych ważnych uroczystości, a także w karczmach i na dworach szlacheckich. Z czasem zaczęły funkcjonować duże klany klezmerskie – syn dziedziczył profesję po ojcu i był do tego zawodu przez niego starannie przygotowany. Figura grajka Żyda wciąż jest bardzo silna, stąd chociażby słynny Mickiewiczowski Jankiel.

Dla nas, Polaków, koncert Jankiela miał wyraźny kontekst patriotyczny. U Żydów chyba na plan pierwszy wysuwały się kwestie związane z duchowością?

Muzyka zawsze była dla Żydów emanacją spraw duchowych. Poprzez nią najchętniej wyrażali swoje uczucia religijne. Gdy słucha się śpiewu kantora przewodzącego modlitwom w synagodze, od razu słychać tę pasję. Również muzyka klezmerska jest pełna niezwykle silnych emocji.

Szafa grająca! Żydowskie stulecie na szelaku i winylu

Na wystawie w Muzeum POLIN posłuchać można muzyki kantoralnej, utworów teatru jidysz, popularnych piosenek z filmów, rewii i musicali, muzyki jazzowej, folkowej, popowej, punkowej, a także współczesnej awangardy muzycznej reinterpretującej żydowską tradycję.

W POLIN prezentowane są też oryginalne fonografy i gramofony pozyskane od polskich kolekcjonerów. Jedną z największych atrakcji jest autentyczna szafa grająca, w której każdy ze zwiedzających może odtworzyć interesujący go utwór. Osobna, górna część ekspozycji poświęcona jest nowej muzyce żydowskiej tworzonej w Polsce na przestrzeni kilkunastu ostatnich lat.

Wystawa jest czynna do 29 maja

Jak to jest, że każde dziecko słyszało o Franklinie i Gutenbergu, i o Edisonie – ale jako o wynalazcy żarówki, a nie fonografu – o istnieniu Emila Berlinera wiedzą tylko nieliczni?

W naszej koncepcji edukacji zupełnie inaczej patrzy się na wynalazki praktyczne, które służą większej efektywności pracy. A muzykę – podobnie jak sztukę i całą kulturę – traktuje się raczej marginalnie, jako coś błahego, przyjemność, nieznaczącą zbyt wiele rozrywkę. Nikt w szkole nie czuje się więc w obowiązku, aby uczyć dzieci, kto wynalazł gramofon. Nawet gdy przygotowywałam się do tej wystawy, wiele osób mówiło mi, że to będzie taka lekka, przyjemna ekspozycja, ale która poza rozrywką nie wniesie nic większego. Okazuje się jednak, że „Szafa…” wzbudza duże zainteresowanie i że poprzez – pozornie błahą – opowieść o muzyce można powiedzieć o wiele więcej na temat żydowskiej kultury i jej związków z kulturą światową i polską.

Jeśli już ktoś usłyszy gdzieś imię i nazwisko „Emil Berliner” i zechce sprawdzić w encyklopedii, kim był, to przeczyta, że to – zacytuję prosto z Encyklopedii PWN – „amerykański elektrotechnik i wynalazca, pochodzenia niemieckiego”. Dlaczego to żydowskie pochodzenie jest marginalizowane?

W Polsce wciąż mówienie o tym, że ktoś jest Żydem, jest piętnujące. Tak naprawdę jesteśmy cały czas obciążeni postholokaustową traumą. Żyjemy w kraju, w którym przez wiele lat była tworzona wizja sztucznej homogenicznej polskości. Żydzi musieli chować głęboko do szafy swoją tożsamość. Na Zachodzie mówienie o tym, że ktoś ma jakieś korzenie, że wywodzi się z danej tradycji, jest rzeczą zupełnie naturalną. Tam głęboko w świadomości funkcjonuje coś takiego jak wielokulturowość, coś, co pomaga zrozumieć to, że mamy różne, często złożone, tożsamości. My – Polacy – od dłuższego czasu nie byliśmy uczeni tej perspektywy wielokulturowej, ale perspektywy homogenicznej.

Do tej pory mówiliśmy o mężczyznach. Jak wyglądała emancypacja muzyczna u żydowskich kobiet?

Gramofon na monety, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

Gramofon na monety, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

W tradycyjnej żydowskiej kulturze role przypisane kobietom i mężczyznom były zupełnie inne. Ta dychotomia była bardzo silna. W ortodoksyjnych synagogach kobiety nie mogły uczestniczyć w modlitwach razem z mężczyznami, siedziały w osobno wydzielonym pomieszczeniu, czyli babińcu. Nie mogły nawet marzyć o tym, by być kantorkami. Kobieta była ograniczona do sfery domowej, chociaż odgrywała bardzo ważną rolę, ale jednak zawsze prywatnie, a nie publicznie.

W reformowanym judaizmie w XX wieku zdarzały się jednak przypadki kobiet kantorek. Na wystawie można zobaczyć płytę Jean Gornish znanej jako Sheindele, córki kantora z Filadelfii, która sama już w końcu lat 30. została kantorką, występując też w radio i nagrywając na płytach.

Kobiety pochodzenia żydowskiego musiały więc – jak zwykle – przebyć zdecydowanie trudniejszą drogę, by zajmować się muzyką?

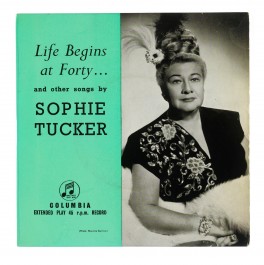

Kobiece bohaterki wystawy w POLIN to bardzo silne osobowości. Musiały mieć w sobie mnóstwo odwagi i siły, aby pokonać tak wiele barier i stereotypów. Taką postacią jest Sophie Tucker, która jest moim największym prywatnym odkryciem tej wystawy. Jej droga z dalekiej Ukrainy do Stanów Zjednoczonych była bardzo wyboista. To historia jak z filmu. Sophie miała niezwykle trudne początki, ale robiła wszystko, by śpiewać i zostać gwiazdą. Karierę zaczynała jako black face, śpiewając z pomalowaną na czarno twarzą jazzującą muzykę z południa Ameryki. Czarnoskórzy Amerykanie nie mogli wówczas występować przed białą publicznością. W ten sposób zaczynało wielu piosenkarzy pochodzących z żydowskich rodzin, dzieci emigrantów. Ale w tekstach Sophie jest sporo o sile kobiet, o ich niezależności, o bezkompromisowości. Jest taka piękna piosenka „Life Begins at Forty” o wyzbywaniu się kompleksów, o sile dojrzałości.

Sophie Tucker jest dziś jedną z ikon amerykańskich feministek. Ale wydaje mi się, że takie kwestie pojawiają się nawet u hollywoodzkich gwiazd?

Gramofon firmy Odeon, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

Gramofon firmy Odeon, fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

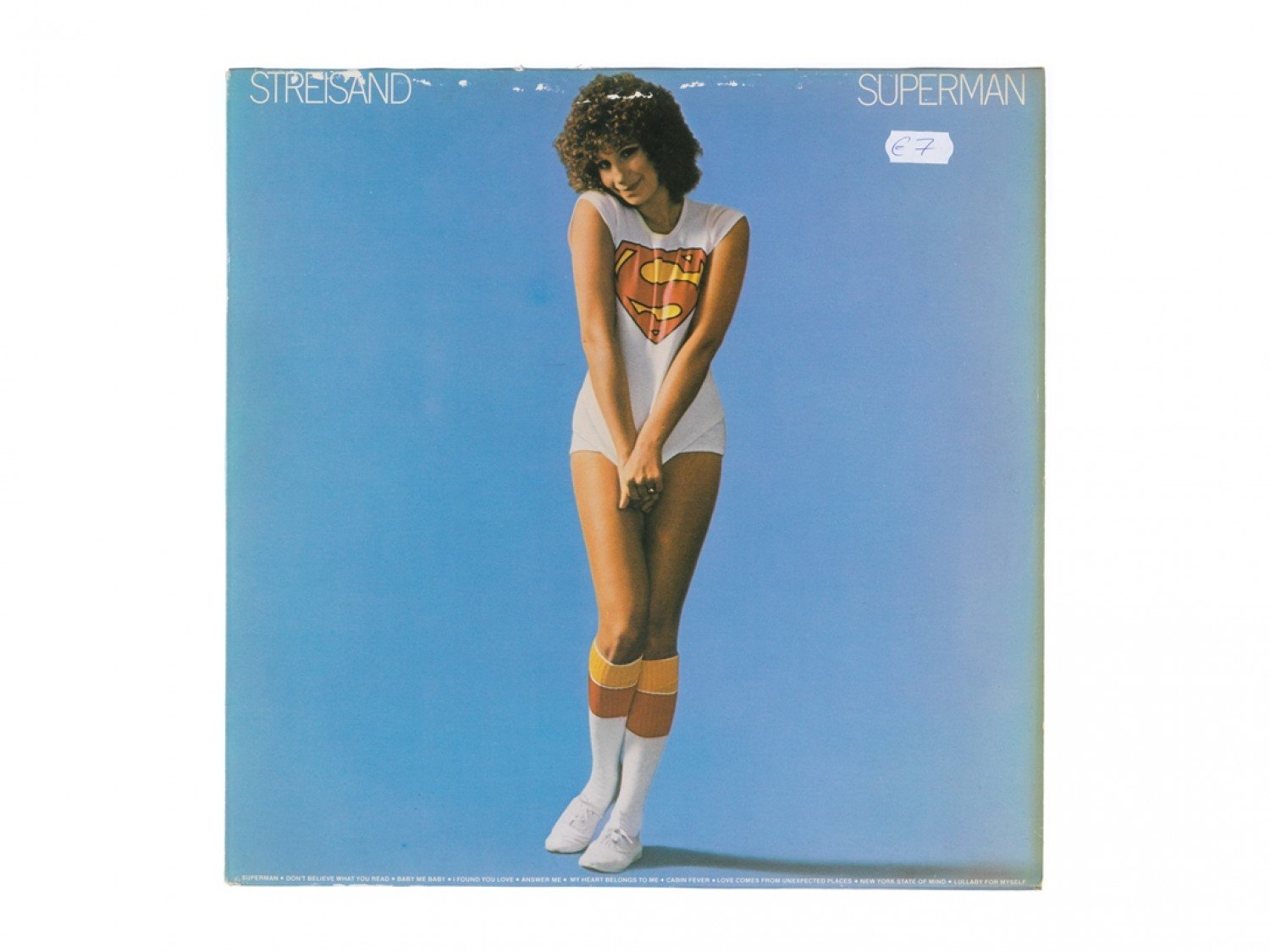

Oczywiście, tego typu wątki znajdziemy chociażby w twórczości Barbry Streisand. Choć jest ona typową gwiazdą pop, w swoich tekstach nie zapomina o drodze, którą kobiety musiały przebyć. Mimo że sama miała już zdecydowanie łatwiejszy start niż Sophie. W filmie „Yentl” Streisand sprytnie rozprawia się z wykluczeniem kobiet w tradycyjnych żydowskich społecznościach. To właśnie ona do amerykańskiej popkultury wnosi taką figurę żydowskiej emancypantki. Wystarczy posłuchać utworów „By Myself” czy „On my Own”.

Wspomniała pani o tym, że wciąż podchodzi się inaczej do wielokulturowości w Polsce i na Zachodzie. Wystawa „Szafa…” pokazywana była już w innych krajach, a jej główny kurator i pomysłodawca Hanno Loewy jest Austriakiem. Jak pracowało się z kimś, kto, choć doskonale zna żydowską kulturę, nie jest obarczony doświadczeniem postholokaustowej traumy w naszym rozumieniu tych słów?

Hanno Loewy jest świetnym kuratorem, dyrektorem Jewish Museum Hohenems i przewodniczącym European Association of Jewish Museums. Nasza praca musiała jednak łączyć się z wieloma godzinami rozmów. Dla niego robienie tego typu wystawy w Austrii czy w Wielkiej Brytanii nie jest niczym nadzwyczajnym. Tam wielokulturowość odbierana jest jako naturalny czynnik kształtujący życie społeczne. Nikt nie wstydzi się swoich korzeni czy tradycji. U nas jest to nadal nowa perspektywa, której wciąż się uczymy, którą próbujemy zrozumieć.

Tłumaczyłam Hanno Loewy’emu, że będziemy musieli włożyć dużo pracy w samo już komunikowanie wystawy. Zaznaczałam, że tutaj niezbędny jest bardzo mocny komentarz. Nie chciałam, żeby odwiedzający myśleli, że zaprezentowanie skrawka historii muzyki popularnej jest pretekstem do pokazania, że ktoś jest Żydem i przez to jest jakiś – lepszy czy gorszy. Moim celem było przedstawienie tej wielokulturowości na zupełnym luzie, bez żadnych kompleksów, bez oceny.

Tłumaczyłam Hanno Loewy’emu, że będziemy musieli włożyć dużo pracy w samo już komunikowanie wystawy. Zaznaczałam, że tutaj niezbędny jest bardzo mocny komentarz. Nie chciałam, żeby odwiedzający myśleli, że zaprezentowanie skrawka historii muzyki popularnej jest pretekstem do pokazania, że ktoś jest Żydem i przez to jest jakiś – lepszy czy gorszy. Moim celem było przedstawienie tej wielokulturowości na zupełnym luzie, bez żadnych kompleksów, bez oceny.

Zebrali państwo w jednym miejscu wielką liczbę twórców żydowskiego pochodzenia. Ale wystarczy przeczytać nazwiska tych osób – większość z nich nie brzmi „po żydowsku”.

Dlaczego zasymilowani polscy Żydzi woleli nazywać się po polsku (np. Włast) lub „po amerykańsku” (np. Aston)?

Dlaczego zasymilowani polscy Żydzi woleli nazywać się po polsku (np. Włast) lub „po amerykańsku” (np. Aston)?

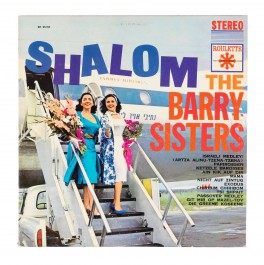

Działa tu klasyczny mechanizm znany z antropologii. Mniejszość zawsze musi dopasować się do większości. Osoba z mniejszości aspirująca do dołączenia do większości, nawet jeśli jest najzdolniejsza na świecie, często ma poczucie, że po prostu musi więcej. Dlatego też niejednokrotnie Żydzi osiągali tak wiele. To „bycie na niższej pozycji” działało na nich stymulująco. Musimy pamiętać jednak o tym, że polska kultura międzywojenna była zapatrzona w Zachód. Długie żydowskie nazwiska nie były po prostu tak sexy jak amerykańskie. W Stanach Zjednoczonych Żydzi też zmieniali nazwiska, ale tutaj chodziło głównie o brzmienie i łatwiejszą wymowę. Słynne The Barry Sisters były przecież siostrami Bagelman.

Ten mechanizm dopasowywania się działał tak mocno, że większość żydowskich twórców doskonale znała nawet najgłębsze zakamarki polskiej kultury. Dla mnie jednym z większych odkryć tej wystawy jest to, że miejski folklor Warszawy jest w dużej mierze żydowski.

W Warszawie międzywojennej większość Żydów należała do nizin społecznych. Wielu było robotnikami. Ta polska część kultury popularnej niezwykle intensywnie zazębiała się z żydowską. Utwory takie jak „Nie masz cwaniaka nad warszawiaka” czy „U cioci na imieninach”, które śpiewali Grzesiuk, Wielanek i inni warszawscy artyści, stworzyli – o czym nie wszyscy wiedzą – tekściarze i kompozytorzy pochodzenia żydowskiego. Nie zapominali jednak oni o swoich korzeniach i chętnie przemycali do tego warszawskiego świata i półświatka motywy żydowskie, czego świadectwem jest chociażby słynny „Bal na Gnojnej”. Podobnie wyglądało to we Lwowie, gdzie tworzyli Marian Hemar, Henryk Wars i Emanuel Szlechter.

W Warszawie międzywojennej większość Żydów należała do nizin społecznych. Wielu było robotnikami. Ta polska część kultury popularnej niezwykle intensywnie zazębiała się z żydowską. Utwory takie jak „Nie masz cwaniaka nad warszawiaka” czy „U cioci na imieninach”, które śpiewali Grzesiuk, Wielanek i inni warszawscy artyści, stworzyli – o czym nie wszyscy wiedzą – tekściarze i kompozytorzy pochodzenia żydowskiego. Nie zapominali jednak oni o swoich korzeniach i chętnie przemycali do tego warszawskiego świata i półświatka motywy żydowskie, czego świadectwem jest chociażby słynny „Bal na Gnojnej”. Podobnie wyglądało to we Lwowie, gdzie tworzyli Marian Hemar, Henryk Wars i Emanuel Szlechter.

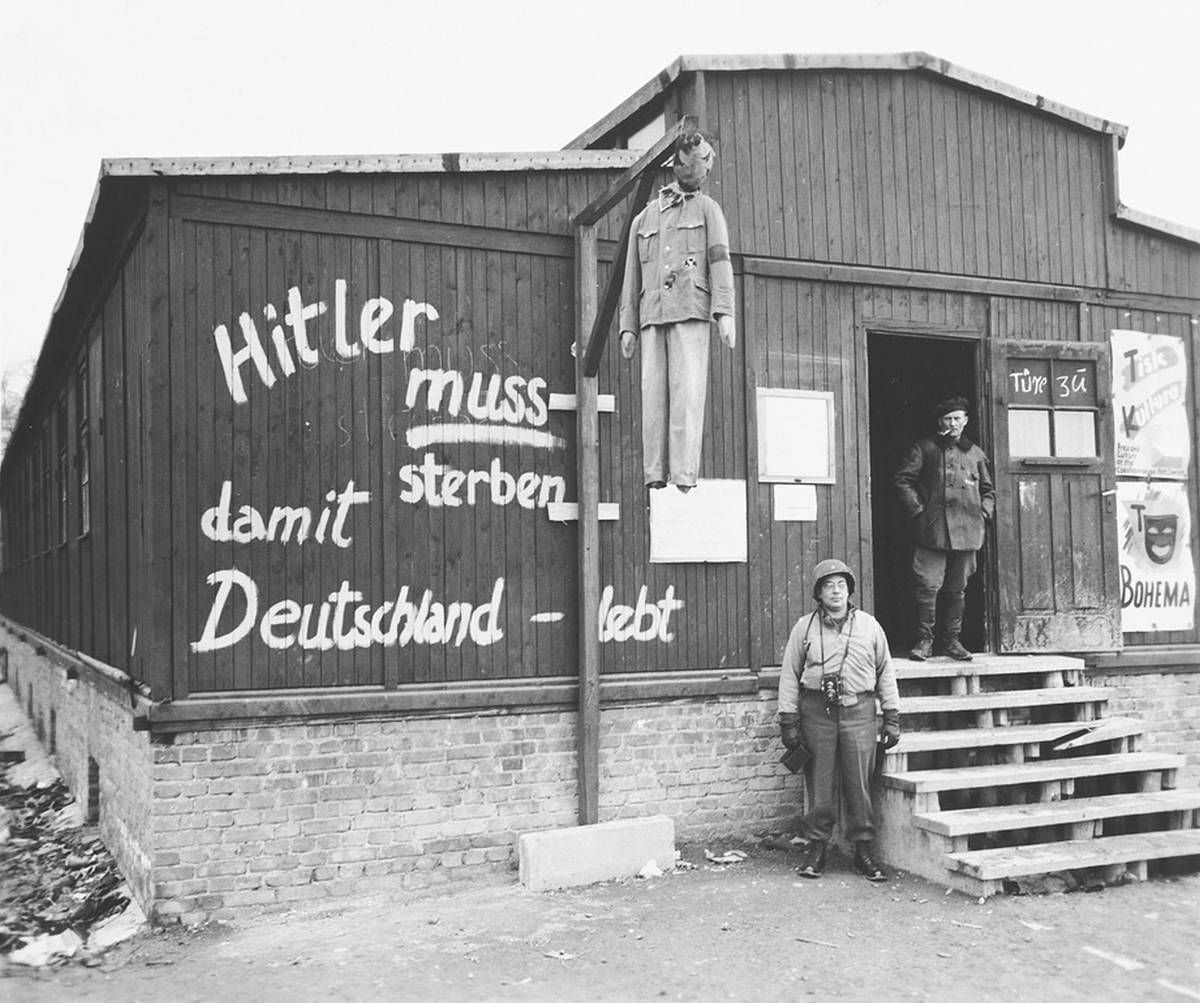

A jak było podczas wojny? O muzyce w gettach wiadomo bardzo niewiele, tyle co z „Pianisty” Polańskiego czy książki o Wierze Gran Tuszyńskiej. Jak Żydzi próbowali zachować pozory normalności w tych czasach?

W gettach, zwłaszcza tych większych, funkcjonowały kawiarnie, kluby muzyczne, kabarety i teatrzyki. Historie Wiery Gran, Marysi Eisenstadt, Władysława Szpilmana dobitnie pokazują, że z jednej strony muzyka była zwykłą walką o przeżycie, z drugiej zaś – walką o siebie samego, o swoją pasję, o zachowanie nawet pozornej normalności.

Tamara Sztyma

Ur. 1975, historyczka sztuki i kuratorka wystaw; absolwentka historii sztuki UW, podyplomowych studiów żydowskich w Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies oraz studiów doktoranckich z zakresu nauk o sztuce na UMK. Od 2013 roku pracuje jako kuratorka wystaw w Muzeum POLIN. W latach 2008–2013 pracowała w zespole przygotowującym wystawę stałą tego muzeum, gdzie zajmowała się galerią międzywojenną.

Mam jednak wrażenie, że o ile o muzyce przedwojennej mówi się dużo i chętnie, o tyle muzyka podczas wojny, a zwłaszcza już – muzyka w getcie – wciąż pozostaje tematem marginalnym. Tak jakby kultura traktowana była jako nic nieznacząca fanaberia.

Jeśli rzeczywiście ten mechanizm wciąż działa, to dlatego, że samo mówienie o muzyce w getcie wymaga komentarza, podania szerszego kontekstu. Gdyby nawet zachował się występ z rewii „Szafa gra”, w której śpiewała Wiera Gran, to nie wyobrażam sobie, aby został on zaprezentowany tutaj bez odpowiedniego ulokowania go w sytuacji historycznej. Piosenka nie służyła wtedy wyłącznie rozrywce, choć tego komponentu nie można też jej odbierać.

Jak muzyka żydowska funkcjonowała w PRL-u – kraju, w którym wiele zjawisk kultury popularnej było dyskryminowanych?

Przed wojną na Zachodzie i w Polsce kultura żydowska rozwijały się bardzo podobnie. Żydzi mieli bardzo duży udział w rozwoju branży fonograficznej, filmu i kabaretu. Po wojnie zamiast kolorowej, barwnej popkultury mieliśmy cenzurę i jedną wytwórnię płytową.

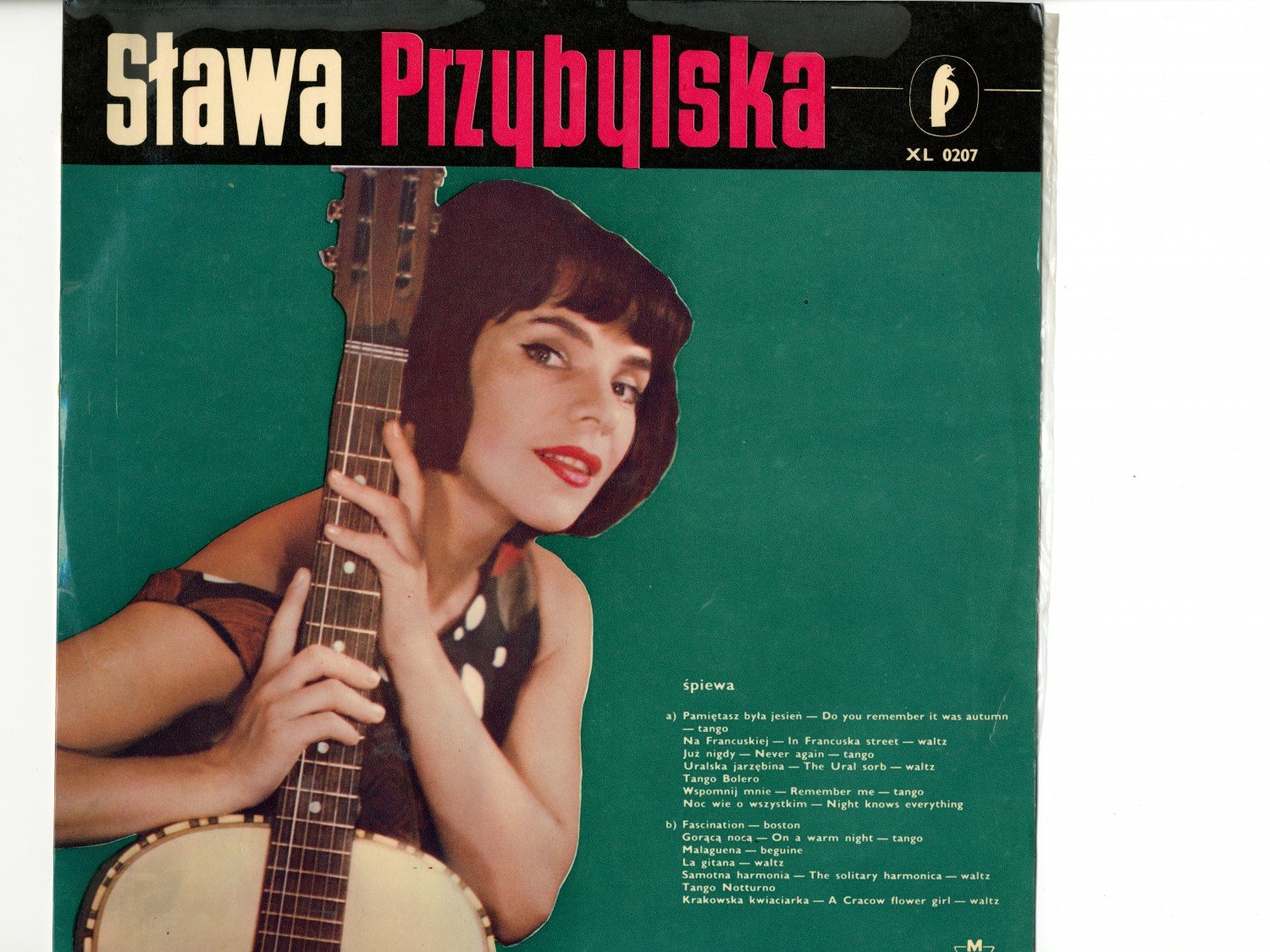

Wielu piosenkarzy śpiewało jednak dawne przeboje, np. Ewa Demarczyk, Sława Przybylska czy Staszek Wielanek.  Holocaust i późniejsza emigracja mocno ograniczyły żydowskie wpływy. Żydzi, którzy zdecydowali się zostać, chowali swoją tożsamość głęboko, nie chcieli w ogóle o niej mówić. Na Zachodzie gwiazdy muzyki pop dumnie podkreślały swoje żydowskie korzenie albo odwrotnie – z równie wielkim zapałem kontestowały je lub po prostu się nimi bawiły. U nas tego tematu w ogóle nie było, bo żydowskość była cały czas silnie straumatyzowana. Dlatego dzieje Żydów w Polsce po wojnie nazywane bywają „historią milczenia” lub „historią braku”.

Holocaust i późniejsza emigracja mocno ograniczyły żydowskie wpływy. Żydzi, którzy zdecydowali się zostać, chowali swoją tożsamość głęboko, nie chcieli w ogóle o niej mówić. Na Zachodzie gwiazdy muzyki pop dumnie podkreślały swoje żydowskie korzenie albo odwrotnie – z równie wielkim zapałem kontestowały je lub po prostu się nimi bawiły. U nas tego tematu w ogóle nie było, bo żydowskość była cały czas silnie straumatyzowana. Dlatego dzieje Żydów w Polsce po wojnie nazywane bywają „historią milczenia” lub „historią braku”.

Czyli obserwowane od kilku lat ogromne zainteresowanie muzyką żydowską w jej różnych aspektach jest jakby odreagowaniem tego wieloletniego milczenia?

Oczywiście, a poza tym tradycyjna muzyka żydowska zawsze była silnie związana ze sferą duchową, co jest bardzo atrakcyjne dla współczesnych muzyków, którzy chętnie łączą historyczne elementy tej muzyki z nowymi, niekiedy zupełnie zaskakującymi, brzmieniami. Bez wątpienia artystów przyciąga też naznaczony silnymi emocjami tragizm, który jest nieodłącznie związany z pełną wzlotów i upadków historią Żydów.

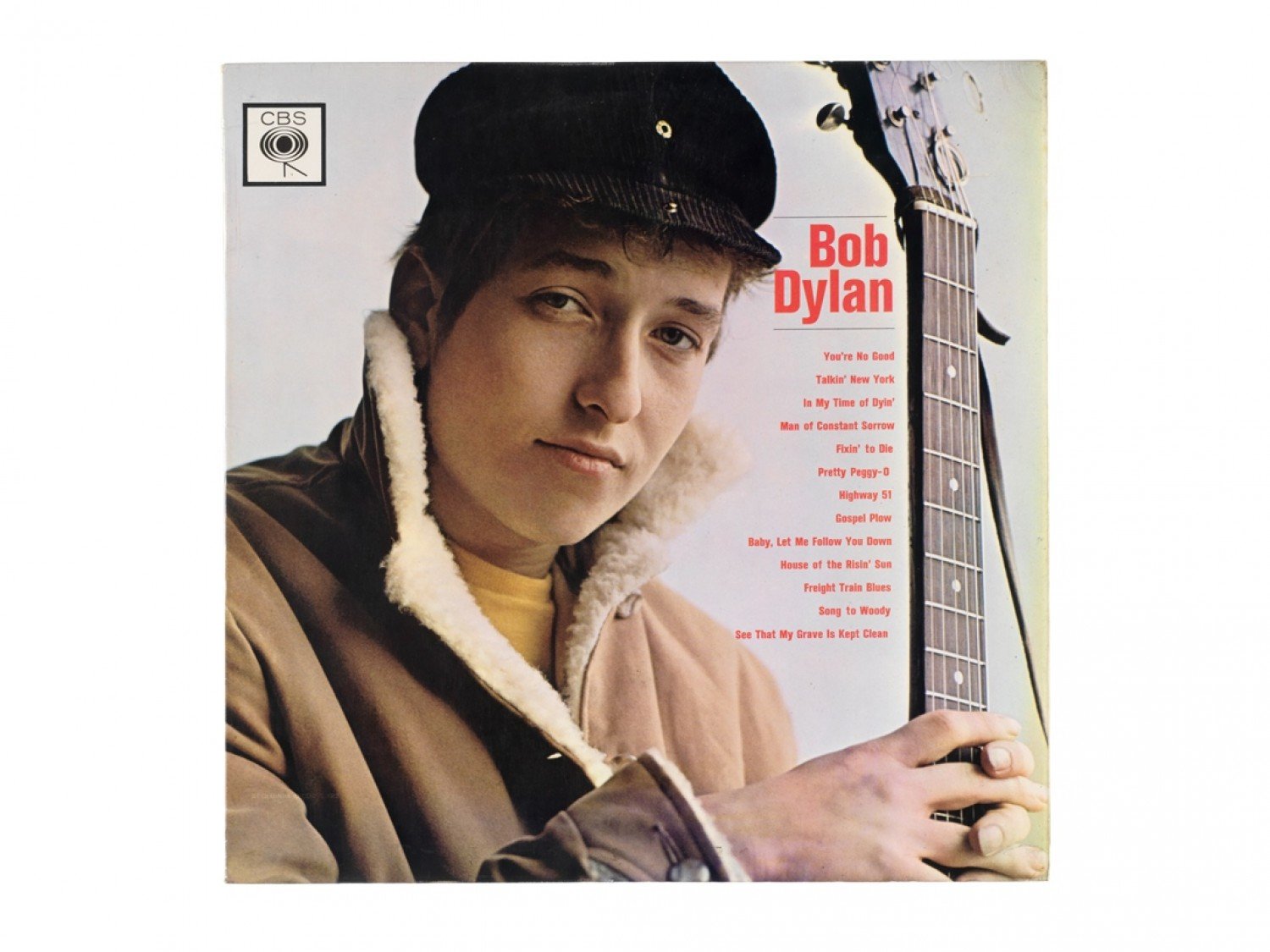

Użyła pani określenia „zabawa korzeniami żydowskimi” w stosunku do zachodnich artystów. Taką najbardziej oczywistą ikoną jest tu Bob Dylan, który przeszedł ogromną drogę w swoich duchowych poszukiwaniach.

Tak, Bob Dylan pochodzi z rodziny żydowskiej, która na początku

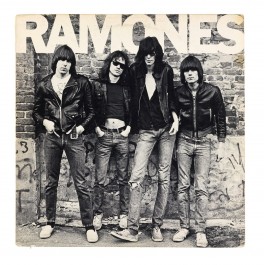

poprzedniego wieku przybyła z Rosji do Ameryki Północnej. Jego poszukiwania tożsamości były niezwykle interesujące – przeszedł na chrześcijaństwo, grał przecież dla papieża, ale w końcu odnalazł się, zgodnie z rodzinną tradycją, w judaizmie, co znalazło odzwierciedlenie w jego tekstach. Artystyczny wizerunek, jaki stworzył, niepokój duchowy, który wyobrażał w swojej twórczości, aż proszą o przywołanie archetypicznej figury Ahaswera, Żyda Wiecznego Tułacza. Innym takim bohaterem był oczywiście Leonard Cohen, który łączył klasyczny kościelny gospel z przejmującymi tekstami dotyczącymi na przykład wyjścia Żydów z niewoli. Nie można zapominać też o żydowskich korzeniach punkowców i postpunkowców z Nowego Jorku. The Ramones, Lou Reed, The Dictators jawnie, choć przecież w nieoczywisty sposób żonglowali motywami ze swojej sfery kulturowej. Podobnie jak londyński The Clash. Inną ikoną jest Amy Winehouse, która już jako dziewczynka założyła zespół, który później żartobliwie nazywała „żydowskim odzwierciedleniem zespołu Salt-N-Pepa”.

poprzedniego wieku przybyła z Rosji do Ameryki Północnej. Jego poszukiwania tożsamości były niezwykle interesujące – przeszedł na chrześcijaństwo, grał przecież dla papieża, ale w końcu odnalazł się, zgodnie z rodzinną tradycją, w judaizmie, co znalazło odzwierciedlenie w jego tekstach. Artystyczny wizerunek, jaki stworzył, niepokój duchowy, który wyobrażał w swojej twórczości, aż proszą o przywołanie archetypicznej figury Ahaswera, Żyda Wiecznego Tułacza. Innym takim bohaterem był oczywiście Leonard Cohen, który łączył klasyczny kościelny gospel z przejmującymi tekstami dotyczącymi na przykład wyjścia Żydów z niewoli. Nie można zapominać też o żydowskich korzeniach punkowców i postpunkowców z Nowego Jorku. The Ramones, Lou Reed, The Dictators jawnie, choć przecież w nieoczywisty sposób żonglowali motywami ze swojej sfery kulturowej. Podobnie jak londyński The Clash. Inną ikoną jest Amy Winehouse, która już jako dziewczynka założyła zespół, który później żartobliwie nazywała „żydowskim odzwierciedleniem zespołu Salt-N-Pepa”.

fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

fot. M. Starowieyska / Muzeum POLIN

Na górnej części wystawy można posłuchać najnowszej żydowskiej muzyki tworzonej w Polsce (a nawet spróbować swoich sił w grze na perkusji). Najciekawsi polscy muzycy młodego i średniego pokolenia nawiązują do żydowskich tradycji muzycznych. Przeżywamy odrodzenie tej muzyki w Polsce?

Rzeczywiście od kilkunastu lat obserwuje się u nas ogromne zainteresowanie brzmieniami muzyki żydowskiej. Dużą rolę odegrały i odgrywają tu festiwale, takie jak Festiwal Kultury Żydowskiej w Krakowie, Tzadik Poznań Festival, Festiwal Nowa Muzyka Żydowska, Festiwal Warszawa Singera oraz kluby muzyczne, jak choćby zamykany właśnie Pardon, To Tu. Nie bez znaczenia jest też działalność sceny muzycznej Muzeum POLIN. Rahpael Rogiński, Mikołaj Trzaska, Paweł Szamburski, Ola Bilińska, Wacław Zimpel, Jarosław Bester, Karolina Cicha – twórców eksperymentujących z tradycyjnymi żydowskimi brzmieniami jest dziś mnóstwo. Każdy oczywiście interpretuje muzykę w swój własny, autorski sposób. Ta wystawa pokazuje jeszcze jedną ciekawą rzecz: nowa muzyka żydowska jest dziś tworzona głównie przez nie-Żydów, także dla nie-Żydów i staje się częścią sfery uniwersalnej.

IDA ŚWIERKOCKA – Ur. 1988, dziennikarka i redaktorka. Absolwentka kulturoznawstwa i socjologii. Współpracuje m.in. z „Wysokimi Obcasami” i magazynem „Skarpa”. Pracuje nad książką o przedwojennej Warszawie.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com