You will watch your parents die and be buried. You will watch your newborn child emerge in a messy circus of heaving grunts and high-pitched wailing. You will watch your dreams and projects dashed, only to wake the next day and greet the fruits of your failure anew and cobble a life out of them all the same. You will punctuate the cavalcade of events with moments of transcendent meaning that will linger in memory like fading signposts during that final moment: your death.

Navigating that journey without a religious tradition is like trying to cross open country without a path: You can do so, but you’ll do lots of stumbling and very likely lose your way. Trying to get through dense woods—a serious depression, the death of a loved one—without a marked trail requires the most arduous labor for the merest progress. Furthermore, if you tackle these wilds in their raw and uncleared state, you will almost certainly do so alone. Going off-trail means a hard solitary journey, while the marked trail involves communal groups headed in your same direction. What some might describe as a cultural rut—some timeworn lane that limits movement—might just be the only thing that guides you through this daunting wilderness of life whose many paths all end in the same destination.

To DIY your own world of life signifiers, you have to think you can improve on a bar mitzvah as a coming-of-age ritual, on Shabbat as a form of digital detox, and on teshuvah as a way to grapple with your guilt (or analogs in other religious traditions). Many do of course, and every trendy San Franciscan has their personal regimen of special diets, meditation schedules, intermittent fasts, escapes to nature, a canon of mimetic culture usually drawn from their online feeds, a smattering of trendy texts that inform their values, and some slew of Netflix shows that serve as cultural touchpoints with others in their cohort.

This is all in keeping with the current liberal project’s moral goal, which is creating lives devoid of any unchosen obligations and absolutely rife with chosen identities of fanciful and recent coinage. The problem is that it’s the unchosen obligations—or the obligations chosen but whose downstream responsibilities cannot be unchosen—that will give us the only real meaning in life. Family, children, our hometowns, our childhoods, our ethnic identity (if we have one), or the chosen-but-undoable commitments—marriage, joining the military, that company we start, religious faith—are the defining obligations where our selves really play out.

If I were to go back and say one thing to my younger self as a warning from the future, it’s this: The eventual cost of optionality in life—all the commitments you don’t make to preserve your ability to instantly change course—is usually not worth the upside that optionality eventually produces. And even when that optionality is rich indeed (and I know a thing or two about the exploding value of literal financial options), your commitment to that remunerative course, fully cognizant of your wider obligations, will serve you better than the anxious FOMO-ing of the hyperoptimizer. Which is a long way of saying that at some point you do have to “choose a hill to die on,” because if you don’t, you won’t really ever have lived at all. Here, I will attempt to lay out why you should also do so, and why I chose the Jewish hill that I did.

Every society needs a metaphysics that allows it to have moral and political conversations with itself. Liberalism’s preferred metaphysical framework of utilitarianism—in effect, ethics by Excel spreadsheet—is at best a simplistic hack that illuminates some trade-off, much as microeconomics can inform the pricing of Starbucks’ various coffee sizes. That’s assuming society can even do the hard math of exchanging one type of human well-being (or even entire lives) against others in a rational way.

It’s more than a little pathetic watching an avowedly atheist materialist society, whose epistemology ends at empiricism, play at metaphysics. It makes them suck even at empiricism, as reality must be warped to suit whatever nonempirical argument they’re incapable of expressing any other way.

Consider the epistemic chaos in the United States as every side tries to “win” COVID, and show that their side’s interpretation—vaccine mandates, mask mandates, no mandates, ivermectin, zero COVID, my cousin’s friend’s swollen balls, whatever—aligns with empirical reality, which is the only mode of reasoning about even immaterial questions. Thus the constant citation of half-assed studies (many later corrected or retracted) attempting to marshal evidence for what are effectively moral or religious stances.

The questions we should be asking are the ones that secular modernity doesn’t even possess the moral vocabulary to discuss anymore:

Do we sacrifice the old for the sake of educating the young during a pandemic?

What is the duty of the citizen to the state, and does that include collective sacrifice like vaccination?

What is the duty of the state to the citizen in presenting policy as truthfully as possible, rather than as a purportedly noble lie?

To what common good should the state intervene in our lives?

Toward what common good should we all be striving?

The answers to those questions are not to be found in any iffy study those doing online COVID battle could cite, and even our wider political culture is bereft of any coherent philosophical platform. Figures like John Rawls and Robert Nozick once provided something like a cogent political worldview (though it took Rawls several hundred pages of Harvard-level disquisition and “veils of ignorance” analogies to restate Kant’s Categorical Imperative and Matthew 7:12).

But that’s all gone now, and there’s nobody even remotely in the position of a Rawls. For the first time in my life, no political faction in the West has anything like a generative vision of the future. Your point on the current political spectrum is defined by the year to which you’d like to somehow magically return society: 2009 → Obama-ite; 1952 → conservative; 1984 → Reagan nostalgist; and so it goes.

It may well be the case that liberalism is unsustainable without a real illiberal antagonist. If none exists, one will be invented. Each political side now perpetually assures us the other side is prepping for tyranny at any moment. The thought that our government, which bungled both a pandemic response and a war against a medieval religious sect, would be capable of iron-fisted autocracy in a modern country of 330 million seems … almost wishfully ambitious in its fear.

To the extent there’s anything like a forward-looking plotline in our national conversation, it’s the old fallbacks of every (post) Christian society in a tizzy of panicked confusion: millenarian brooding about a coming apocalypse, and revivalist fervor around some utopian project or another. Beyond the latest episode in the political telenovela—Russiagate! QAnon!—what else do we talk about other than the zealous demands of wokeness and the perils of climate change?

For the first time in my life, no political faction in the West has anything like a generative vision of the future. More and more, secular modernity looks like a shaky edifice of convoluted fantasies built over an abyss.

Leaving the elevated realm of politics for the more quotidian one of personal morality and rule of law, matters aren’t going much better.

Consider for a moment the Noahide Laws of Judaism, the basic moral principles thought to apply to all humanity. In addition to the usual proscriptions around murder, theft, and adultery, we have a very unique one: the requirement to establish courts of justice to adjudicate human behavior. Without that, in the Jewish mind, humanity would live in brutish savagery.

How does our society rate against the Noahide Laws? What are our courts of justice?

Nowadays, our judges are mostly narcissistic sociopaths gaming Twitter’s engagement algorithms to get someone fired over some perceived moral lapse (this week, it was over another confused encounter involving dog-walking). This week’s online Hester Prynne was instantly fired by a corporate management happy to consider an online mob’s verdict as binding as anything from the Supreme Court. Another such duet of mob outrage coupled with corporate cowardice led to my firing from Apple (that time via the internal vector for mob mayhem, Slack).

This moral cowardice is ironic in a corporate world suddenly bursting with people with “ethics” or “equity” in their job titles. Mostly, they’re charlatans regurgitating the improvised tropes of whatever faddish academic or corporate cult has sprung up to fill the God-sized hole at the center of liberalism.

Meanwhile, politicians advocate for more and more public sacrifice around COVID while skirting their own restrictions, and the only person sitting in jail for the Afghanistan fiasco is the one officer who dared demand accountability for it. There is no real public court of justice or moral code in our modern-day world anymore, and deep down we all know it. Our current society wouldn’t pass the last and arguably most important of Noah’s Seven Laws for minimally civilized behavior.

The core problem here is that at the heart of any real political or moral reasoning, if we’re being honest with ourselves, we’re left pointing at a document or set of principles and arguing by sheer faithful assertion alone: These principles we believe to be true, and we will make decisions of life-and-death import according to these moral foundations. If you disagree, sorry, we don’t have much to talk about as we simply live in different moral universes.

Faced with the secular alternative of bitchy Twitter food fights and “cancel culture,” I choose to believe there are sterner (and wiser) judges in this universe than the blue checks of Twitter and the “People” department at companies like Apple. More and more, secular modernity looks like a shaky edifice of convoluted fantasies built over an abyss, and I for one am tired of pretending to take it seriously. Those who reject the modern sham and wish to reason seriously about politics or morality must necessarily strike a pose—half-pointing, half-saluting—toward some set of sacred principles; on the political front, I choose to salute the United States Constitution (so long as we can keep it); on the moral front, I gesture toward the Bible of the Hebrews.

We have arrived at a unique point in history where many Americans love nothing more than themselves, and the only functioning organization that touches their lives is a corporation. That’s all good and well as a single striver sprinting along our treadmill of an economic system; the above realization takes on a more somber tone when confronted with the only form of immortality available to most of us: our children.

Daddy, why is that man living in the bus stop? Daddy, why are you gone working so much? Daddy, can I read this book or watch this show? Daddy, what’s this flag I’m holding?

Suddenly questions like the ones above go from the heated but ultimately vain stuff of Twitter threads to daunting conversations with the one thing left in the world you’d sacrifice yourself to save. Those big, brown eyes staring at you demand an answer to those questions; her absolute receptiveness to your answers yokes you with a responsibility to posterity that hedonistic modernity has distracted you from your entire life. What do you put in that mind that will outlast yours?

Nowadays, the exercise seems less one of curating a personal time capsule, and more that of a shipwrecked sailor trying to salvage what’s worth keeping from a vessel (or a society) that’s foundered on a rocky shore. Much like that sailor would, we agonize over what books, and ultimately what stories, we choose to salvage and keep on reading and repeating to one another.

Consider another example drawn from the Jewish world: Most of the planet commemorates the Holocaust on Jan. 27, the day the Red Army liberated Auschwitz. Every country considers that Holocaust Remembrance Day, except the Jewish State of Israel itself. They commemorate the Holocaust on the 27th day of the Jewish month of Nisan, the day of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, when poorly armed Jews fought to the death against the Nazi war machine rather than passively submit to annihilation. The nascent state of Israel thought it important to enshrine that as the nation’s Holocaust narrative (as Yom HaShoah), rather than a narrative that had Jews passively saved, much too late, by an outside power.

As frivolous as they sometimes might seem, the stories we tell ourselves are what we ultimately become as people and a civilization. There’s perhaps no more important choice we face as stewards of the present than what we pass on to the future as shared narrative. We all subconsciously realize that, which is why the debates over the 1619 Project or critical race theory have grown so heated and deafening. With the grim examples of slavery and the Holocaust in mind, let’s revisit the question: What then do we put in our children’s heads?

For me, the choice is very simple. My children are the descendants of Holocaust survivors, refugees from an Islamic revolution, and exiles from two communist revolutions (both Russian and Cuban flavors). The 20th century, in all its turmoil, flows through their veins in the oddest of admixtures. This extended family has seen many a government fall and world implode. Many times in our collective memory, what once seemed like the bedrock firmament of a sane society was soon demolished for a fresh hell of human devising. In a present moment that seems similarly pregnant with change, I will invite my children to open one of humanity’s oldest body of works, and once again read about …

… the cunning ruthlessness of Judith willing to do anything to save her tribe; the self-indulgent hubris of David; the righteous guile of Esther; the genocidal wrath of Jacob’s sons avenging the rape of their sister Dinah; the fierce defiance of the Maccabees hellbent on saving their tradition; the murderous envy of Cain; the reluctant, bungling leadership of Moses who somehow managed a spectacular exodus; the smoldering sensuality of the Song of Songs; the evocative verses of Psalms whose catchphrases litter every Western language; the wailing nostalgia of Lamentations; the all-in loyalty of Ruth; the unshakable faith of Job; the dancing, timbrel-playing triumph of Miriam; the castigating tirades of Jeremiah; the comically inept procrastination of Jonah; finally, the existential world-weariness of Ecclesiastes.

All of humanity is there, in all its sublime or squalid expanse: An adult life will be populated by its own personal bible of Cains and Davids and Esthers. But unlike the epic characters in such timeless works as the Odyssey or Beowulf, or even distant references like Aeschylus or Shakespeare, this gallery of characters populates a still-extant tradition whose adherents sway in collective fervor every holiday.

This very week was Simchat Torah (Hebrew for “joy of the Torah”), when Jews take the Torah scrolls out of the synagogue’s ark and joyfully parade them outdoors, dancing and singing with their scripture’s heavy burden slung awkwardly on their shoulders. It marks the end of the annual cycle wherein an advancing Torah portion is read aloud every Sabbath, one turn of the scroll at a time until the very end. It is the one Jewish festival not divinely ordained nor the product of some historical event; this the Jews put on for themselves in their obsessive love for their collective story. And when all the singing and dancing is over, they immediately rewind the scroll and start reading again, as they have for millennia: “In the beginning God created heaven and Earth …”

As that scroll is returned to the ark after the reading, the gathered crowd recites: “It is a tree of life to those who hold fast to it.” Indeed it has been a tree of life to a people who made it the foundation of their civilization, a people that stubbornly persisted in a world that often wanted nothing less than their total extermination; a world that even now begrudges the Jews the tiny state they perilously safeguard.

Stuck in a secular modernity that’s lost the plot, and that no longer knows what it is or where it’s going, I choose to hold fast to that tree of life. I also say, as the loyal convert Ruth once said to Naomi: “Wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried.”

PIÓRKO Z ŻYDOWSKIEJ KOŁDRY

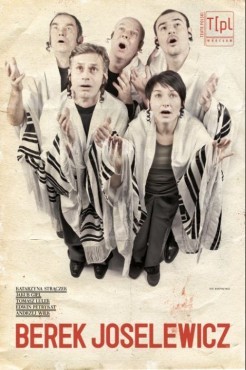

PIÓRKO Z ŻYDOWSKIEJ KOŁDRY „Berek Joselewicz” na podstawie „Roku 1794” Zenona Parviego oraz „Berka Joselewicza” Jakuba Waksmana, reż. Remigiusz Brzyk. Teatr Polski we Wrocławiu, prapremiera 19 lutego 2010Cały tekst spektaklu został przetłumaczony na jidysz. Dla kogo? Nikłe jest prawdopodobieństwo, że na widowni znajdzie się wielu takich, dla których wyświetlane na bocznych ścianach hebrajskie litery, niczym wyjęte ze wspomnień starego aktora, będą czymś więcej niż egzotycznym ornamentem. Napisy w niezrozumiałym języku są trybutem płaconym historii tego miejsca, ale też namacalnym świadectwem nieobecności. To nie wszystko: są w spektaklu sceny grane wyłącznie w jidysz, ale tym razem nikt ich na nasz język nie tłumaczy. Jakby zapomniano o nas, demonstracyjnie nas zignorowano. Chociaż chodzi raczej o naszą ignorancję i naszą niepamięć. Słuchanie aktorów mówiących w jidysz sprawia, że nagle to my czujemy się tu całkiem obcy. Dawne role zostają odwrócone. Bardzo przemyślna i dotkliwa prowokacja.

„Berek Joselewicz” na podstawie „Roku 1794” Zenona Parviego oraz „Berka Joselewicza” Jakuba Waksmana, reż. Remigiusz Brzyk. Teatr Polski we Wrocławiu, prapremiera 19 lutego 2010Cały tekst spektaklu został przetłumaczony na jidysz. Dla kogo? Nikłe jest prawdopodobieństwo, że na widowni znajdzie się wielu takich, dla których wyświetlane na bocznych ścianach hebrajskie litery, niczym wyjęte ze wspomnień starego aktora, będą czymś więcej niż egzotycznym ornamentem. Napisy w niezrozumiałym języku są trybutem płaconym historii tego miejsca, ale też namacalnym świadectwem nieobecności. To nie wszystko: są w spektaklu sceny grane wyłącznie w jidysz, ale tym razem nikt ich na nasz język nie tłumaczy. Jakby zapomniano o nas, demonstracyjnie nas zignorowano. Chociaż chodzi raczej o naszą ignorancję i naszą niepamięć. Słuchanie aktorów mówiących w jidysz sprawia, że nagle to my czujemy się tu całkiem obcy. Dawne role zostają odwrócone. Bardzo przemyślna i dotkliwa prowokacja. fot. Bartosz MazNajpewniejszym sposobem, żeby mieć w nim udział, jest śmierć za ojczyznę. Sceny walki to niekończące się umieranie. Heroiczne – bo z bronią w ręku, z „Boże coś Polskę” na ustach i pod polską flagą. Syn Berka, Józef Joselewicz (Michał Majnicz), zataczając kolejne kręgi wokół ginących powstańców, nie wypuszcza tej flagi z rąk, a żydowscy powstańcy umierają po wielokroć: zsuwają się po pochyłej scenie, wstają, walczą i znowu padają. Ta uporczywa powtarzalność choreografii śmierci jest jak pytanie: ile razy i jak spektakularnie trzeba ginąć za swój kraj, by uzyskać jego pełnoprawne obywatelstwo? Nawet Berek Joselewicz (Wiesław Cichy) musi wciąż na nowo udowadniać, że zasłużył na miano polskiego bohatera. Przedstawiając swoje zasługi dla Polski, nasuwa na oczy kaptur – na krótką chwilę staje się współczesnym chłopakiem z miasta, dla którego order Virtuti Militari jest prawdziwym powodem do dumy.

fot. Bartosz MazNajpewniejszym sposobem, żeby mieć w nim udział, jest śmierć za ojczyznę. Sceny walki to niekończące się umieranie. Heroiczne – bo z bronią w ręku, z „Boże coś Polskę” na ustach i pod polską flagą. Syn Berka, Józef Joselewicz (Michał Majnicz), zataczając kolejne kręgi wokół ginących powstańców, nie wypuszcza tej flagi z rąk, a żydowscy powstańcy umierają po wielokroć: zsuwają się po pochyłej scenie, wstają, walczą i znowu padają. Ta uporczywa powtarzalność choreografii śmierci jest jak pytanie: ile razy i jak spektakularnie trzeba ginąć za swój kraj, by uzyskać jego pełnoprawne obywatelstwo? Nawet Berek Joselewicz (Wiesław Cichy) musi wciąż na nowo udowadniać, że zasłużył na miano polskiego bohatera. Przedstawiając swoje zasługi dla Polski, nasuwa na oczy kaptur – na krótką chwilę staje się współczesnym chłopakiem z miasta, dla którego order Virtuti Militari jest prawdziwym powodem do dumy. fot. Bartosz MazPunktem wyjścia jest rok 1794, ale postacie znają fakty historyczne, jak również ich współczesne interpretacje. Zdają się też mieć pełną świadomość, co się stało przed, w czasie i po wojnie. Narracja toczy się w kilku czasach jednocześnie. Rosjanin Pałkin (Wojciech Ziemiański), przemierzając scenę z reprodukcją „Rejtana” pod pachą, wspomina, że obraz Matejki przedstawia zdarzenia sprzed roku, a zostanie namalowany za lat kilkadziesiąt. Generał Poniński (Michał Mrozek) jest jednocześnie bohaterem sztuki sprzed wieku, bohaterem dzisiejszego spektaklu, postacią historyczną i legendą o sobie samym.

fot. Bartosz MazPunktem wyjścia jest rok 1794, ale postacie znają fakty historyczne, jak również ich współczesne interpretacje. Zdają się też mieć pełną świadomość, co się stało przed, w czasie i po wojnie. Narracja toczy się w kilku czasach jednocześnie. Rosjanin Pałkin (Wojciech Ziemiański), przemierzając scenę z reprodukcją „Rejtana” pod pachą, wspomina, że obraz Matejki przedstawia zdarzenia sprzed roku, a zostanie namalowany za lat kilkadziesiąt. Generał Poniński (Michał Mrozek) jest jednocześnie bohaterem sztuki sprzed wieku, bohaterem dzisiejszego spektaklu, postacią historyczną i legendą o sobie samym. fot. Bartosz MazBrzyk i Śpiewak nie zatrzymują się jednak na politycznie poprawnych rewizjach pamięci. Dystansują się również wobec dzisiejszych zabiegów odkłamywania historii – zbyt łatwych i sentymentalnych, by były skuteczne. Na koniec serwują nam przewrotną demistyfikację. Oszukałem państwa – mówi Mrozek w ostatniej scenie – pan Aronowicz nie musiał wyjeżdżać w 68 do Izraela. Spał spokojnie pod swoją pierzyną do końca swoich dni.

fot. Bartosz MazBrzyk i Śpiewak nie zatrzymują się jednak na politycznie poprawnych rewizjach pamięci. Dystansują się również wobec dzisiejszych zabiegów odkłamywania historii – zbyt łatwych i sentymentalnych, by były skuteczne. Na koniec serwują nam przewrotną demistyfikację. Oszukałem państwa – mówi Mrozek w ostatniej scenie – pan Aronowicz nie musiał wyjeżdżać w 68 do Izraela. Spał spokojnie pod swoją pierzyną do końca swoich dni.