His career, however, started out differently. Leibowitz built up his criminal law practice defending petty crooks and mobsters. Over a period of 14 years, from 1919 to 1933, he boasted a track record of 77 acquittals in 78 murder trials, with one hung jury and no convictions. At that point, he was charging $10,000 per trial (worth about $150,000 to $230,000 today). By the time his law practice ended in 1940 when he was elected a county court judge—in 1962, he became a justice of the New York state Supreme Court—that trial record had increased to 140 men and women whom he had successfully defended on murder charges; only one of his clients, Salvatore Gati, had been executed, in January 1939 for killing a police officer during a robbery at a precious metals processing plant. Gati’s fingerprint had been identified on the gun that had killed the officer. Leibowitz had tried to extricate himself from the case when this became known, but the judge refused his request.

Leibowitz and his parents, Isaac and Bina (Jacobina), fled persecution and poverty in Romania, where he was born, and sought refuge in New York City in 1897. Samuel was then 4 years old. The family’s surname was Lebeau, but within a few years of coming to the United States, Isaac “Americanized” it to Leibowitz. They settled in the Lower East Side in a tenement on Essex Street among the multitude of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. At first, Isaac struggled to make a living as a peddler. But his perseverance paid off. Eventually, he was able to open his own dry goods shop in Harlem and then by 1906, a new store on Fulton Street in Brooklyn, where he was also able to purchase a house. Samuel’s early education and the skills he acquired during grade school in oratory and theater later were to serve him well as a lawyer.

As Diana Klebanow and Franklin L. Jonas note in their 2003 survey of Leibowitz’s career in People’s Lawyers: Crusaders for Justice in American History, his legal education began in 1911 at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Like other children of immigrants, he was diligent, studious, and achieved high grades. He had to work at a part-time job washing dishes in a school kitchen to make extra money. He was a member of the debate team and excelled as an actor; he was also the first Jewish student permitted to join the university’s dramatic society. His decision to seek a career in criminal law was based on his love of courtroom drama as well as his realistic assessment that no Manhattan corporate law firm would have hired a Jewish law graduate. The elitist dean of the law school, who regarded criminal law practice as insufficiently prestigious for his graduates, was not pleased with Leibowitz’s plan. “Not criminal law, Sam,” he exclaimed when Leibowitz informed him, “anything but that.”

Leibowitz’s career path was set, however. Starting out in 1916, he started working with several small firms, including one headed by Brooklyn attorney Michael McGoldrick, who had a lot of Irish Catholic clients. They liked Leibowitz, whom they referred to as “our Roman Jew.” Under McGoldrick’s tutelage, Leibowitz honed his research and brief-writing skills. In 1919, the year Leibowitz opened his own law office in Brooklyn—one of his first clients was a skilled pickpocket named “Izzy the Goniff” (or thief), who was acquitted—he married Belle Munves, the daughter of a Bronx pharmacist. Two years later, Belle gave birth to twin boys, Robert and Lawrence. A daughter, Marjorie, was born in 1926. By then, the family was living in a large home in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn.

The family’s surname was Lebeau, but within a few years of coming to the United States, Isaac ‘Americanized’ it to Leibowitz.

As Leibowitz once explained it: “My job as a criminal lawyer was to sell my client’s cause to the jury.” He did that superbly. He later said that he did not knowingly defend a guilty client, but he firmly believed that even crooked mobsters—“vultures of our society,” as he labeled them—were entitled to the best defense he could give them. He used, he said, “every ounce of ability” he possessed to achieve this. He and his assistant interviewed potential witnesses in each case they worked on, checking and rechecking facts. Before scientific jury selection (or trial science) was openly practiced during the 1970s, Leibowitz was a pioneering practitioner. He diligently studied each member of a particular jury pool and strategically used peremptory challenges to control as much as was possible the makeup of the jury under consideration.

Success in court was thus the result of hard work and meticulous research. In one of his most notable cases, he brilliantly convinced the jury of the innocence of Harry Hoffman, a young Jewish resident of Staten Island. In Hoffman’s first trial—in 1924, before Leibowitz was involved—he was convicted in the sexual murder of a 25-year-old housewife named Maude Bauer. Hoffman escaped the electric chair, but he was sentenced to life imprisonment. While he had not helped himself by initially lying to the police about his whereabouts as well as the fact that he owned a .25 caliber gun, the same type used in the crime, Hoffman claimed he was innocent.

Following an appeal three years later that led to two failed attempts at a retrial, Leibowitz agreed to become Hoffman’s lawyer. By that point, Hoffman had spent five years in jail. He had written to Leibowitz urging the lawyer to assist him, and Leibowitz answered his call. To prove Hoffman innocent, Leibowitz immersed himself in the intricacies of ballistics to refute the testimony of the prosecution’s gun experts that Hoffman’s revolver was the murder weapon. The murder of Maude Bauer was never officially solved. In other murder trials, Leibowitz pored over medical and psychology books in order to also cross-examine opposing expert witnesses and raise sufficient doubts about their testimonies.

Leibowitz innately grasped that he was part counsel and part showman; that winning over juries in high-stakes cases required him to not only poke holes in prosecutors’ arguments and expose weakness and flaws in the testimonies of prosecution witnesses—one of his favorite questions to trip up an opposing witness was: “Did you ever tell a lie in your life?”—but also to maintain the jury members’ undivided attention in cases that were often complicated and sometimes tedious. He achieved this by impressing them with his knowledge and expertise and by keeping them focused and entertained. “A criminal lawyer,” Leibowitz once conceded, “has to be a combination of a Belasco [David Belasco, a celebrated theatrical producer], a Barrymore, an Einstein, and an Al Smith [the outspoken governor of New York from 1919-20 and 1923-28].”

His voice was animated, gestures dramatic, and he did not hesitate to go after and even mock prosecutors and their witnesses; his quick wit always evident. “He laughs so heartily, so uncontrollably, that the jury usually joins him,” wrote Alva Johnston in a June 1932 New Yorker profile of Leibowitz. “He shakes, chokes, gasps, is speechless … A humorous sally at the wrong time may freeze up a courtroom and appal the jurors, but Sam has the instinct of an artist in timing his gags and guffaws.” It was not as if Leibowitz studied great defense lawyers of the past: He developed these essential skills innately, the result of his personality, intelligence, and instinctive understanding of human nature.

In late June 1928, Patrolman Thomas Fitzgerald was ordered to deal with a domestic disturbance at a home in Brooklyn. Once there, he allegedly confronted Vincenzo Santangelo, who had been accused of threatening his wife and her brother and mother who lived in a suite on the upper floor of the house. According to Charles Fauci, the wife’s brother, Santangelo had shot Fitzgerald, who was wounded. He then fled the scene.

The patrolman survived and Santangelo eventually turned himself in and was charged with first-degree assault. Leibowitz was hired to defend him at his trial held in April 1930. Santangelo’s alibi was that at the time of the shooting, he claimed he was working at a Manhattan fish market and not living with his family in Brooklyn. To prove Santangelo was lying, the assistant district attorney prosecuting the case brought into court a basket of freshly caught fish and asked Santangelo to identify them. He showed Santangelo the first piece and Santangelo said it was flounder. The next one, he said was butterfish; the one after that, bass. In fact, Santangelo could not correctly identify one of the half-dozen pieces of fish.

Leibowitz had a problem, yet he quickly recovered. Santangelo, he pointed out, worked at a fish market at 114th Street and Lexington that was known to serve Jewish customers. Of the fish that the prosecutor showed his client, argued Leibowitz, none of them was the type utilized in preparing gefilte fish. “My client is an Italian that works in a Jewish fish market,” Leibowitz declared in his summation to the jury, “and they try him on Christian fish.” The judge smirked and the jury members howled. A short while later, Santangelo was acquitted.

What Leibowitz understood and used to his advantage more than most defense attorneys during his heyday as a lawyer in the 1920s and ’30s was that members of the New York Police Department were ruthless and frequently corrupt, and had been for decades. There was near certainty that an uncooperative suspect in a murder investigation—or any felony, for that matter—in the custody of the NYPD without a lawyer present was given what was commonly referred to as the “third degree.” Suspects were routinely abused and even tortured until they confessed.

Leibowitz countered this “ends justified the means” distorted rationale with what he termed his “frameup defense.” All he had to hear was for a prosecutor to relate to a jury that the accused had “made a confession at police headquarters” and he instantly knew he had won the case. Merely insinuating that the police had crossed the line in interrogating the accused was usually sufficient to raise reasonable doubt.

In the spring of 1929, Leibowitz was defending three men arrested for robbing a Brooklyn theater. They had allegedly confessed their guilt to the police. The prosecutor believed his case against the men was solid. Then, in his closing remarks to the jury, Leibowitz declared that the men had been “night-sticked” into telling the police what they wanted to hear. It took a few hours and three ballots, but Leibowitz had got the men a verdict of “not guilty.”

Sometimes, Leibowitz wisely took preemptive actions in his dealings with the police. In 1925, in the midst of Prohibition, Al Capone, only 26 years old, was already in his prime as the country’s most notorious gangster, raking in millions of dollars from speak-easies, gambling, and brothels. On Christmas Day, Capone, who was based in Chicago, was visiting his mother in Brooklyn. Late that night, accompanied by a small group of local Italian mobsters, he attended what was supposed to be a friendly gathering with several members of the Irish White Hand gang. Yet when a White Hand tough insulted Capone, a shootout ensued in which three of the Irish mobsters were killed and one was severely wounded.

Soon after, the police issued arrest warrants for Capone and several of the Italian American gangsters. The next day there was a knock on the door of Leibowitz’s home and 4-year-old Robert ran to open it. Standing on the stoop was Capone and his henchman Frank Nitti, who told the boy that they were there to meet with his father. They wanted Leibowitz to represent them. He agreed to do so. Anticipating that the gangsters would be beaten into confessing their crime—the police also referred to this treatment as “massaging” a suspect—if they surrendered to the authorities, Leibowitz had each man photographed naked, back and front, and had the photographer sign an affidavit attesting that he had taken the pictures that day. He then made a deal with a Brooklyn police captain to turn over Capone and the other men, but only if they were immediately arraigned.

“I am handing over these men in good shape,” Leibowitz told the captain. “They have been examined by a witness and there are no marks upon their persons. You don’t dare ‘massage’ them.” That strategy worked; Capone and the other gangsters were not roughed up. And, they beat the murder charges. Leibowitz secured a statement from the Irish gangster, who had been wounded and was recovering in the hospital, that he had been shot by strangers and not by Capone and his men. A dinner was held to celebrate their release at which Leibowitz was toasted with cries of “Viva Leibowitz.” For years after Leibowitz received holiday fruitcakes from Capone signed “Your pal, Al.”

Though Leibowitz believed that Capone and the other mobsters he represented over the years were entitled to a competent defense like anyone else charged with a crime, he was never entirely comfortable with his publicized association with them. “I never consorted with them in the first place,” he once remarked about his former clients. “They never slapped me on the back and called me ‘Sam.’ I looked upon them as a doctor would a case.” Later, he refused a $250,000 retainer, an exorbitant sum in the 1930s, to serve as counsel for Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, one of the heads of Murder, Inc., an organized mob hit squad. Buchalter was executed at Sing Sing prison on March 4, 1944.

‘Show them,’ he told the all-white jury members, ‘that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York.’

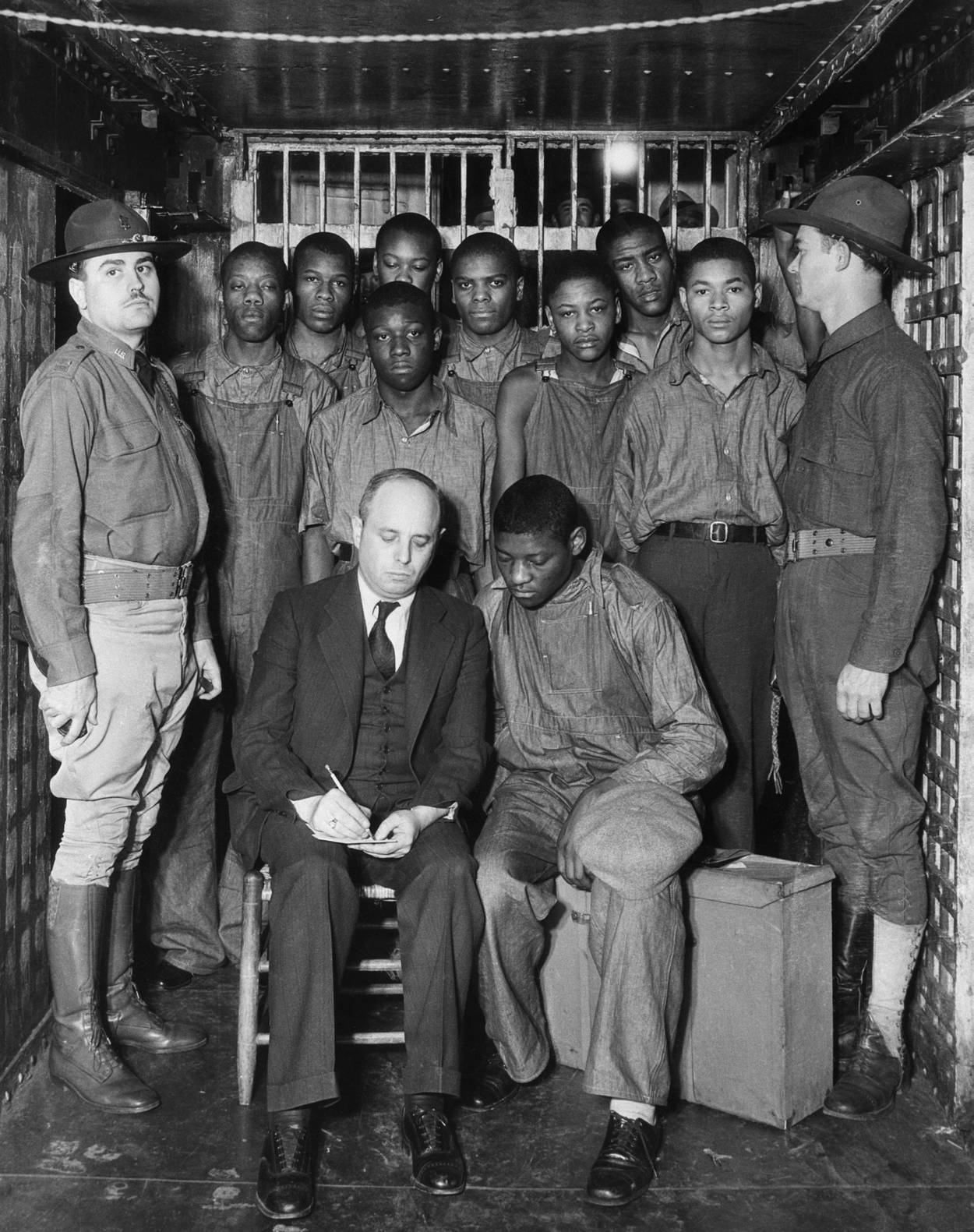

The most important case of Leibowitz’s career, and one that solidified his stature as a champion of the underdog and human rights and enhanced his reputation far beyond New York City, began for him in Alabama in 1933. Two years earlier, in a miscarriage of justice that was all too typical in the segregated South, nine young African American men, who ranged in ages from 12 to 19, were convicted in trials held in the town of Scottsboro, Alabama (about 100 miles north of Birmingham) for allegedly raping two white girls, Victoria Price, 21, and Ruby Bates, 17, aboard a freight train traveling through Alabama on its way to Memphis. The “Scottsboro Boys,” as they became known (only four of them knew each other) also had fought with several young white men who had been on the train. The white teenagers, who had lost the fight, then reported this altercation to the police after they hopped off the train—the start of the Scottsboro Boys’ legal nightmare. The nine claimed they were innocent of raping the two girls, and they were. But all of them—except 12-year-old Roy Wright, who was granted a mistrial—were sentenced to death. (Considering that 299 African Americans were lynched in Alabama from 1882 to 1968, “the fact that the [young men in Scottsboro] were not immediately lynched,” lawyer Alan Dershowitz has written, “demonstrated some degree of progress …”)

The two girls had concocted the story about the rape to avoid getting in trouble for vagrancy and having illegal sexual relations. Early in 1932, a letter from Ruby Bates to a boyfriend was made public in which she denied having been raped. Nonetheless, a few months later the Alabama Supreme Court in a 6-to-1 vote upheld the convictions of seven of the defendants (the conviction of 13-year-old Eugene Williams was reversed because he was a juvenile in 1931). In November 1932, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned that ruling and deemed that the defendants were denied their right to counsel, which violated their right to due process under the 14th Amendment. The cases were remanded to the lower court, which meant new trials had to be held. In January 1933, the International Labor Defense, an organization with ties to the Communist Party, recruited Leibowitz to take charge of the defense in the new trials.

“I shall remain active in this cause as long as there is a breath of life in me,” Leibowitz told a writer from the Jewish Daily Bulletin. “It is not the cause of the Negro alone, it is the cause of my own people!” He added, “What a glorious opportunity it was for the lot to fall to a Jew to strike a blow for the emancipation of the colored race! … Believe me, I’ll do all in my power to reflect credit on my people in the fight we’re waging.” He also no doubt recognized that participating in such widely covered legal proceedings and championing African Americans’ legal rights would “add to the realm of his renown,” as his son Robert later wrote.

It was a protracted fight. For more than five years, Leibowitz battled witnesses who openly lied. While Ruby Bates eventually recanted her testimony, Victoria Price refused to do so for the rest of her life. Leibowitz’s cross-examination of Price was especially harsh, but he felt it necessary to expose her lies. He faced racist judges and prosecutors, confronted illegal court procedure rulings, and regularly received death threats. During the first of several trials, speakers at rallies near the Jackson County courthouse inflamed the crowd who called for the young men to be lynched and Leibowitz and other lawyers assisting him to be tarred and feathered. A pamphlet circulated with the title “Kill the Jew From New York.” In his summation to the jury, assistant prosecutor County Solicitor Wade Wright made no attempt to hide his antisemitism. “Show them,” he told the all-white jury members, “that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York.”

In the end, it was a bittersweet legal victory for Leibowitz, who eventually had had enough. Not one to lose his temper in front of a jury, he declared during one of the final trials that he was “sick and tired of the sanctimony and hypocrisy of the state and people of Alabama.” Back in New York, he was hailed for standing up to Southern bigotry.

In February 1935, Leibowitz appeared before the Supreme Court; it was the first and single time he ever did so. He ultimately won a ruling when the court found that the exclusion of African Americans on Alabama jury rolls—despite assertions to the contrary by Jackson County officials—deprived Black defendants of their rights to equal protection under the law as guaranteed in the 14th Amendment. Though in subsequent trials in Scottsboro and throughout the South, unscrupulous legal officials attempted to get around the law, they were unable to prevent African Americans from serving on juries, especially in cases with African American defendants. That ruling was rightly part of Leibowitz’s legacy. At the same time, and notwithstanding the ruling in his favor by the U.S. Supreme Court and Leibowitz’s best efforts, several of the Scottsboro Boys were convicted and served prison time until Alabama state officials were prepared to concede that they had indeed incarcerated innocent men. The lives of each were changed forever by hate and false testimony. It took more than eight decades, until November 2013, for Alabama’s parole board to grant posthumous pardons for the three remaining “Scottsboro Boys” who still had not had their convictions rescinded.

Seeking other professional opportunities, Leibowitz, a loyal Democratic Party member, accepted the nomination in 1940 for judge of the Kings County Court, a criminal court that always had more cases than it could process. He comfortably won the election and began a 14-year term. Though toying with the idea of running for mayor of New York City, he was reelected as a judge in 1954 for a second term. Then, following a restructuring of the courts in New York City in 1962, he was named a justice of the New York State Supreme Court, where he served until his retirement seven years later.

From the start of his deliberations, Judge Leibowitz was tough and unrelenting in his determination to ensure that the cause of justice was properly served—at least, as he interpreted it. “He used the same eloquence,” The Washington Post later noted, “with which he once had persuaded juries to return verdicts of ‘not guilty’ to berate prosecutors, defense attorneys, police officers, defendants, and, sometimes, other judges.” He had little sympathy for those found guilty of committing a crime, no matter their age or the circumstances. Punishment was meted out accordingly. Leibowitz had utilized a fair number of clever strategies as a defense lawyer, yet as a judge he roughly chided another defendant for refusing to answer his questions. “I’ll give you a thousand years, if necessary,” he warned the man.

He presided over more than 11,000 trials—of notorious gang members and organized crime assailants, ordinary men and women, as well as New York celebrities such as Leo “the Lip” Durocher, the famed and ornery baseball player and manager. In June 1945, Durocher, then the manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, was arrested at Ebbets Field along with John Moore, a special policeman, for assaulting a fan named John Christian who had heckled Durocher throughout the game. In the fight, Christian’s jaw was fractured. In a trial held before Leibowitz the following April, the jury acquitted both defendants in 38 minutes.

Durocher was lucky. Earning the nickname “Sentencing Sam,” Leibowitz dispensed harsh—but in his view, fair and just—punishment to convicted felons, including the death penalty, which he long maintained acted as a deterrent. So it was that in mid-February 1941, the lawyer who had saved more than 100 clients from the electric chair imposed his first death sentence on George Zeitz, a 25-year-old laborer from Brooklyn who had been convicted of murdering a loan shark named Irving Moskowitz following a dispute about an unpaid loan. During Leibowitz’s almost-30-year career on the bench, he sent 40 defendants to the death house at Sing Sing and other institutions.

Still, the compassion that Leibowitz had shown as an attorney remained part of his psyche. He was an early prison reformer, supporting conjugal visits for inmates. He also pushed for programs to rehabilitate juvenile delinquents. And, early in January 1944, he appointed the first African American—not only in the state of New York but in the entire country—to serve as foreman of a grand jury.

In the early 1950s, Leibowitz was again on the front pages of New York newspapers with his supervision of a grand jury that issued indictments against 18 New York City policemen who were accused of taking bribes from bookmaker Harry Gross. In the subsequent trial, Gross refused to testify and Leibowitz cited him for contempt 60 times and sentenced him to five years in prison and a $15,000 fine. Soon after, Leibowitz testified in Washington, D.C., and shared his knowledge of bookmaking and gambling with members of the U.S. Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce—or Kefauver Committee—chaired by Sen. Estes Kefauver (the committee was immortalized in the film Godfather II).

Leibowitz became testier as he became older. He was accused by lawyers and judges of having a bad temper in court. Yet, he did not want to retire at the mandatory retirement age of 70 in 1963. He got a reprieve from a board of his fellow judges who certified him as fit for continued service, despite the fact that the Association of the Bar of the City of New York opposed his redesignation to the bench. He remained a judge for another six years, until 1969. In an emotional ceremony in his courtroom on his last day, with his wife, Belle, and his children present, Leibowitz, fighting tears, said, “They spoke of me as a tough judge. Well, [my wife] can tell you how nights went by when I tossed in bed until dawn trying to figure out what to do with the poor devil to be sentenced in the morning.”

Nine years later, on Jan. 11, 1978, the legendary Samuel Leibowitz died in a Brooklyn hospital following a stroke. He was 84 years old.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.

Ferie w ŻIH 2024

Ferie w ŻIH 2024.webp)