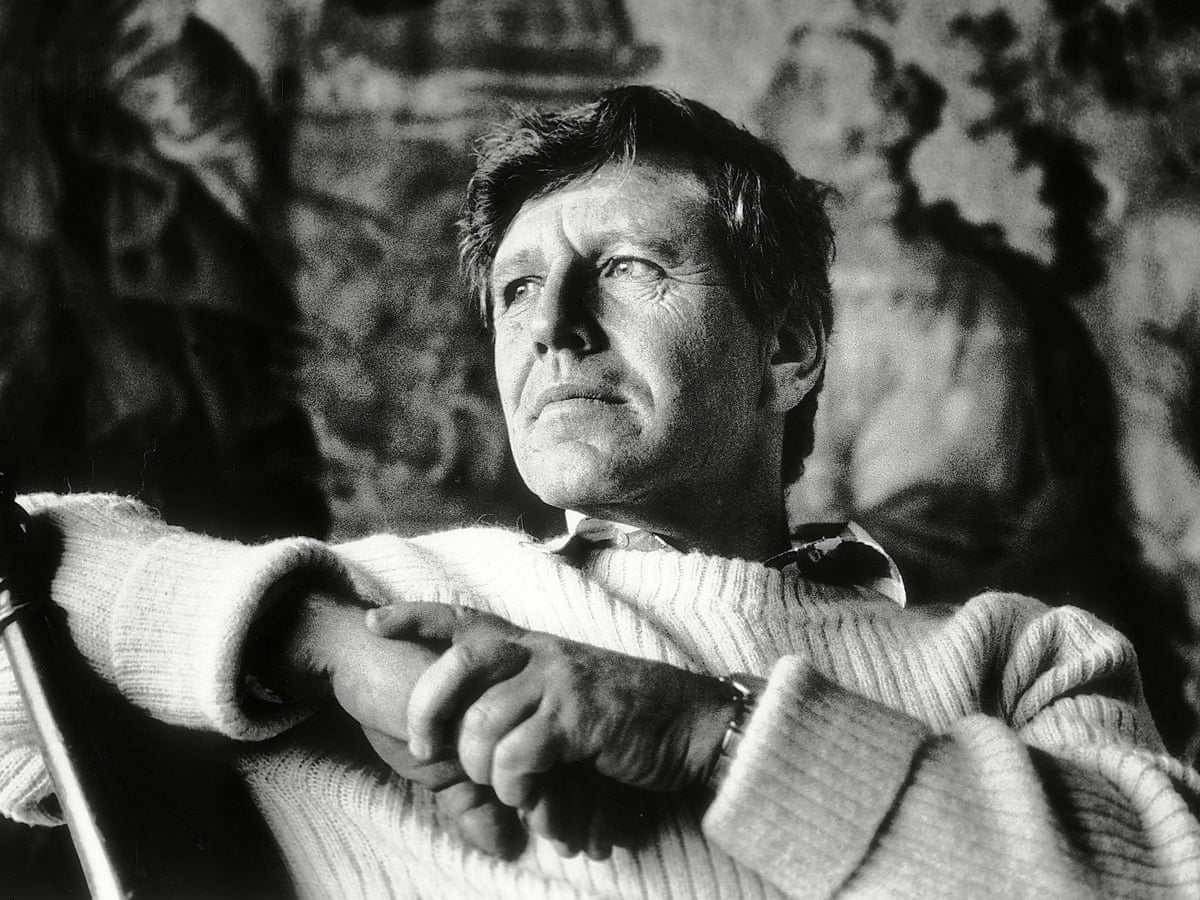

Przeciwieństwem kompromisu jest fanatyzm i śmierć”… Amos Oz, zdjęcie z 1989 roku. Zdjęcie: Tom Pilston/The Independent/Rex/Shutterstock

Przeciwieństwem kompromisu jest fanatyzm i śmierć”… Amos Oz, zdjęcie z 1989 roku. Zdjęcie: Tom Pilston/The Independent/Rex/Shutterstock

CZAROWNIK SWOJEGO PLEMIENIA

CZAROWNIK SWOJEGO PLEMIENIA

BARTOSZ STASZCZYSZYN

Książki Amosa Oza to nie tylko narodowe dramaty, wojna, religia i szalone ideologie. To opowieść o zwykłych ludziach, ich niezabliźnionych ranach i życiowych wybojach

.

Amos Oz lubi rozczarowywać. Zwłaszcza tych, którzy postrzegają go przez pryzmat prasowych wywiadów i obiegowych opinii. Oglądany z tej perspektywy izraelski pisarz wydaje się twórcą skończonym: wielkim, mądrym, znającym najważniejsze odpowiedzi. Koturnowym. Jest pacyfistą-bojownikiem, założycielem organizacji „Pokój teraz” i uniwersyteckim wykładowcą. Jest pewny siebie, potężny.

Ale Amos Oz ma także drugą twarz – wrażliwca, osamotnionego myśliciela, który ma w sobie wiele niepewności. Oz-pisarz zadaje pytania, chwyta świat i próbuje zamknąć go w literackiej klatce, ale czasem po prostu chce opowiedzieć historię. Bo autor „Fimy” jest także bajkopisarzem, gawędziarzem o filozoficznym zacięciu. Jest pisarzem zwyczajnym, a przez to całkowicie niezwykłym. Skromnym i dzięki temu – wielkim.

Izrael jest powieścią

Dowodem jego literackiego kunsztu są m.in. „Sceny z życia wiejskiego”, tom opowiadań wydanych właśnie po polsku. W ośmiu krótkich historiach pisarz zabiera nas do świata, którego nie ma. Zapewne nigdy nie było – bo życie w Tel Ilan jest cokolwiek nierzeczywiste. Wioska założona przez żydowskich osadników przypomina Eden – świat pełen harmonii, ale też tajemniczy. To tutaj mieszkają bohaterowie Oza. W magicznym, ulotnym świecie Tel Ilan rozgrywają się dramaciki samotnej lekarki i pięknej wdowy, młodego Araba i mężczyzny tracącego głowę dla urodziwej dziewczyny. Podobnych postaci jest tutaj więcej, wszystkie zaś osnute są aurą sekretności.

W małej żydowskiej wiosce życie podporządkowane jest dziwnemu, na poły magicznemu porządkowi. Przeznaczenie pląta ludzkie losy, zderza ze sobą przeciwieństwa, każe bohaterom rozwiązywać gordyjskie węzły życia. W tych opowiadaniach autor zabiera nas bowiem do świata nierzeczywistego, ale prawdziwego. Mówiąc o fikcyjnej rzeczywistości, dyskretnie dotyka tajemnic życia. Jest taktowny – nie sili się na żadne diagnozy, nie stawia fundamentalnych pytań, ba, jego opowiadania pozbawione są point. Te proste opowieści ukazują Oza mniej znanego, pisarskiego uwodziciela, który broni się siłą języka, nie zaś atrakcyjnością politycznych tematów.

W małej żydowskiej wiosce życie podporządkowane jest dziwnemu, na poły magicznemu porządkowi. Przeznaczenie pląta ludzkie losy, zderza ze sobą przeciwieństwa, każe bohaterom rozwiązywać gordyjskie węzły życia. W tych opowiadaniach autor zabiera nas bowiem do świata nierzeczywistego, ale prawdziwego. Mówiąc o fikcyjnej rzeczywistości, dyskretnie dotyka tajemnic życia. Jest taktowny – nie sili się na żadne diagnozy, nie stawia fundamentalnych pytań, ba, jego opowiadania pozbawione są point. Te proste opowieści ukazują Oza mniej znanego, pisarskiego uwodziciela, który broni się siłą języka, nie zaś atrakcyjnością politycznych tematów.

Stefan Bratkowski pisał niegdyś o Ozie, że on sam jest „powieścią tak jak powieścią jest państwo Izrael”. Trafił w sedno. W książkach Izraelczyka to, co prywatne, spotyka się z tym, co publiczne. Osobiste rozterki są częścią narodowego dramatu, a intymne zwierzenia bohaterów opisują w istocie najbardziej charakterystyczne postawy społeczne. Zapewne dlatego często mówi się o literaturze Oza jako sztuce politycznie zaangażowanej, antywojennej, będącego głosem na rzecz pokoju na Bliskim Wschodzie.

Wojna, religia, fundamentalizm stanowią w twórczości Oza oś zła. Pisząc o ludziach mieszkających w Izraelu, autor „Fimy” kreśli obraz świata pogrążonego w nieustannym konflikcie, nękanego wojennym lękiem. Tutaj śmierć jest czymś codziennym, a zamachy bombowe i rakietowe ostrzały stanowią niemal integralną część krajobrazu. Jego bohaterowie rozdarci są między poczuciem obowiązku wobec państwa i narodu a powinnościami wobec samych siebie. Jak David, bohater „Poznać kobietę”, postaci Oza muszą sprzeciwiać się wizji świata narzucanej przez społeczeństwo. Są zakleszczone w szczękach sprzecznych ideologii, w ciasnych politycznych doktrynach i partykularnych interesach. Wojna jest bowiem doświadczeniem wypalającym – pozbawia indywidualizmu, zamieniając go na plemienną solidarność.

Oz zna tę rzeczywistość. Sam brał udział w wojnie sześciodniowej i Jom Kippur. W licznych wywiadach wspominał, że wiele lat po tamtych wydarzeniach budził się w nocy, czując odór wojny łączący w sobie zapach palonych ciał, metalu i płonącej gumy. Ale dramatyczne wydarzenia z młodości autora „Czarnej skrzynki” nie uczyniły go wcale niepoprawnym idealistą. Oz mówi o sobie: „Nie jestem pacyfistą i nie nadstawiam drugiego policzka”. Właśnie dlatego popierał akcję odwetową prowadzoną w Strefie Gazy po tym, jak na miasta i wioski żydowskie przez lata spadały rakiety Hamasu. Oz wie, że wojna bywa polityczną koniecznością, a najważniejsze jest to, by nawet w jej czasie nie przekraczać granic człowieczeństwa.

Oz zna tę rzeczywistość. Sam brał udział w wojnie sześciodniowej i Jom Kippur. W licznych wywiadach wspominał, że wiele lat po tamtych wydarzeniach budził się w nocy, czując odór wojny łączący w sobie zapach palonych ciał, metalu i płonącej gumy. Ale dramatyczne wydarzenia z młodości autora „Czarnej skrzynki” nie uczyniły go wcale niepoprawnym idealistą. Oz mówi o sobie: „Nie jestem pacyfistą i nie nadstawiam drugiego policzka”. Właśnie dlatego popierał akcję odwetową prowadzoną w Strefie Gazy po tym, jak na miasta i wioski żydowskie przez lata spadały rakiety Hamasu. Oz wie, że wojna bywa polityczną koniecznością, a najważniejsze jest to, by nawet w jej czasie nie przekraczać granic człowieczeństwa.

Fundamentalizm jest jeden

Izraelski prozaik zdaje sobie też sprawę, że to nie kule są najgroźniejszym narzędziem wojny, ale ideologia. W jego powieściach najbardziej przerażają potulni ekstremiści. Jak Michel w „Czarnej skrzynce”, ciepły facet o radykalnych przekonaniach, który ledwie może utrzymać rodzinę, ale co miesiąc przelewa znaczną kwotę na konto Ruchu Wspólnoty Żydowskiej. Wierzy, że „Żyd bez Tory jest gorszy od dzikiej bestii”, a ziemie należące do potomków Mojżesza powinny wrócić w ich ręce. W powieściach Oza to właśnie ludzie zaślepieni, zbyt pewni własnych racji, są największym zagrożeniem. Oni nakręcają spiralę zbrojnego konfliktu. W eseju z tomu „Czarownik swojego plemienia” Oz pisze: „konfrontacja między Żydami powracającymi do Syjonu a arabskimi mieszkańcami nie przypomina westernu ani eposu, bardziej tragedię grecką. Jest to konflikt prawa z prawem (…) nie ma nadziei na szczęśliwe pojednanie”.

W świecie przeciwstawnych fundamentalizmów nie ma miejsca na pojednanie i pokój. Radykałowie po obu stronach barykady wzajemnie się wspierają; ścierając się ze sobą, dostarczają sobie nowych racji. W wywiadzie udzielonym Pawłowi Smoleńskiemu pisarz mówił wprost: „Fundamentalizm jest jeden. Różni się kolorem, ale nie sposobem myślenia”. O niszczącym wpływie ideologii, o zaślepieniu i nienawiści opowiada także w swych książkach. Jej destrukcyjnemu urokowi poddają się m.in. bohaterowie nowel wydanych w tomie „Aż do śmierci” – dowódca wyprawy krzyżowej i Żyd ogarnięty antyrosyjską obsesją. Mówiąc o ludziach omamionych przez ideologie, Oz mówi o duszy współczesnego Izraela. Jego tematem nie są żydowsko-arabskie spory i religijna wojna.

W świecie przeciwstawnych fundamentalizmów nie ma miejsca na pojednanie i pokój. Radykałowie po obu stronach barykady wzajemnie się wspierają; ścierając się ze sobą, dostarczają sobie nowych racji. W wywiadzie udzielonym Pawłowi Smoleńskiemu pisarz mówił wprost: „Fundamentalizm jest jeden. Różni się kolorem, ale nie sposobem myślenia”. O niszczącym wpływie ideologii, o zaślepieniu i nienawiści opowiada także w swych książkach. Jej destrukcyjnemu urokowi poddają się m.in. bohaterowie nowel wydanych w tomie „Aż do śmierci” – dowódca wyprawy krzyżowej i Żyd ogarnięty antyrosyjską obsesją. Mówiąc o ludziach omamionych przez ideologie, Oz mówi o duszy współczesnego Izraela. Jego tematem nie są żydowsko-arabskie spory i religijna wojna.

Oza interesuje żydowska tożsamość i samo państwo Izrael, ta wielka psychologiczna powieść pisana od sześćdziesięciu dwóch lat. Autor „Mojego Michaela” odczytuje ją z zaciekawieniem i jednoczesnym przerażeniem. W jednym z wywiadów mówił: „Izrael musi rozczarowywać, bo to państwo, które powstało z marzeń. A to, co rodzi się z marzeń, zawsze jest rozczarowaniem. Do tego Izrael nie jest owocem jednego marzenia, lecz syntezą wielu”. Na Bliskim Wschodzie wszyscy mają swoją wizję świata i swoją rację. Analizując żydowski mesjanizm i pełen samoudręczenia kult Shoah, Oz dostrzega, że w Izraelu „prawie wszyscy uważają się za potencjalnych premierów czy Mesjaszy”.

Starcie żywiołów

Wielkie tematy, filozoficzne pytania i globalne problemy zajmują w twórczości Oza miejsce niepodważalne. Nie da się o nich zapomnieć, nie sposób nie usłyszeć rozpaczliwego nieraz głosu pisarza patrzącego na współczesny świat. Warto jednak czytać jego opowiadania i powieści także na innym poziomie. Oz jest bowiem jednym z najbardziej wrażliwych znawców ludzkich dusz, a jego książki – spojrzeniem do wnętrz bohaterów, obrazem egzystencji prozaicznej i zarazem doniosłej.

Mówiąc o swoich bohaterach, Oz często odrywa od nich wzrok, by wyjrzeć przez okno i podpatrywać zwyczajnych ludzi. Przygląda się sprzedawcy warzyw przestawiającemu skrzynki, handlarzowi nafty, starej pannie, która co dzień kilkakrotnie zamiata chodnik przy swojej kamienicy. Dopisując historie ich życia, splata poruszający obraz żydowskiego społeczeństwa, kolorową mozaikę ludzkich typów.

Tym, co zajmuje go równie mocno jak polityka, są międzyludzkie związki. Zwłaszcza zaś relacje damsko-męskie, raz podobne do strategicznej gry, innym razem – do walki żywiołów. Autor „Czarnej skrzynki” otwarcie przyznaje, że kobieca psychika jest dla niego jedną z największych tajemnic. W powieściach i w prasowych wywiadach przypomina często rozmowę, jaką odbył ze swym dziadkiem, wytrawnym kobieciarzem, który jako 92-latek uwiódł o połowę młodszą „lolitkę”. Swego dorosłego już wnuka pouczał: „Widzisz, chłopcze, kobiety są w pewnym sensie takie same, jak my. W innym zaś sensie są całkiem odmienne. Ale pod jakim względem są takie same, a pod jakim inne – tego właśnie wciąż staram się dociec”.

Tym, co zajmuje go równie mocno jak polityka, są międzyludzkie związki. Zwłaszcza zaś relacje damsko-męskie, raz podobne do strategicznej gry, innym razem – do walki żywiołów. Autor „Czarnej skrzynki” otwarcie przyznaje, że kobieca psychika jest dla niego jedną z największych tajemnic. W powieściach i w prasowych wywiadach przypomina często rozmowę, jaką odbył ze swym dziadkiem, wytrawnym kobieciarzem, który jako 92-latek uwiódł o połowę młodszą „lolitkę”. Swego dorosłego już wnuka pouczał: „Widzisz, chłopcze, kobiety są w pewnym sensie takie same, jak my. W innym zaś sensie są całkiem odmienne. Ale pod jakim względem są takie same, a pod jakim inne – tego właśnie wciąż staram się dociec”.

Podobne dociekania znajdujemy w prozie Oza. Jego kobiety to istoty fascynujące i tajemnicze. Choć są władcze, same potrzebują władzy, która je ujarzmi. Hanna, bohaterka debiutanckiej powieści Oza – „Mojego Michaela” – jest zamknięta w kokonie codzienności. Studentka literatury, która poświęca własne ambicje, by spełnić się mogły zawodowe plany jej ukochanego, nie bez przyczyny nazwana została „żydowską panią Bovary”. Snując swoją opowieść, Hanna uzmysławia sobie, że jej życie niepostrzeżenie rozsypuje się, kruszeje. Znudzona, smutna kobieta jest postacią tyleż tragiczną, co zwyczajną. Ilana ze świetnej „Czarnej skrzynki” wyszła za mąż za grzecznego mężczyznę, lecz wciąż marzy o kimś, kto nią zawładnie, zostając „panem jej nienawiści i tęsknoty”. Takie właśnie są kobiety Oza – nieprzeniknione.

Nieporadni mężczyźni

Dylematy i miłosne rozterki nieobce są także męskim bohaterom. Na tym jednak kończą się międzypłciowe podobieństwa – mężczyźni Oza to ludzie przyziemni, małostkowi i nieporadni. Choćby Fima, bohater jednej z najgłośniejszych powieści Izraelczyka, jakby nakreślony według archetypowego obrazu intelektualisty: źle zorganizowanego, niesamodzielnego i gubiącego się w rzeczywistości. Mężczyźni Oza budzą współczucie. Nostalgiczni i refleksyjni, są zaangażowani w politykę, mają wykształcenie, poglądy i ideologiczny kręgosłup. Rzadko rozumieją jednak samych siebie. Jak Joel Ravid – bohater „Poznać kobietę” – były szpieg, który po śmierci żony próbuje zrekonstruować własną tożsamość, na nowo określić zagubioną gdzieś osobowość.

Przyglądając się postaciom z kart powieści Oza, czasem trudno oprzeć się wrażeniu, że są one alter ego samego autora. Ironiczne, czasami kąśliwe portrety mają w sobie coś z autokarykatury mężczyzny, intelektualisty, człowieka politycznie zaangażowanego. Pisząc o nich, Oz pisze zarazem o sobie, o człowieku wychowanym na filmach z Humphreyem Bogartem i Garym Cooperem, który mierzy się z wzorcem mężczyzny, z wyzwaniami kultury, społeczeństwa, kobiet. Dla Oza bowiem sztuka nie jest ucieczką od rzeczywistości, ale jej zgłębianiem, przekładaniem jej na inny, bardziej usystematyzowany język.

Przyglądając się postaciom z kart powieści Oza, czasem trudno oprzeć się wrażeniu, że są one alter ego samego autora. Ironiczne, czasami kąśliwe portrety mają w sobie coś z autokarykatury mężczyzny, intelektualisty, człowieka politycznie zaangażowanego. Pisząc o nich, Oz pisze zarazem o sobie, o człowieku wychowanym na filmach z Humphreyem Bogartem i Garym Cooperem, który mierzy się z wzorcem mężczyzny, z wyzwaniami kultury, społeczeństwa, kobiet. Dla Oza bowiem sztuka nie jest ucieczką od rzeczywistości, ale jej zgłębianiem, przekładaniem jej na inny, bardziej usystematyzowany język.

Autor „Rymów życia i śmierci” wie, że sztuka jest grą wyobraźni wijącej się między rzeczywistością i fantazją. To także sposób na zmierzenie się z własnym bytem. W pisaniu powieści – mówi Oz – mam nieuczciwego konkurenta: samo życie. Ta walka może nie jest uczciwa, ale bardzo stymulująca. W swych powieściach Oz przygląda się bowiem światu, zaczynając od samego siebie. Kreśli autoportret artysty w różnych stadiach życia.

W genialnej „Opowieści o miłości i mroku” pisał zgryźliwie: „napalony dziennikarz i kiepski czytelnik zawsze chcą się dowiedzieć, w jakiej mierze fabuła zawiera wątki autobiograficzne”. Nie znaczy to wcale, że nie warto czytać literatury Oza jako monumentalnej autobiografii rozpisanej na pojedyncze tomy. W jego powieściach powracają wciąż te same wspomnienia: samobójcza śmierć matki, zmiana nazwiska, opuszczenie ojca i późniejsze życie w kibucu.

Ale od podobieństwa losów bohaterów i autora w literaturze izraelskiego prozaika ciekawsza jest jego autobiografia intelektualna – dialog pisarza, który podważa własne sądy, konfrontuje ze sobą różne punkty widzenia, by lepiej pojąć otaczający go świat, polityczną i społeczną przestrzeń Izraela. Piękne jest to zmaganie się z własnym umysłem, wojna myśli ukryta pod warstwą pozornie banalnych fabuł. Dzięki mądrości i skromności Oza jego książki niosą ukojenie i zarazem rzucają wyzwanie. Warto je przyjąć, by obcować z pisarzem tak znakomitym jak Amos Oz.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com