Serce nie sadysta, kiedyś przestanie bić

Serce nie sadysta, kiedyś przestanie bić

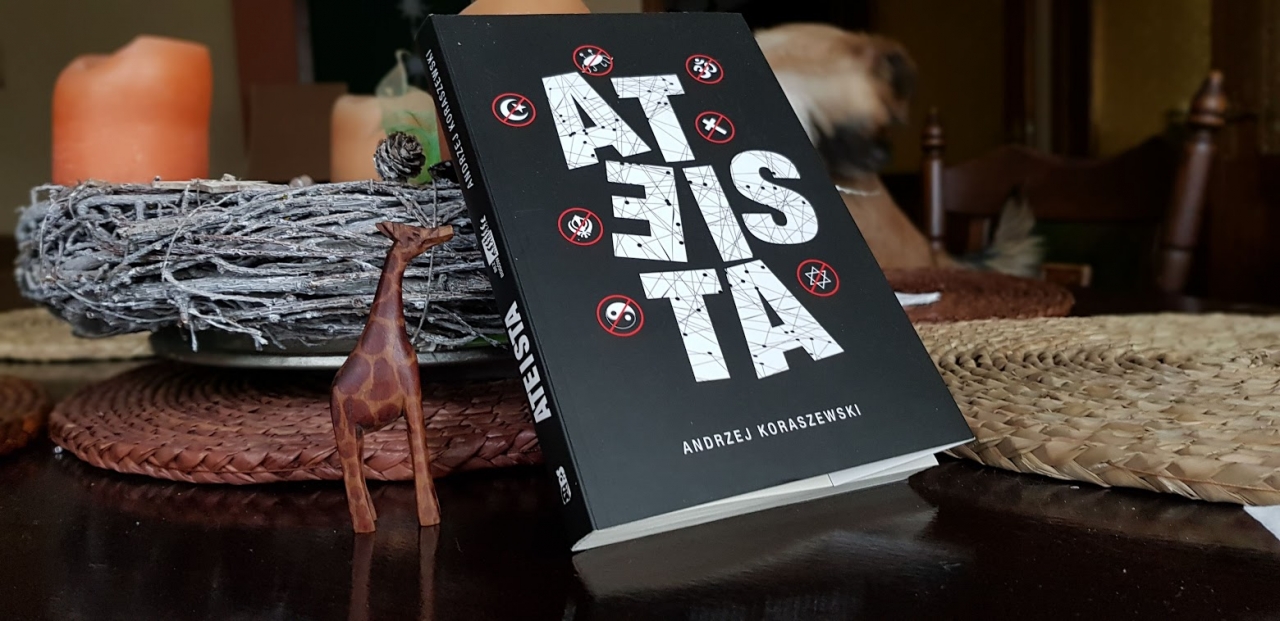

Andrzej Koraszewski

Dzwonek do bramy, odrywam się od korekty tłumaczonego artykułu i idę zobaczyć, kogo bogi przyniosły. Przed bramą znalazłem parę sympatycznie wyglądających młodych ludzi z małym, może sześcioletnim, a może siedmioletnim chłopcem. Mężczyzna podaje mi ulotkę. Nie muszę jej studiować. Świadkowie Jehowy chcą mnie przekonać do studiowania Biblii. Uśmiecham się przyjaźnie i informuję, że jestem ateistą. Mężczyzna chce się dowiedzieć dlaczego, więc odpowiadam, że próbuję być życzliwy dla innych nie ze względu na zagrożenie wieczystą karą piekła, a dlatego, że warto być przyzwoitym.

Kobiet uśmiecha się ciepło, mężczyzna kręci głową, a chłopczyk przestępuje z nogi na nogę.

Wyjaśniam, że zajmuję się nauką, a ta mówi, że prawdopodobieństwo istnienia istot nadprzyrodzonych jest mikroskopijne.

Mężczyzna pyta jaką nauką się zajmuję.

– Długa historia, studiowałem socjologię, ale socjologia jest podobna do teologii, dużo w niej spekulacji, niczego nie daje się udowodnić.

Stojąca obok męża kobieta parska śmiechem, mężczyzna nie daje za wygraną i zapewnia że Bóg jest. Chce wiedzieć czym dokładniej się zajmuję. Mówię, że studiowałem socjologię, od socjologii uciekłem do historii ekonomii, historia ekonomii jest spleciona z historią religii, historia religii jest spleciona z ewolucją…

– No właśnie, ewolucja, ucieszył się stojący za bramą potężny mężczyzna, którego iloraz inteligencji oceniałem na oko na 105. – Kiedy znajdzie pan na plaży szklaną butelkę…

Przerywam mu i mówię, że ta butelka, to zapewne zegarek na wrzosowisku, bardzo stary argument o skomplikowanym przedmiocie, który musiał być przez kogoś zrobiony. Wie pan, w dzieciństwie słyszałem dowcip o tym jak nauczycielka powiedziała, że szkło robi się z piasku, Jaś się zdumiał, ale kolega z ławki szepnął mu na ucho, żeby się nie martwił, że nauczycielka musi tak mówić, bo jej ci komuniści tak każą.

Głośny wybuch śmiechu młodej kobiety mógł wskazywać na iloraz inteligencji w granicach 120. Chłopczyk nadal przestępował z nogi na nogę.

Wyjaśniam mężczyźnie, że jak znajdzie nieoszlifowany diament, to nie będzie się zastanawiał nad tym, kto go zrobił.

Mężczyzna postanowił zmienić temat.

– Czyli wierzy pan w wielki wybuch…

– Wie pan – odpowiedziałem – w nauce nie ma wiary. Mamy dowody, które mogą okazać się błędne lub niepełne. Nauka to taki legoland, budujemy z klocków, które mamy i szukamy klocków, których nam brakuje.

Chłopczyk podniósł głowę z ciekawością.

– W religii – mówiłem dalej – próbujemy umocnić to, w co wierzymy, w nauce próbujemy podważyć to co nam się zdaje, że jest prawdą, żeby zostało to, czego podważyć się nie da.

– Więc nauka się myli – ucieszył się mężczyzna.

– Oczywiście, że nauka się myli, to jest nieustający spór, gromadzenie dowodów, korygowanie błędów, nauka jest ludzka, nie ma w niej nic boskiego.

– Ludzki umysł jest boski, został stworzony przez Boga, człowiek może uprawiać naukę, bo jest istotą myślącą, jest Homo sapiens.

– To prawda mamy duży mózg, ale nie tak sprawny jak nam się wydaje. Jest taka teoria, że ten duży mózg zawdzięczamy dziewczynom, że jest jak ogon pawia, służył początkowo głównie do popisów. To wszystko przez baby, łatwiej je było uwodzić śpiewem, ładnymi ozdobami, malunkami, panie wybierały jaskiniowych celebrytów i potem rodziły dzieci z coraz większymi główkami. Ten pomysł z biblijną Ewą wcale nie jest taki odległy od prawdy, tyle, że to nie było jabłko.

Kobieta zachichotała, mężczyzna spojrzał na nią karcącym wzrokiem, chłopczyk dalej przestępował z nogi na nogę.

Dlaczego jest pan ateistą – w jego pytaniu nie było cienia agresji, raczej autentyczna ciekawość.

Odpowiedziałem, że sam się nad tym zastanawiam, że w czasach komunistycznych to było trochę wstydliwe, bo wśród ateistów są ludzie, z którymi człowiek wolałby nie mieć nic wspólnego, a wśród wierzących jest wielu takich, z którymi bardzo dużo mnie łączy. Jest jednak kilka ważnych powodów. Po pierwsze, nie mam dowodów na istnienie istot nadprzyrodzonych, po drugie musiałbym szukać najmniej paskudnej religii. Nie chciałbym wyznawać religii Azteków i wierzyć, że mój bóg oczekuje ludzkiej krwi, nie chciałbym być muzułmaninem i wierzyć, że mój bóg nagrodzi mnie 72 dziewicami za zabijanie niewiernych, nie chciałbym być chrześcijaninem i wierzyć w życie pozagrobowe. Mam 84 lata, niedługo umrę i bardzo by mnie męczyła perspektywa wieczności w jednej celi z Rydzykiem.

Kobieta żachnęła się.

– My nie jesteśmy od Rydzyka, my sobie inaczej tę wieczność wyobrażamy.

– Każda wieczna świadomość byłaby koszmarem, kres naszej świadomości jest piękną obietnicą, a tego życia, które mamy, nie warto marnować na puste gadanie.

– Dlaczego marnować – zapytała.

– Nie wiem jak to pani wyjaśnić. Pani mąż powiedział, że jesteśmy Homo sapiens, ale jesteśmy również Homo faber. Wpada Homo faber do kawiarni i mówi do Homo sapiens: przestań myśleć o niebieskich migdałach i zrób wreszcie coś pożytecznego dla innych.

– Pan zawsze żartuje – zapytała.

– Tak często jak to możliwe. Widzi pani, uśmiech i żart są jak ogon psa, pozwalają powiedzieć innym, że nie mamy wobec nich złych zamiarów, a życzliwość pozwala nam przetrwać w tym strasznym świecie. Serce nie sadysta, kiedyś przestanie bić, ale mam nadzieję, że uda mi się żartować do samego końca.

Przeprosiłem, że muszę już wracać do przerwanej pracy, wyjaśniając, że czytam właśnie artykuł o tym, kiedy straciliśmy ogony.

– Kiedy – zapytał chłopiec.

– Zanim zostaliśmy ludźmi, mniej więcej 25 milionów lat temu i teraz próbujemy zrozumieć jak do tego doszło.

– To dawno – powiedział chłopiec, a ja machnąłem im ręką na pożegnanie.

Wracając do biurka zastanawiałem się, czy przeczytaliby opowieść o moim ateizmie, czy odrzuciliby ją tak, jak ja lekceważąco odrzuciłem ich ulotkę.

Andrzej Koraszewski – Publicysta i pisarz ekonomiczno-społeczny.

Ur. 26 marca 1940 w Szymbarku, były dziennikarz BBC, wiceszef polskiej sekcji BBC, i publicysta paryskiej „Kultury”. Więcej w Wikipedii. Facebook

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com