Weganizm w Izraelu jest uważany za rasistowski wobec Palestyńczyków. Oczywiście.

Weganizm w Izraelu jest uważany za rasistowski wobec Palestyńczyków. Oczywiście.

Elder of Ziyon Tłumaczenie: Małgorzata Koraszewska

Na początku tego roku czasopismo „Settler Colonial Studies” opublikowało następujący artykuł:

Wegański nacjonalizm?: izraelski ruch na rzecz praw zwierząt w czasach walki z terroryzmem

Hiroshi Yasui

STRESZCZENIE

W ostatnich latach w Izraelu coraz większe znaczenie zyskuje ruch na rzecz praw i dobrostanu zwierząt (ruch na rzecz praw zwierząt), równolegle z praktyką etycznego weganizmu. Wraz z tym trendem w kilku badaniach rozważa się i analizuje kolonialne aspekty izraelskiego ruchu na rzecz praw zwierząt i jego znaczenie dla kwestii palestyńskiej z perspektywy Krytycznych Studiów nad Zwierzętami. Krytycznie analizując wcześniejsze badania na temat weganizmu i kolonializmu, poprzez analizę dyskursów politycznych czołowych aktywistów i osób publicznych w ramach nowo popularnego izraelskiego nurtu wegańskiego, a także wywiady z próbą izraelskich wegan, ten artykuł pokaże, w jaki sposób weganizm w Izraelu jest powiązany z narracją o izraelskiej wyższości narodowej. Takie dyskursy można śmiało nazwać „wegańskim nacjonalizmem”. Wegański nacjonalizm to ramy dyskursywne i regulacyjne, w których weganizm jest uważany za dowód moralnej wyższości narodu w kontekście kolonializmu osadniczego, pośrednio podkreślając barbarzyństwo i zacofanie „terrorystów”. Jednocześnie, jak wskazuje artykuł napisany przez Izraelskie Siły Obronne, w tym kontekście weganie prezentują mile widziany, pociągający wizerunek, który rezonuje, mimo że różni się od wizerunku silniejszego, solidniejszego i potężniejszego karnisty [wyznawca ideologii pozwalającej na jedzenie i wykorzystywanie zwierząt – przeciwieństwo weganina. przyp. tłum.] tradycyjnie faworyzowanego przez syjonistów.

Jak widzieliśmy w przypadku „pinkwashingu”, zasada oskarżenia polega na tym, że kiedy Izraelczycy robią coś, co jest zgodne z ulubionymi sprawami ruchu postępowego, należy to interpretować jako dowód na to, że Izraelczycy próbują ukryć swój z natury zły charakter.

Nie mam dostępu do artykułu, ale widzę przypisy. Żaden przypis, jaki widziałem, nie potwierdza jego tezy.

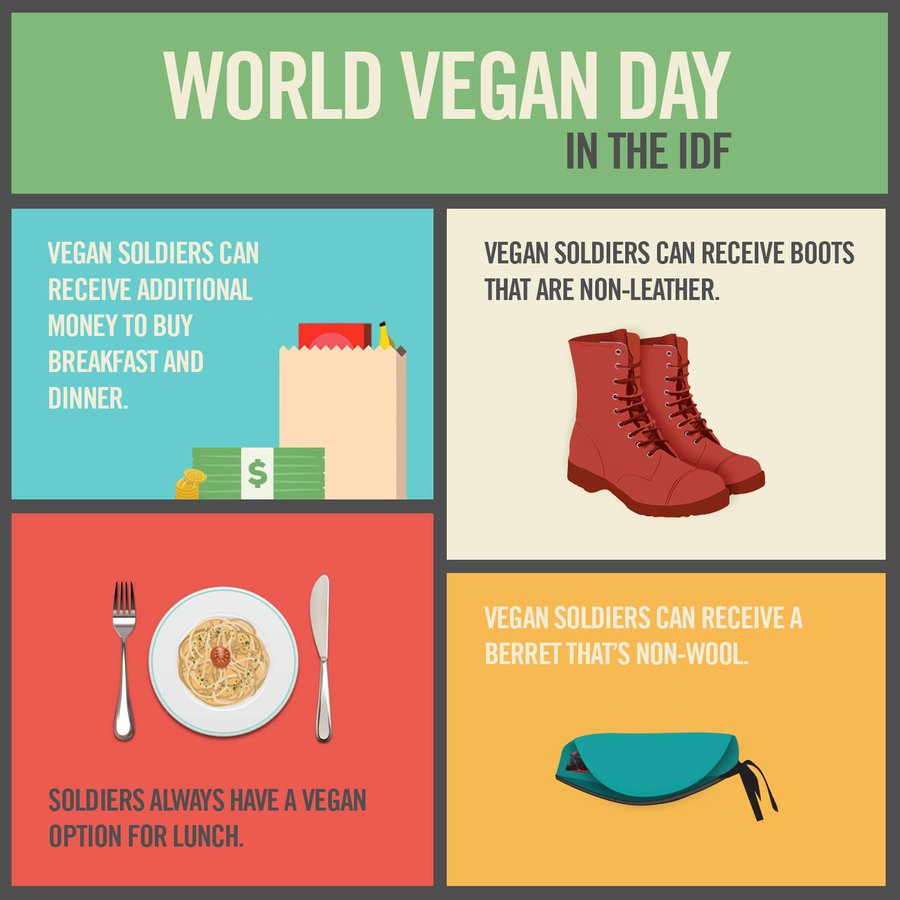

Na przykład widzę dwa odniesienia do strony internetowej IDF, gdzie rzekomo jesteśmy narażeni na narrację o żydowskiej supremacji moralnej, która poniża Palestyńczyków jako niemoralnych zjadaczy mięsa.

Jednym z nich był artykuł z 2017 roku w czasopiśmie IDF, który opisuje, w jaki sposób armia uwzględnia wegan, zarówno jeśli chodzi o wybór jedzenia, jak i odzieży, a drugim był bardziej obszerny artykuł o trudnościach bycia weganinem w IDF oraz o tym, jak armia pracuje nad tym, aby każdy czuł się dobrze. Omówiono nawet dylemat żołnierza, który zabija ludzi będąc weganinem:

Od czasu do czasu wegańscy wojownicy spotykają ludzi, którzy twierdzą, że sama ich rola jako wojownika jest niezgodna z ich aspiracjami do moralności, która wyraża się w wegańskim stylu życia. Major Friedman bardzo dobrze wie, jak sobie poradzić z tymi twierdzeniami. „Po prostu uważam, że to nieprawda. Zaciągnąłem się do wojska, żeby walczyć w obronie naszego kraju. W armii są bardzo jasne rozkazy, a nasza armia jest armią moralną. Jeśli w armii jest żołnierz, który robi coś, co jest zabronione, to zostaje ukarany – odpowiada. – Nie widzę związku między oszczędzaniem zwierząt a oszczędzaniem ludzi, którzy chcą zaszkodzić krajowi. Nasza armia nie jest armią przeznaczoną do zabijania, jest armią mającą na celu ochronę”.

Nie mogę znaleźć niczego w IDF, co choćby sugerowałoby, że uważa się ona za moralnie lepszą od jedzących mięso Palestyńczyków. Byłoby to absurdalne, skoro większość żołnierzy nadal je mięso. Ale jest uzasadniona duma, że oferuje żołnierzom wegańskim wybór jedzenia i odzieży.

Najbliższym przykładem wykorzystania przez IDF praw zwierząt do celów moralnych, jaki mogłem znaleźć, był ten tweet (który po prostu wskazuje, że Hamas krzywdzi zwierzęta):

Kiedy robi to PETA, jest to moralne; kiedy robi to IDF, jest to niemoralne.

Kiedy robi to PETA, jest to moralne; kiedy robi to IDF, jest to niemoralne.Mówiąc o PETA, na ich blogu opublikowano pochlebny artykuł na temat praw zwierząt w Izraelu (niecytowany w tym artykule: „Jeśli chodzi o uznawanie naturalnych praw zwierząt, Izrael wyprzedza wiele innych krajów. Izrael od dawna zakazuje sprzedaży produktów do pielęgnacji osobistej i gospodarstwa domowego, które są testowane na zwierzętach. Był to pierwszy kraj, który wprowadził zakaz używania wozów i powozów zaprzężonych w konie i osły do celów zawodowych”.

Inny artykuł, do którego autor omawianej pracy daje odnośnik, a który obala jego próby demonizowania Izraela, pochodzi z Vegan Review:

Okrzyknięta „najbardziej wściekłą weganką Izraela”, Tal Gilboa jest aktywistką, który robi różnicę.

W 2019 r., po dziesięciu latach działalności na rzecz praw zwierząt, została mianowana przez premiera Izraela jego doradczynią ds. dobrostanu zwierząt. Niektórzy postrzegali to jako manewr polityczny na rzecz Benjamina Netanjahu, ale dla Gilboa był to po prostu „historyczny dzień dla zwierząt”.

„W walce o zwierzęta nie ma lewicy ani prawicy – wyjaśniła. – Jeśli poprawia to dobrostan zwierząt i łagodzi ich cierpienie, jest to słuszna decyzja”.

Głos Gilboa nieco łagodnieje, gdy mówi o klanie Netanjahu. „To, co administracja Netanjahu zrobiła dla zwierząt, jest wzorowe – mówi. – To powinno mieć miejsce na całym świecie – działać w ramach panującego rządu, zamiast czekać, aż uformują się małe nisze zajmujące się prawami zwierząt; te nisze nie dają rezultatów”.

W ciągu czterech miesięcy na swoim nowym stanowisku Gilboa osiągnęła więcej, niż kiedykolwiek marzyła. Do jej zwycięstw dla zwierząt należy zakaz handlu futrami i polowania na niektóre gatunki ptaków. Pomogła także w opracowaniu ustawy Kaya (nazwanej na cześć psa Netanjahu), zgodnie z którą zaszczepione psy podejrzane o ugryzienie kogoś mogą zostać poddane kwarantannie w domu, zamiast być odbierane siłą właścicielom.

Żadne z tych źródeł nawet w najmniejszym stopniu nie pasuje do tego dziwacznego streszczenia. Aby obwiniać całe izraelskie społeczeństwo, autor musi uciekać się do cytowania zastępcy burmistrza Jerozolimy, który nazwał terrorystów „zwierzętami”, rzucając tym słowem jak obelgą.

Także jeśli przeszukasz ogólnie hasło dotyczące weganizmu w Izraelu, znajdziesz wiele artykułów, ale żaden z tych, które znalazłem, nie wspomina w jakikolwiek sposób o Palestyńczykach.

Chociaż nie ma dowodów na to, że Izraelczycy wykorzystują weganizm, aby ustawiać się jako osoby moralnie czyste w przeciwieństwie do Palestyńczyków, ogólnie rzecz biorąc, weganie są dobrze znani z tego, że są nieznośnie zadowoleni z własnej wyższości moralnej nad wszystkimi innymi.

Trudno oprzeć się wrażeniu, że autor tego artykułu przenosi swój własny pogląd, że jest moralnie lepszy od osób jedzących mięso, Izraelczyków i Palestyńczyków. To nonsens, ale tylko to wyjaśnia tę pracę, której własne przypisy nie potwierdzają tezy badacza.

Publikacja w „Settler Colonial Studies” sprawia, że cała dziedzina badań nad kolonializmem osadników wygląda jak kiepski dowcip.

Link do oryginału: https://elderofziyon.blogspot.com/2024/06/veganism-in-israel-is-considered-racist.html

Elder of Ziyon, 23 czerwca 2024

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com