W ostatnich latach Irańczycy wszczęli niezliczone powstania, każde pełne nadziei i odwagi, tylko po to, by spotkać się z brutalnymi represjami ze strony reżimu i głównie obojętnością ze strony zagranicy. Przy każdej fali protestów siły bezpieczeństwa zabiły tysiące demonstrantów, a wielu innych uwięziły i torturowały. Już dawno nadszedł czas, aby państwa zachodnie zajęły ostre stanowisko. Na zdjęciu: irańscy policjanci ścigają antyreżimowych protestujących i biją ich pałkami w Teheranie, 19 września 2022 r. (Zdjęcie: AFP via Getty Images)

W ostatnich latach Irańczycy wszczęli niezliczone powstania, każde pełne nadziei i odwagi, tylko po to, by spotkać się z brutalnymi represjami ze strony reżimu i głównie obojętnością ze strony zagranicy. Przy każdej fali protestów siły bezpieczeństwa zabiły tysiące demonstrantów, a wielu innych uwięziły i torturowały. Już dawno nadszedł czas, aby państwa zachodnie zajęły ostre stanowisko. Na zdjęciu: irańscy policjanci ścigają antyreżimowych protestujących i biją ich pałkami w Teheranie, 19 września 2022 r. (Zdjęcie: AFP via Getty Images)

Wesprzyjmy ludzi w Iranie, którzy pragną zmian i wolności

Wesprzyjmy ludzi w Iranie, którzy pragną zmian i wolności

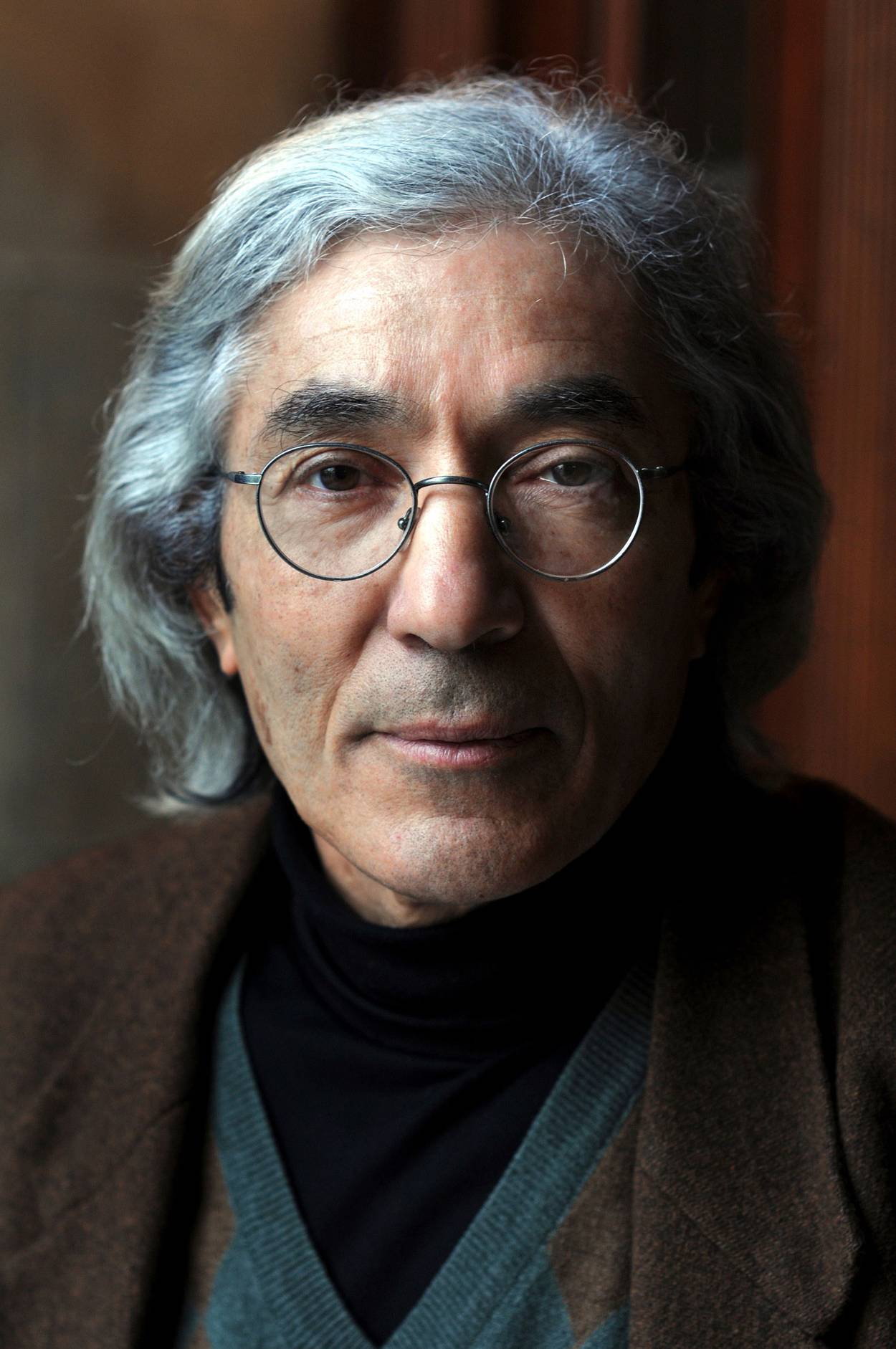

Majid Rafizadeh

Tłumaczenie: Małgorzata Koraszewska

Przez dziesięciolecia odważni mieszkańcy Iranu raz po raz powstawali, domagając się wolności od ucisku i autorytarnych rządów.

W ostatnich latach Irańczycy wszczęli niezliczone powstania, każde pełne nadziei i odwagi, tylko po to, by spotkać się z brutalnymi represjami ze strony reżimu i niemal całkowitą obojętnością z zagranicy. Przy każdej fali protestów siły bezpieczeństwa reżimu zabijały tysiące demonstrantów, a wielu innych uwięziły i torturowały. Ruchy te pokazały siłę determinacji narodu irańskiego, ale pomimo ich krzyków o wolność, poparcie ze strony Zachodu — zazwyczaj jedynie słowa o ideałach demokracji — pozostało rozczarowująco wyciszone.

W oczach wielu Irańczyków milczenie ze strony demokratycznych państw, które rzekomo bronią praw człowieka, stoi w sprzeczności z ich zasadami i wielokrotnie sprawiało, że irańscy protestujący czuli się porzuceni w swojej walce.

Podczas ogólnokrajowych protestów w 2022 r., wywołanych przez prawo o hidżabach, wielu Irańczyków, zwłaszcza młodych kobiet, wyszło na ulice, aby zaprotestować przeciwko obowiązkowemu zasłanianiu głowy i innym represyjnym prawom. Ruch ten stanowił nie tylko sprzeciw wobec surowych islamskich kodeksów ubioru, ale także szersze odrzucenie autorytarnych rządów reżimu. Nawet gdy doszło do represji — reżim aresztował, bił, a nawet mordował protestujących — reakcja Zachodu pozostała w dużej mierze bierna i bezwładna, zamiast oferować zdecydowane wsparcie. Irańczycy ryzykujący życie na ulicach, ośmieleni nadzieją na międzynarodową solidarność, pozostali bez jakiegokolwiek wsparcia, którego wielu oczekiwało od krajów deklarujących wspieranie wolności i praw człowieka.

W 2009 r. w Iranie wybuchł Ruch Zielonych po budzących wątpliwości wyborach prezydenckich. Miliony Irańczyków wyległo na ulice, skandując hasła, machając transparentami i potępiając to, co wielu uznało za sfałszowany wynik wyborów. Protestujący domagali się uznania ze strony światowych liderów, w szczególności administracji Obamy w Stanach Zjednoczonych i europejskich liderów, w nadziei, że te demokratyczne kraje poprą ich apel o uczciwy proces wyborczy i zakończenie ucisku.

Protestujący skandowali: “Obama, jesteś z nami czy mułłami?” — jako bezpośredni apel do ówczesnego prezydenta USA Baracka Obamy o zajęcie stanowiska. Jednak ku rozczarowaniu wielu Irańczyków, zachodni przywódcy właściwie milczeli, decydując się nie interweniować ani nie oferując żadnego realnego wsparcia. Obama później przyznał, że milczenie jego administracji w tym krytycznym okresie było “błędem”, ale nawet wtedy wspomniał tylko o nieskutecznym, słownym wsparciu:

“Z perspektywy czasu uważam, że to był błąd. Za każdym razem, gdy widzimy błysk, iskierkę nadziei, ludzi tęskniących za wolnością, myślę, że musimy na to zwrócić uwagę. Musimy rzucić na to światło reflektorów. Musimy wyrazić solidarność w tej sprawie”.

Podczas gdy większość demokratycznych krajów wahała się, czy otwarcie przyłączyć się do irańskich ruchów prodemokratycznych, jeden kraj wyróżnił się jako niezachwiany sojusznik narodu irańskiego: Izrael. Mimo długotrwałej wrogości między Izraelem a reżimem Iranu, izraelscy przywódcy odważnie poparli prawo narodu irańskiego do wolności i samostanowienia. Premier Izraela Benjamin Netanjahu, nazywany “Churchillem Bliskiego Wschodu”, nie tylko odniósł się do irańskich gróźb nuklearnych — podczas gdy USA próbowały podważyć działania Izraela przez ujawnienie jego planów – ale zwrócił się bezpośrednio do Irańczyków za pośrednictwem mediów społecznościowych, mówiąc im, by nie tracili nadziei. “Jest jedna rzecz, której reżim Chameneiego boi się bardziej niż Izraela — oświadczył Netanjahu w poście na X. – Boi się was — narodu Iranu”. Dodał:

“Poświęcają tyle czasu i pieniędzy, próbując zniszczyć wasze nadzieje i ograniczyć wasze marzenia. Nie pozwólcie, by wasze marzenia umarły. Nie traćcie nadziei i wiedzcie, że Izrael i inni w wolnym świecie stoją z wami”.

Netanjahu poszedł jeszcze dalej, wyobrażając sobie przyszłość, w której wolny Iran mógłby wykorzystać swój pełny potencjał. Powiedział, że pod rządami innego rządu dzieci Iranu mogłyby uzyskać dostęp do edukacji na światowym poziomie, ludzie mogliby korzystać z zaawansowanej opieki zdrowotnej, a infrastruktura kraju mogłaby zostać odbudowana, aby zapewnić czystą wodę i niezbędne usługi. Netanjahu obiecał nawet pomoc Izraela w odbudowie wodnej infrastruktury Iranu, przytaczając jako przykład najnowocześniejszą technologię odsalania wody w Izraelu.

“Od czasu, gdy ostatnio mówiłem do was – kontynuował Netanjahu – reżim Chameneiego wystrzelił setki pocisków balistycznych w mój kraj, Izrael. Ten atak kosztował 2,3 miliarda dolarów”. Rzeczywiście, te miliardy, zamiast zostać wydane na daremne ataki, mogłyby zostać skierowane na potrzeby narodu irańskiego, wzmocnienie ich systemów edukacji i opieki zdrowotnej lub poprawę transportu. Ujmując problem w kategoriach marnotrawstwa zasobów, Netanjahu podkreślił lekkomyślne wydatki reżimu kosztem obywateli, podkreślając, że naród irański zasługuje na coś lepszego.

Takie przesłania najwyraźniej znalazły oddźwięk wśród wielu Irańczyków, którzy w innym kraju widzą promyk nadziei i znak, że nie są zupełnie osamotnieni w walce z represjami reżimu:

“8 października, dzień po atakach [Hamasu w 2023 r.]… kilku prorządowych działaczy próbowało podnieść flagę palestyńską na trybunach [stadionu piłkarskiego]. Reakcja, z jaką się spotkali, była natychmiastowa. Tysiące kibiców zaczęło krzyczeć hasło sformułowane w charakterystycznym stylu kibiców piłkarskich na całym świecie: “Wsadźcie sobie flagę palestyńską w dupę”.

Postawa Izraela stoi w oślepiającym kontraście do postawy wielu krajów zachodnich, szczególnie tych w Europie. Podczas gdy Izrael, naród obecnie atakowany na wielu frontach, stanowczo stanął po stronie narodu irańskiego, wiele krajów europejskich nadal stawia więzi gospodarcze z Teheranem ponad prawa człowieka.

Rządy europejskie, zamiast ryzykować konfrontację z reżimem Iranu, wolą utrzymywać z nim stosunki biznesowe i unikać zajmowania stanowiska, które mogłoby zdenerwować mułłów. Kraje te są współwinne cierpieniom narodu irańskiego. Niezmącona cisza ośmiela reżim, zamiast pociągać go do odpowiedzialności.

Po prawie czterdziestu latach utrzymywania stosunków dyplomatycznych z Islamską Republiką Iranu już dawno minął czas zajęcia zdecydowanego stanowiska przez państwa zachodnie. Jeśli te kraje naprawdę wierzą w zasady “demokracji” i “wolności”, które tak często głoszą, wyglądałyby to o wiele bardziej wiarygodnie, gdyby zademonstrowały to deklarowane zaangażowanie, szczerze wspierając Irańczyków tęskniących za wolnością.

Oznaczałoby to zerwanie stosunków dyplomatycznych z Iranem, nałożenie i egzekwowanie poważnych sankcji podstawowych i wtórnych wobec reżimu, rozważenie opcji militarnych oraz pełne wsparcie Izraela, a mamy nadzieję także nowej administracji USA, w dążeniu do trwałego położenia kresu irańskiemu programowi nuklearnemu, a także jego brutalnemu, ekspansjonistycznemu reżimowi.

Dopiero wtedy działania tych państw będą zgodne z ich podejrzaną retoryką na temat “praw człowieka” i pokażą, że są one gotowe udzielić realnego wsparcia tym, którzy ryzykują życie, by wprowadzić zmiany w jednym z najbardziej represyjnych państw na świecie.

Majid Rafizadeh: Amerykański politolog irańskiego pochodzenia. Wykładowca na Harvard University, Przewodniczący International American Council. Członek zarządu Harvard International Review.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com