Bibi’s Typist

Bibi’s Typist

OPHIR FALK

Transcribing the Israeli leader’s autobiography helped me see Netanyahu in a new way.

.

A ‘young man in a hurry’: Netanyahu in 1985FRANCK MICELOTTA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

A ‘young man in a hurry’: Netanyahu in 1985FRANCK MICELOTTA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Do you know an English typist?” Netanyahu’s office asked me shortly after he lost the 2021 elections.

“I’ll do it,” was my immediate reply. I figured he was surely looking for someone to type his upcoming book.

While waiting for Netanyahu to get back to me, I asked my eldest son, “Don’t you think I’m maybe a bit overqualified? Besides, decoding Netanyahu’s shorthand and being on call for him 24/7 was something I did back in 2006, when I worked for him on a previous book.”

“Dad,” my 18-year-old said, “it’s like taking rebounds for Michael Jordan. You gotta do it.” My son, a professional basketball player at the time, was right and I knew it.

The following evening, Netanyahu handed me 10,000 words that he had handwritten earlier that morning and asked me to give it a go. I did my best to quickly return a typed version.

Basketball fans out there can appreciate that, before the ball hit the floor, I had to return the typed text. He seemed satisfied and handed me an additional 10,000 words. At first, things were technical but over time I asked questions and occasionally commented on some of the shots. He welcomed that. A few shots were challenged and altered but Netanyahu’s eyes were firmly focused on the rim.

It was a frenzied period of collaboration during which Netanyahu was to write, edit, and rewrite some 230,000 words, while back-seat driving down Israel’s rural roads and even while sitting in court hearings. In parallel, we were going through new COVID outbreaks and political battles to bring down the Bennett-Lapid government. A little over nine months from its commencement, a book was born. A book that tells the story of Netanyahu, his family, and his people.

The courtside seat gave me an opportunity to see how Netanyahu addresses big issues like the threat of a nuclear Iran, free-market reforms, and peace in the Middle East. I also saw how he appreciates the small things, like a walk in the park or on the beach, freshly squeezed lemonade, an evenly sliced Snickers chocolate bar and yes—an occasional cigar.

I also saw a more seasoned leader, since the last time I worked with him over a decade ago. Beyond being a gifted speaker and writer, he became a much better listener, and after adapting to the TikTok and Twitter era, he even developed a sense of humor.

The process of assembling the book was straightforward. Netanyahu would jot down a chapter title, a timeline, and would start writing. He would send me handwritten text, I would type it into Word, including questions and comments when applicable and send it back to him via WhatsApp. It would also be printed out for him in double-spaced, size 14 font. He would edit the chapter and address the comments, on the hard copy, when relevant. Once he felt comfortable with the text, I would send it to his brother Iddo and two of his trusted friends, Ron and Gary, for feedback while Sharon did the fact-checking. Once that was done, we’d send it to Max at Simon & Schuster.

On one of his drives to Caesarea from a late-night meeting in Jerusalem he stopped by my home for a “short session” to “tighten up the text.” While waiting for the laptop to boot up, he looked over the living room bookshelves and seemed pleased to see one of his books between Yoni’s Letters and Jabotinsky’s biography. That night, from midnight until the sun peaked over the nearby Samarian hilltops, he aligned paragraphs and cut commas, indulging only on leftover popcorn from my 8-year-old’s birthday party, with black coffee to wash it down.

As Netanyahu dove deeper and longer into the text his inner circle expressed growing concern that he “preferred being a writer than a prime minister” and was investing the lion’s share of his time on the book rather than getting reelected. I have no doubt that he enjoys the writing process more than the political process. As he once wrote, “Writing consumed me. On a good day, writing forces you to distill ideas, to order them logically and to breathe life into them with unexpected language. For me there is no more satisfying intellectual exercise.”

But he knew when it was time to pivot to the campaign and then “left it all on the field.”

Of all his idiosyncrasies, his ability to focus and prioritize was most impressive. He could focus on fine-tuning a speech with Yonatan and Hagai while simultaneously listening to the news on channels 11, 12, 13, and 14. When someone said something important on one of the channels, he would switch from the speech to the screen and back to the speech without losing a beat.

Netanyahu seldom raises his voice, but you can clearly see when he is disappointed in you. I got that strong impression when he thought I had not properly incorporated into the text the iconic “eye to eye” exchange he had with Rabbi Leibovitch in 1988 before returning to Israel from his United Nations mission.

“You know it takes a lot of time and thought to put the right words on paper,” he told me.

The problem was he had not given me the text.

“You are probably right seven to nine times out of 10 but this time you’re wrong. You didn’t give me the text,” I replied.

Once the script was found in his folder, he half jokily retorted, “I might have been wrong this time, but the odds are closer to 99 out of 100.”

Fixing footnotes and picking photos for the book were the most Sisyphean and sensitive parts of the project. My wife wisely told me not to touch the latter. Netanyahu is one of the world’s most photographed people and the publisher’s willingness to include 106 photos, while generous, didn’t make the selection process much easier. Michal and Topaz carried most of that burden.

Netanyahu seemed to like the ones of him and his son Avner walking on the beach, the “get well soon” painting his son Yair drew for an ailing King Hussein, the one with his daughter Noa at his grandson’s bris and the ones with Yoni most. He also liked the ones with his wife, Sara, strolling on the Golan Heights, and with Ronald Reagan at the White House’s red room.

Netanyahu wrote his most moving chapter in a Netanya hotel room in the middle of the night after celebrating Yair’s 30th birthday. The chapter was initially titled “Yoni,” and it was the only one I had trouble transcribing. Like Netanyahu, I was also raised by a brilliant professor father and similarly smart and sensitive mother. They also lost a beloved son in his youth. Netanyahu’s candid portrayal of the endless drive from Boston to Ithaca and how his parents coped with inconceivable grief hit home.

The book goes through the major life events of a “young man in a hurry,” who became the youngest prime minister of Israel in 1996, to the intersections he crossed on his way to becoming the longest serving prime minister in 2021.

The most interesting part for me was watching him make decisions.

Seeing decisions made that can immediately impact your nation is drastically different from reading about them in the news or studying about them in university. Netanyahu’s ability to listen, ask the right people the right questions, “trust but verify” the answers and weigh the options have helped him realize opportunities, avoid unnecessary risks, and most importantly, save lives.

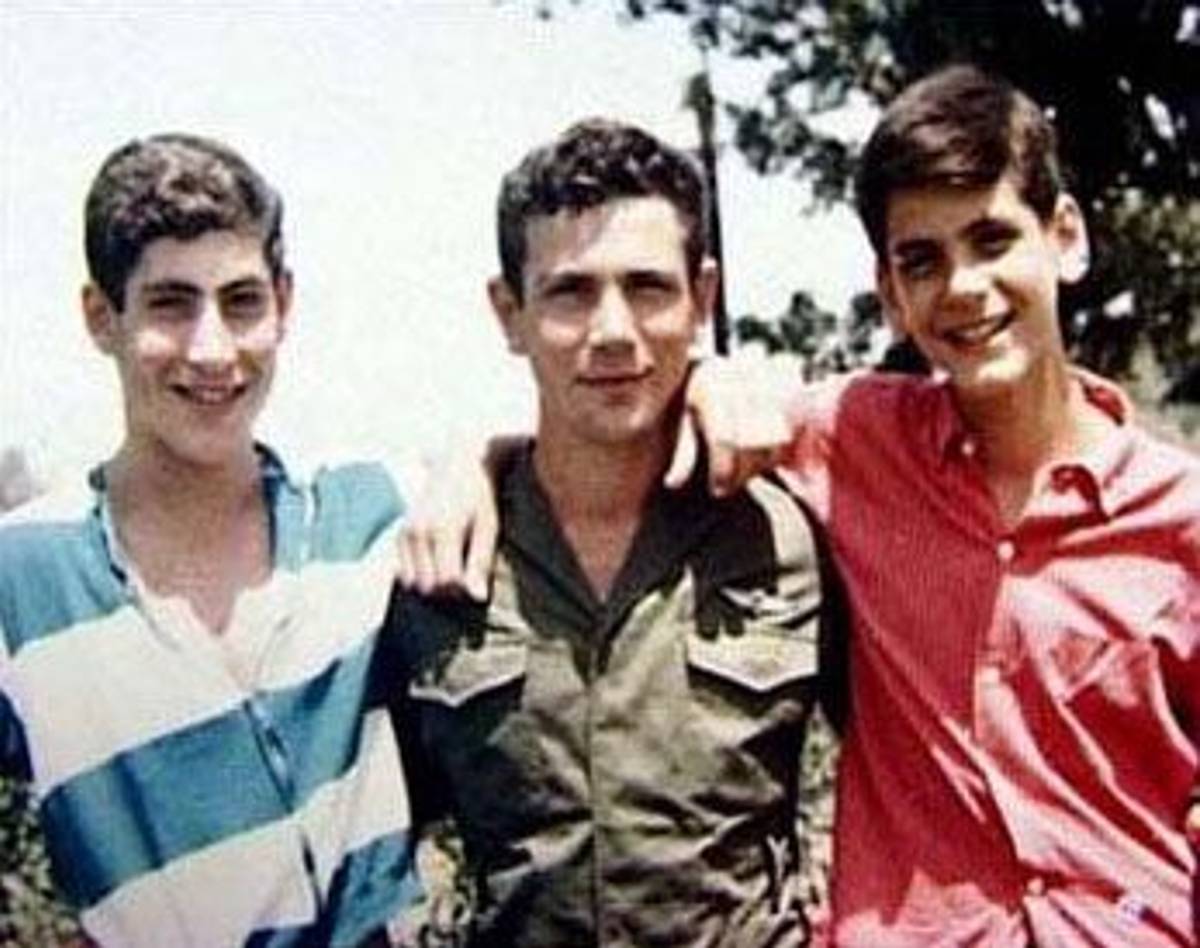

Benjamin, Yoni, and Iddo Netanyahu in an undated family photoYONI NETANYAHU MEMORIAL WEBSITE

Benjamin, Yoni, and Iddo Netanyahu in an undated family photoYONI NETANYAHU MEMORIAL WEBSITE

Scores of crucial decisions are described in the book, including the 1996 declaration before a joint session in Congress to forgo civilian foreign aid, the decision to overhaul Israel’s semi-socialist economy into a free market one in 2003, the 2005 “disengagement” from Gaza, the mistaken “Shalit swap” in 2011, and the decision to present before Congress the case against a dangerous Iranian nuclear deal sponsored by Barack Obama.

These were controversial decisions that entailed taking significant political risks for what Netanyahu viewed as vital national interests. He put Israel’s interests above his political ones. If those decisions would turn sour, he would lose at the ballot box. That was something he was willing to do, and in fact did in 2006, when his economic reforms had an adverse effect on many of his constituents. In the long run those reforms helped transform Israel into a global power.

One decision was different.

It entailed significant personal risk.

Shortly after his corruption trial commenced, Netanyahu was offered a plea bargain. The case would be closed, and the 72-year-old leader would be spared lengthy and costly litigation. But he would also need to admit to certain charges and leave political life for years.

He could’ve taken the deal. He would be a free man who could easily make millions, and as the longest serving Israeli prime minister—one who forged four historic peace agreements and brought his people unprecedented power and prosperity—his legacy was secure. He had little more to prove.

The deal, however, was unacceptable to him. He heard out the lawyers, a friend and adviser or two, but first and foremost he listened to his family.

The plea bargain was taken off the table and Netanyahu went all in.

As the state witnesses came to the stand the case began to crumble. Despite hundreds of millions of dollars invested into Netanyahu’s investigation and prosecution, most of the public stopped buying into the allegations and the slanderous stories leaked to nightly newscasts.

Netanyahu is no Mother Teressa, but he is not corrupt.

The book came out in mid-October 2022. It was read by thousands of Israelis and is believed by political pundits to have had an “October effect” on the elections.

On Nov. 1, 2022, Israelis went to the polls and gave Netanyahu a vote of confidence and a landslide victory. Two months later, Netanyahu was sworn in as prime minister and formed a government for the sixth time.

Ophir Falk is a lawyer and an author, most recently, of Targeted Killing, Law and Counterterrorism Effectiveness. He is the CEO of Acumen Risk Ltd. and co-produced The Trial, a movie that documented the early stages of Netanyahu’s trial.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com