The Forgotten Pioneer of Movie Music

The Forgotten Pioneer of Movie Music

KAREN IRIS TUCKER

CHLOE NICLAS

CHLOE NICLAS

.

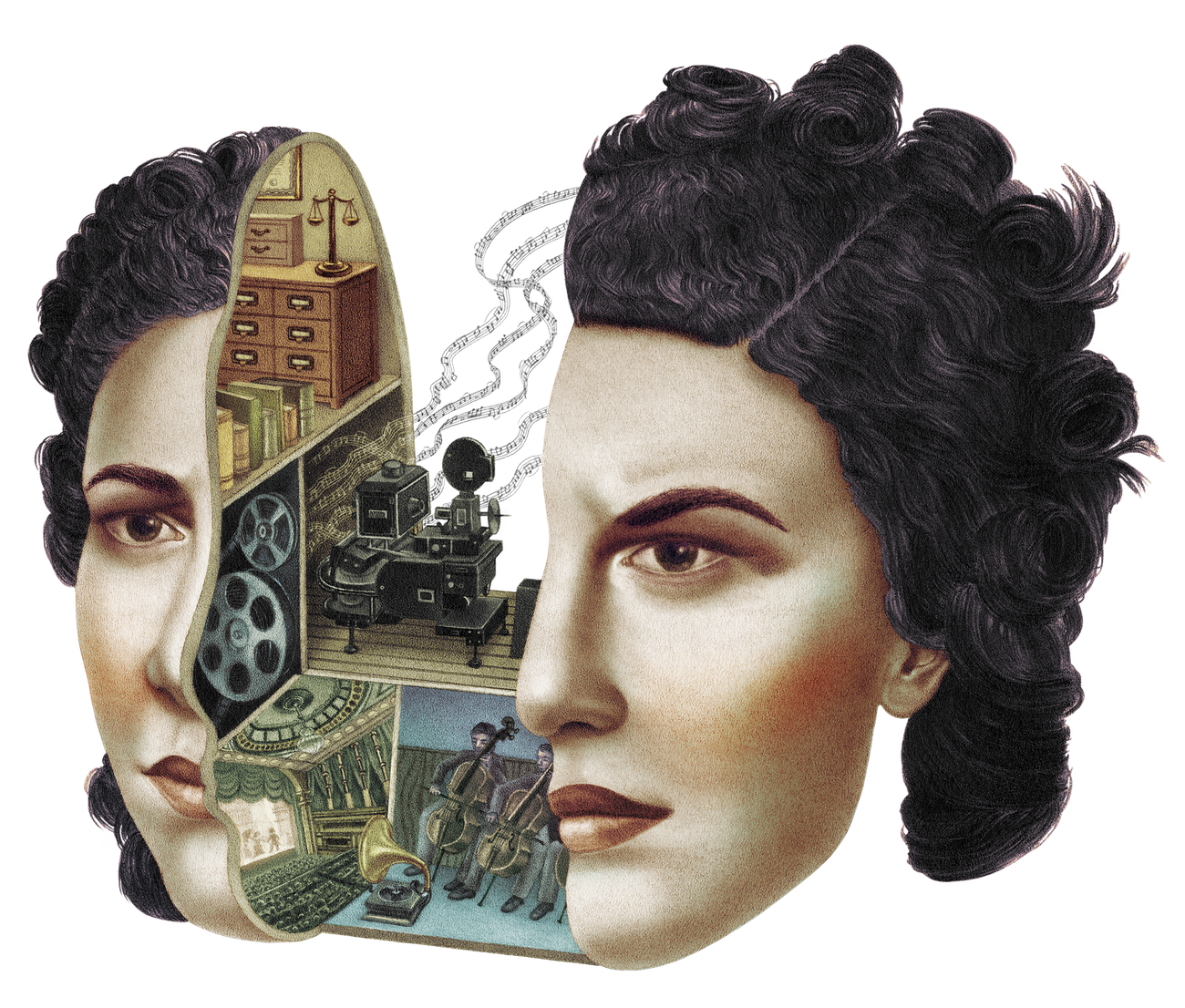

The daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, Ottalie Mark left her mark on the film industry—and the music industry—a century ago

It was the early 1920s and the dawn of the transition from the silent film era to the invention of synchronized sound and “the talkies.” Ottalie Mark—a young secretary for the lavish Capitol Theatre movie palace in Manhattan—probably had no idea she would come to be an unlikely, if crucial, centerpiece of the business world at the intersection of music, film, and the law.

Yet there were clues in Mark’s origin story that indicate that she was not much of a sideline-sitter or a fan of letting fate define her destiny. For starters, she was born in 1896 but fibbed for posterity, according to her great-grandnephew Richard Grimes, now 80: “She was a headstrong woman to the point that she had her grave marker inscribed before she died, making herself 13 years younger.”

She was the daughter of first-generation Russian Jewish immigrants—David, who worked in the garment industry, and his wife, Rose—and sibling to four sisters and four brothers. During Mark’s early years they all lived together at 76 Chrystie St. on the Lower East Side. Mark attended NY Prep, got an undergraduate degree in pre-law from NYU, and enrolled as a Yeomen Second Class in the Navy during WWI, serving as a clerical worker. This was all before she began pursuing her professional career, said Keith D’Arcy, senior vice president, sync & creative services at Warner Chappell Music.

D’Arcy, 54, is the researcher and compiler of an extensive Wikipedia page devoted to Mark’s life—the only comprehensive known document available about her. He embarked on that project after finding a few intriguing paragraphs about Mark in the 1939 book The Story of the House of Witmark: From Ragtime to Swingtime, by journalist Isaac Goldberg and Isidore Witmark, a prominent music publisher and composer. D’Arcy stumbled upon the book in 2019 while researching the origins of Warner Bros. when he arrived at his job at Chappell, a music-publishing subsidiary of the company.

He found that Mark’s life was punctuated by monumental moments in cinema and music, beginning with her first stop in the business world: Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel’s Capitol Theatre. The theater would prove an exciting and inventive vortex of film and radio at the time, and a key facilitator of the film industry’s use of broadcasting for the promotion of motion pictures.

“The Capitol Theatre Orchestra was Roxy conducting live on radio,” said Jeannie Pool, a composer, musicologist, and co-author with H. Stephen Wright of A Research Guide for Film and Television Music in the United States. “Silent film music was broadcast on radio, including the overtures to major films, as a way of promoting the films. That is why the film studios first started live radio stations.”

During this time of media cross-pollination and innovation, Mark had the fortune to work with two pivotal characters at the Capitol Theatre. She was secretary to its head of publicity, Martha Wilchinski, one of the best-known publicists in the business at the time. Mark was also an assistant to Ernö Rapée, the theater’s famed music director. Under his tutelage, Mark worked with the orchestra as a cueing assistant, rehearsing the musicians on which cues to play during each scene in the silent film theater.

As D’Arcy found, it wasn’t long before Mark moved on, taking with her the experience she had amassed in live orchestra, radio, and film. She was hired in the fall of 1925 by Warner Theatre as an assistant to its music director, Herman Heller. The following year, Mark was promoted to director of programming at its radio station, Warner Bros. Pictures Incorporated, and began coordinating interviews and live-music performances.

Like other significant touch points in Mark’s career, her timing was critical. Movie mogul Sam Warner, co-head of Warner Bros., was fascinated with emerging technology. He asked Heller to experiment with Vitaphone, an invention that would ultimately be the industry’s first commercially successful attempt to combine moving images with sound.

Mark was perfectly poised for the moment. “She naturally assisted Heller in the process, with all her experience with live orchestral music,” D’Arcy said. Mark was also a composer and lyricist in her own right, having studied music with conductor Sunia Samuels and violinist Michael Sciapiro.

Of Warner’s seminal interest in Vitaphone, D’Arcy said, “Warner Bros. quickly realized that a great product for this new invention would be movie musicals—taking Broadway and Vaudeville and putting it onto the screen.” He added that the company could then, incidentally, get rid of all the expensive orchestral musicians on its payroll and prerecord the soundtracks to its films.

The company ultimately used Vitaphone in its film Don Juan, which was retrofitted with a symphonic musical score and sound effects but did not have spoken dialogue. Starring John Barrymore as the famed playboy, it was the first feature-length film to use the Vitaphone technology. The film debuted on Aug. 5, 1926, at a gala Warner Bros. hosted at its theater in New York. Although the industry would, in a few short years, replace Vitaphone with better technology, it was a landmark event that revolutionized motion pictures.

It was at this point that our heroine sensed the need to pivot. “Ottalie realized that her job working with the live orchestra was about to go out the window because they were going to fire all the musicians,” D’Arcy said. An opportunity arose when Warner Theatre was sued for lacking a license to the copyrighted compositions in Don Juan, specifically for synchronization rights. Heller wanted to ward off future such infringement cases, so he charged Mark with building a database of popular songs Warner Bros. could use, and also tasked her with clearing the rights to those songs from Tin Pan Alley publishers.

And thus it came to be that Ottalie Mark of 76 Chrystie St. became one of the first people in the United States—if not the first—to build a database for the purpose of synchronization licensing. She began the painstaking task of documenting songs’ authorship and rights-holder information using an index-card system she created by hand.

“Until Mark built the synchronization database for Warner Bros., there was no way to obtain accurate information on song ownership without contacting ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers] directly,” D’Arcy said. He theorizes that she likely simply walked around to meet with all the publishers, which were clustered on Broadway between 42nd and 52nd streets in Manhattan, and within easy walking distance of the theater.

In her pioneering role of handling music licensing, Mark may have paved a path for the music supervisors of today.

Despite being largely uncredited in the annals of sync licensing, Mark’s work does live on in the archives. Katherine Spring, associate professor, Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, was conducting research for her book Saying It With Songs: Popular Music & the Coming of Sound to Hollywood Cinema when she found evidence of Mark’s record-keeping.

“I was looking at these licenses and I just noticed that some of them were signed by Ottalie Mark,” she said.“I thought, ‘Well, that’s interesting—that sounds like a woman’s name.’ It stood out to me because of course, I had only seen men’s names on all of these documents, except for the names of actresses who were appearing in the films I was studying.”

She added of Mark’s legacy: “It was a period of the studios trying to figure out how to make this new technology economically profitable while reducing risks. Mark’s role in that system was highly significant given that copyright infringement was such an important part of the transition to sound.”

It is possible that in her pioneering role of handling music licensing, Mark may have paved a path for the music supervisors of today, suggests Daniel Goldmark, professor and director of the Center for Popular Media Studies at Case Western Reserve University. “The music supervisor position in the late ’80s, when soundtrack films started becoming really big—many of those jobs were held by women. I’m wondering if there’s a throughline from what Mark was doing in the late ’20s to other women fulfilling this role 50 years later.”

Mark was so successful in her efforts at Warner Bros. that in 1929, Western Electric lured her away to become its supervisor of music rights. Working for the company’s subsidiary, Electrical Research Products Inc., Mark relocated to Hollywood to administer a five-year business arrangement called “The Mills Agreement.” Western Electric essentially struck a deal with publishers to pay them a flat fee in exchange for pre-clearance of their songs.

“So, all the songs that ASCAP controlled at the time could be pre-cleared under The Mills Agreement, and it was administered by Ottalie,” said D’Arcy. “So now, she’s a single woman living in Burbank, and becomes the sole music-rights clearance expert to the entire film industry.”

Mark’s daily work entailed interfacing with each studio to set up their filing systems, helping them collectively record the copyright history of hundreds of thousands of compositions. She did this until 1933, when The Mills Agreement had come to an end and Vitaphone had largely been replaced by more efficient technology. Mark then moved back home to New York and set up her own music rights consultancy, which she ran for several years.

It was then that the industry, by now fully enamored with Mark, came calling again for her expertise. The performing rights organization Broadcast Music Incorporated hired Mark as its first head of copyright research. She handled infringement claims against BMI’s songwriters and built the group’s copyright database.

D’Arcy says it may have been during this time that Mark met the love of her life, Philip F. Barbanell, a staff attorney who had worked at both Paramount and RKO Pictures. Records indicate the couple married in 1943, when Mark was 47 and Barbanell had returned from military service after serving as a lieutenant in the air force during WWII. A year after they married, Mark decided to build on the undergraduate degree she had earned in pre-law decades earlier. She enrolled at New York Law School and began studying for the bar exam.

By now, the trade papers were gossiping about her every move, with Variety proclaiming, “Ottalie Mark, head of BMI’s research department for the past seven years, handed in her resignation … She’ll concentrate on studies for admission to the bar.” Once Mark passed the exam, she established her own copyright research consulting company in the Paramount Theatre building, working with clients across the entertainment industry. Later, she and Barbanell shared office space and worked together in an entertainment law practice. Mark also continued as a composer and lyricist, publishing numerous songs until the 1970s.

Being both a composer and a copyright lawyer likely set Mark apart in her career, according to Pool, the co-author of A Research Guide for Film and Television Music: “She could actually read the music and know what it says, compare one piece with another, and decide whether it was infringement. So she had that unique skill set. A lot of people who knew the law and knew about copyright didn’t know how to do that.”

Beyond her legal work in private practice, we don’t know much more about Mark from the 1950s until her death in 1979 at 83. Family members do, however, offer a few glimpses of her more personally, giving the impression that like many of us, Mark was a mixed bag of attributes. Grimes, her great-grandnephew, said, “She was independent and not particularly liked in the family. I think she lived a mostly isolated life after she married Phil and was living in New York.”

Eileen Travis, Mark’s great-grandniece, recalls the pair visiting her home a number of times in Syosset, Long Island, when she was in grade school: “It was just the two of them. They traveled together and they came out to the Island to visit together. I imagine they were a pretty tight couple.” Travis, 76, a clinical social worker with the New York City Bar Association, remembers that Mark “was a big woman with a big personality. I do remember her being a little flamboyant. She was just full of energy and she spoke a lot. She was also very sophisticated in her dress.”

For all the professional affirmation Mark received in the industry during her time—if not in today’s history books—her personal life is something of a mystery. Even family members say they were largely unaware of her career success, and did not know much about her more generally. The totality of her life, therefore, remains largely incomplete to us.

Great-grandnephew Michael Mark, 74, has little recollection of his great-aunt aside from this: “She was a force. I remember that she once banged on my father and stepmother’s door for some photos she thought were hers and threatened to sue them.”

Grimes has a similar off-color memory from about 1949. “I vaguely recall seeing her walk into my grandmother’s apartment shortly after my grandfather—her oldest brother—died, and taking a marble statue out of the living room and walking out. We never saw her again.”

Karen Iris Tucker is a freelance journalist who writes primarily about health, genetics and cultural politics. Find her work at kareniristucker.com and follow her on Twitter at @kareniristucker.

Zawartość publikowanych artykułów i materiałów nie reprezentuje poglądów ani opinii Reunion’68,

ani też webmastera Blogu Reunion’68, chyba ze jest to wyraźnie zaznaczone.

Twoje uwagi, linki, własne artykuły lub wiadomości prześlij na adres:

webmaster@reunion68.com