Why do children with autism struggle to sleep?

Why do children with autism struggle to sleep?

ILANIT CHERNICK

New research study from BGU’s National Autism Research Center of Israel finds brain waves of children with autism are shallower

Studies have shown that some 48% of children on the autism spectrum have sleep disorders or disturbances.

A new research study from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev’s National Autism Research Center of Israel has found that brain waves of children with autism are shallower, particularly during the first part of the night, which indicates why they have difficulty falling into a deep, rejuvenating sleep.

Not only do they have a hard time falling asleep, but this large percentage also wake up frequently in the middle of the night, and wake up early in the morning.

Previous studies have shown that because of the sleep disturbance, severe challenges are created for the children and their families. Determining the causes that create these sleep disturbances is a first critical step in finding out how to mitigate them.

A team led by Prof. Ilan Dinstein, head of the National Autism Research Center of Israel and a member of BGU’s Department of Psychology, examined the brain activity of 29 children with autism and compared them to 23 children without autism.

The children’s brain activity was recorded as they slept during an entire night in the Sleep Lab at Soroka University Medical Center, managed by Prof. Ariel Tarasiuk.

According to the researchers, normal sleep starts with periods of deep sleep that are characterized by high amplitude slow brain waves.

“The recordings revealed that the brain waves of children with autism are, on average, 25% weaker (shallower) than those of typically developing children, indicating that they have trouble entering deep sleep, which is the most critical aspect of achieving a restful and rejuvenating sleep experience,” the study found.

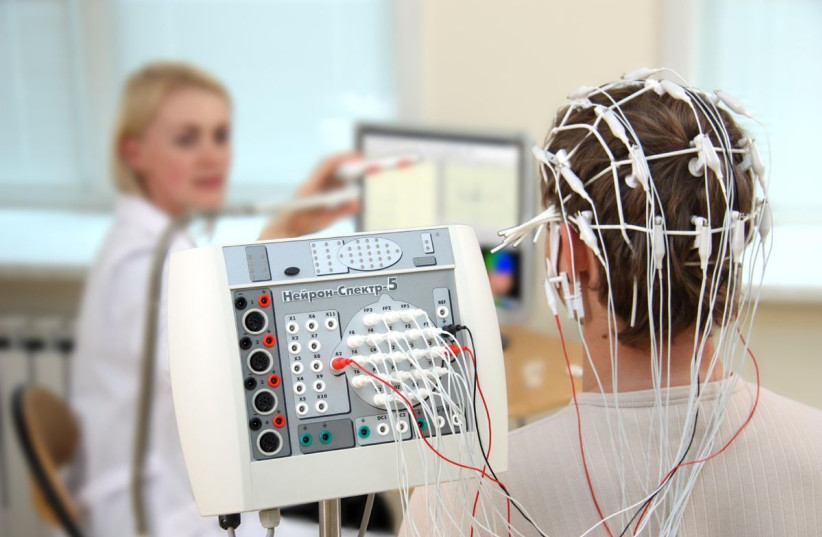

Speaking to The Jerusalem Post on Wednesday, Dinstein that the importance of this study is that “this EEG [Electroencephalography] measure tells us something about the mechanism of why the children are having trouble sleeping.”

An EEG is an electrophysiological monitoring method to record electrical activity of the brain.

“Finding the solutions that will help these children sleep better will require more research that we are starting to carry out this year,” he explained. “Potential alternatives include increased physical exercise, behavioral interventions that regulate sleep habits, and pharmacological interventions.

“All of these options need to be tested carefully,” Dinstein said.

He highlighted that deep sleep is a complicated state that is governed by a variety of hormones and other factors.

“Imbalances in any of these factors could create a situation where some of the children with autism do not fall into deep sleep,” Dinstein told the Post. “Nevertheless, we do not have a handle or measure for identifying a sub-group of children with a particular type of sleep difficulty. “This is important, because these children will likely need a specific solution – one that we have yet to identify,” he stressed.

Dinstein went on to explain that it appears that children with autism, and especially those whose parents reported serious sleep issues, “do not tire themselves out enough during the day, do not develop enough pressure to sleep, and do not sleep as deeply,” adding that they also found a clear relationship between “the severity of sleep disturbances as reported by the parents and the reduction in sleep depth.

“Children with more serious sleep issues showed brain activity that indicated more shallow and superficial sleep.” he added.

With the team now identifying the potential physiology underlying these sleep difficulties, they are planning several follow-up studies to discover ways to generate deeper sleep and larger brain waves, from increasing physical activities during the day to behavioral therapies, and pharmacological alternatives such as medical cannabis.

The research was supported by the Simmons Foundation Autism Research Initiative and was published recently in Sleep.